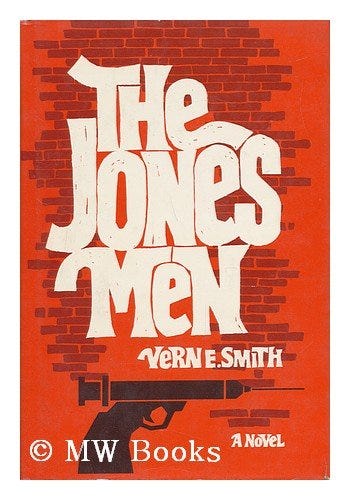

A few years back, I reviewed the reissue of journalist and novelist Vern E. Smith’s 1974 novel The Jones Men for American Book Review. Smith worked for various news outlets including Newsweek. Recently, he published his new novel Ghost Skins, which won an Outstanding Book Award at this year’s National Association of Black Journalists Convention Authors Showcase. I was able to read Ghost Skins a few weeks ago, and I reached out to Smith to see if he might be interested in answering some questions about his latest novel. He agreed, and below you will find my interview with Smith. You can purchase Ghost Skins on his website.

IR: You are a journalist, serving as the Atlanta bureau chief for Newsweek and covering the Atlanta Child Murders in 1980, among other stories. How did your training as a journalist impact your fiction writing, specifically for novels such as The Jones Men and your latest Ghost Skins?

VS: Journalism has a strict set of rules. Everything you publish must be sourced and factual. The writing must serve the reporting. Writing fiction for me is like improvisational word play. I’m riffing on the language in depicting a character’s action, trying the right combination of words that create a harmonic “sound” that is also visual for a reader, a kind of prose-poetry. For example, in the opening chapter of The Jones Men, there is a moment when the two main characters are striding down a hallway in a funeral home, past a group of elderly women, and it includes two short sentences: “The hallway reeked of death. The women wept.” Not sure where it came from, but it “sounded’” right.

I approach an idea for a novel in the same way as I do a news story, researching the subject until I understand the world I want to write about. In the case of The Jones Men, the novel grew out of a piece I reported for Newsweek called “Detroit’s Heroin Subculture,” in which I first used the term “jones men” to describe a new kind of urban gangster. I was approached by a publisher and made a deal to write a novel set in that world.

My earliest writing as a young teenager was fiction, inspired by the sports and adventure novels I was reading. At San Francisco State University, I studied Journalism and script writing as a Radio-TV-Film minor. The first piece of fiction I ever sold was a story for a TV detective show called Mannix when I was a young newspaper reporter living in California. The story was never produced but earned me the biggest check I’d ever seen as a writer at that point. I think being a journalist taught me how to inject immediacy into a story, and the need to get on with it.

IR: Can you comment on the inspiration for Ghost Skins and why you chose to self-publish it? You told me, at one point, that with the current atmosphere of book bannings, you were concerned with a mainstream publisher being wary of the topic coming from you. Can you discuss this some?

VS: There were a couple of things I had been noodling that came together in this story. I’d always liked the idea of writing a novel about a mysterious, international criminal who thought he couldn’t be captured ever since I read A Coffin for Dimitrios by the British spy novelist Eric Ambler. Then I later came across a tiny FBI bulletin sent out to law enforcement agencies warning of reports of a new phenomenon: Closeted white supremacists who hid their true leanings to infiltrate police and military agencies to carry out acts of violence against targeted American citizens. They called themselves “ghost skins,” according to the bulletin. I was also aware that America’s historic racial divide had been a target for exploitation by foreign adversaries since the Cold War. Once I had my main character and setting, I was off and running. After the events of January 6, 2021, when so many former and current police officers and military personnel were implicated in the attack on the U.S. Capitol, I knew Ghost Skins would be incredibly timely.

I didn’t start out with the idea of independently publishing the book, but as Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor used to say, “new occasions teach new duties.” By the time I finished the manuscript, I felt there wasn’t enough time to shop it in the traditional way if I wanted it to come out this year, and the current political frenzy around the banning of certain books made me think that there might be another pre-publication battle. So, I hired a copy editor and a cover designer and went for broke. I’m a National Magazine Award winner, and an Edgar Award nominee for The Jones Men, which was a New York Times Recommended Book when it was first published. I think as readers learn about Ghost Skins, they’ll be inclined to give it a read or a listen in the case of the audio book

IR: Ghost Skins deals with the intersections of a myriad of topics from systemic racism, foreign interference in our political system, and far-right extremist groups. We know that under Barack Obama extremist groups within the United States reached an all-time high. Since then, the numbers have been declining, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC). In their 2022 report, the SPLC stated that “Rather than demonstrating a decline in the power of the far right, the dropping numbers of organized hate and anti-government groups suggest that the extremist ideas that mobilize them now operate more openly in the political mainstream.” There is no public extremism in Ghost Skins from the “political mainstream,” but how does the novel fit within these conversations about the “normalizing” of extremist rhetoric in politics?

VS: The open embrace of extremist groups by high-ranking political leaders comes as Homeland Security experts have said these groups represent the most persistent and lethal terrorism-related threat facing America today, replacing foreign groups like al-Qaeda. This mainstreaming of white nationalism is one of the most frightening aspects of modern American life. There is a Southern Congressman in Ghost Skins who uses a militia group as his security force and most of them turn up on Homeland Security Watch Lists as “RMVES” — Racially Motivated Violent Extremists. My novel is less a cautionary tale and more a reflection of the world we live in now.

IR: While Ghost Skins has a tight, regional focus on Chicago, with a detour to New Jersey, it really is a novel dealing with global extremism. We see this with the character of Oswald Eyler and the main antagonist in the novel. With what we have seen in Europe, specifically in Germany recently with the first election of a far-right party in Germany since 1945 and with Viktor Orbán in Hungary and with Giorgia Meloni in Italy and other examples, how do you see your novel within a global rise in far-right, anti-government, anti-democratic extremism?

VS: It struck me during the research how connected the rise in European right-wing extremism is to what is happening in America today. Homeland Security sources have reported individual Americans “reaching out to foreign groups, and connecting over common ideology, tactics, and training.” It’s a reminder that America’s “Jim Crow” laws, which codified racial segregation for a century, were inspiration for what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the Nazi regime’s vicious anti-Jewish legislation of the 1930s. Meanwhile, as the 2024 American election approaches, the extreme racist rhetoric on the right seems to increase daily.

IR: The narrative spark in Ghost Skins takes place on the opening pages with a white, Chicago police officer murdering Big Ed Riley, a defensive star for the Chicago Bears. Riley does a lot in the community, and they love him. Why did you decide to have Riley’s murder as the impetus setting the narrative in motion?

VS: The tension between Black communities and the mostly white police departments that patrol them has been the flashpoint for upheaval since the 1960s. I wanted to introduce the reader right away to Big Ed, a young, successful Black man, loved by family and the community and suddenly his death after a late-night encounter with a police officer rocks Chicago. The story starts as a mystery because the reader doesn’t witness what occurs after the initial stop. When Dawes, the Chicago PD homicide detective gets the case just as he’s ending his shift, he’s confronted with a horrific scene that makes no sense. The more he peels back the onion in trying to understand what transpired and why, the more the story twists and turns and morphs into something more complex and frightening. In trying to create a peak reading experience, I’m mixing genres in this novel. There are elements of mystery, suspense, action, espionage, and family drama, because the protagonist, Dawes, is also a husband and father with a teenage son. In mixing genres, you generate more plot beats, and the story keep unfolding in surprising ways.

IR: You are from Natchez, Mississippi, and you dedicate Ghost Skins to your uncle Vernon and Richard Wright, pointing out the migration from Mississippi to Illinois. Can you speak some to that dedication and also to other writers, along with Wright, that have inspired you? I ask the latter part of that question because I see you in the lineage of Chester Himes, Iceberg Slim, Donald Goines, Walter Mosley, and others.

VS: I decided to set the story in Chicago because I felt it needed to take place in a Midwest locale. I’ve always had an affinity for Chicago before I ever visited the city having so many family members and friends who had relocated there over the years. My Aunt Mary Louise Mingee, my father’s youngest sister, taught for years in the Chicago public schools. I name a character after her in Ghost Skins. I have a younger cousin who is a former Chicago police officer, and two even younger ones who teach high school Algebra and Math. My namesake in the dedication, Vernon Lee Smith, was my father’s youngest brother. He settled in Chicago after he was discharged from the Army after World War II. He only returned to Natchez once, when I was very young, but it left a lasting impression. I later reunited with Uncle Vernon when I was on assignment in Chicago for Newsweek.

Growing up, I’d heard about Richard Wright before I read his work because he was listed as a relative on our family tree on my father’s side. He only has a very short mention of Natchez in his autobiography Black Boy, but I visit the plaque on the river bluffs that honor him every time I’m in Natchez. Of course I read James Baldwin. I have a writer friend who says he wanted to be James Baldwin when he started out. I met Baldwin once when he was working on a book about the Atlanta Child Murders and a friend brought him by my house to debrief me about covering the case. As he sipped Johnny Walker Red Scotch Whiskey over ice, I asked him who he wrote for and he said, “For whom soever will.”

Well-told stories transcend race; they are about the human condition which can bring about empathy. It’s one of the main reasons people want to ban certain books. I came of age during the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s, so I was also influenced by playwrights like Ed Bullins, Douglas Turner Ward, poets like Amiri Baraka and Sonia Sanchez.

I’d be proud to be included on a list with the likes of Himes, Iceberg Slim, Walter Mosley and Donald Goines, all of whom I’ve read and studied. One of the first books that captured me with its vivid writing was Manchild in the Promised Land, by Claude Brown. It’s a non-fiction account of growing up in New York. The writer Richard Price put me on his list of favorite writers of detective fiction in a New York Times article, but he called a book like The Jones Men “crime-centric fiction,” a description I think fits Ghost Skins: A roller coaster of a thriller that makes you think about a lot of things.

Thanks for the opportunity to talk about the book.