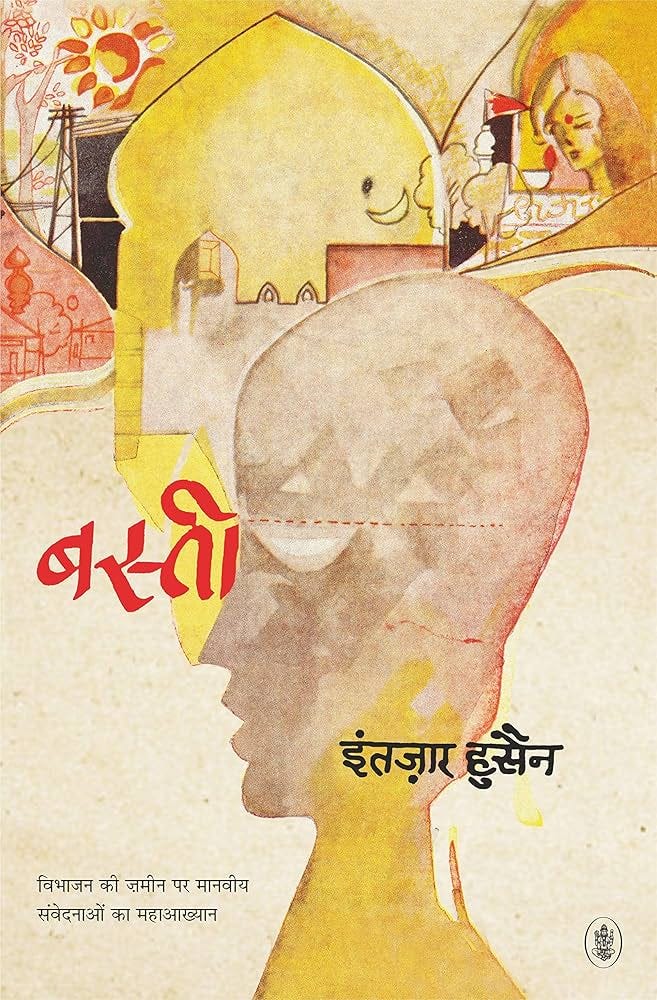

In my last post, I wrote about the spreading disease and the creation of monsters, specifically the ways that virulent ideologies spread throughout a society. I’ve thought about this a lot over the past few years, and it is a theme that keeps coming up, again and again, in novels I’ve been reading, specifically two novels I am teaching in my Reverberations of World War II class: Pakistani writer Intizar Husain’s Basti and Japanese writer Yuasa Katsuei’s Kannani. Each of these novels deal with the ways that we repress our own histories and the ways that societies directly spread virulent ideas that harm countless individuals.

Husain’s Basti reminds me, in many ways, of Magda Szabo’s Katalin Street, specifically in the ways that it addresses memory and the ways we talk about our own personal experiences and our cultural experiences. The novel moves back and forth through time, ostensibly set it 1971 during the Indo-Pakistan War and going backwards to pre-partition India before 1947 and even referencing the Indian Rebellion against the British East India Company in 1957.

Zakir is the protagonist of Basti and the novel follows him through the events of 1971 and back into his past. He teaches history at a school in Lahore, and when one of the demonstrations breaks out, he is working on his lecture for the next day. As he sits at his desk and thinks about his students, he contemplates, “Today I somehow managed to finish the Mughal period. Teaching history is a bore. And studying history?” Zakir the relates the “absurd questions” his students ask him, not about events and how they impact the students’ lives but about whether or not all of the male Mughals were “stepbrothers.”

Zakir’s thoughts here remind me so much of my own son. For the past few years, he has been obsessed with the presidents of the United States. During that time, he memorized every presisdent and their terms, along with their vice presidents. He can even recite every president, in order, in about 30–40 seconds. Yet, when he first started learning about the presidents, he asked similar questions about their lives. He did not care anything about their policies or what they actually did. He started at a base level. However, over the past few years, he has started to become more interested in their policies and positions, asking specifics about each president.

Zakir does not give the boys space to move beyond the “absurd questions.” Instead, he views history as a bore, both in studying it and teaching it. This boredom arises, in part, from the ways that history impacts his present. As a child, one of Zakir’s friends was Surendar. Zakir is Muslim and Surendar is Hindu, and the tensions exasperated during Partition in 1947 provide a foundation for the text, and that event causes the friends to separate and go their different ways, Zakir to Lahore in Pakistan and Surendar to Delhi in India. The last time they see each other, they walk out of Khirki Bazaar and come to a road that comes out “in the Hindu neighborhoods” and connects to “a lane that went to the Muslim neighborhoods.” Here, at the intersection of the roads, “both hesitated, looked at each other in silence, and seit out on their different roads —” The quote is open, indicating their distance and separation, but not the overall conclusion of their connection.

The cultural moment of 1971, coupled with Partition and other historical moments, causes Zakir to really question his role as a history teacher and the importance of history. When the boys ask him, “Among the Mughals, were all the brothers stepbrothers?” he chastises them because he sees their question as “meaningless to distinguish full brothers from stepbrothers. Cain and Abel weren’t stepbrothers.” His thoughts point to the ruptures caused by the Partition of India and the fork in the road that him and Surendar took to their respective communities. Zakir continues to view his profession as boring, and when it comes to studying history, he experiences discomfort.

For Zakir, “[o]ther people’s history can be read comfortably, the way a novel can be read comfortably.” However, when it comes to one’s own history, individuals run from hit. Zakir says, “I’m on the run from my own history, and catching my breath in the present. Escapist. But the merciless present pushes us back again toward our history.” Confronting our own history, whether personal or societal, causes discomfort. It is much easier for us to study the history of others and to look at them either with disdain or admiration for their actions.

For Zakir, it would be easier to look at the United States’ actions during World War II instead of looking at the ways that Partition impacted his life and the lives of those he loves. For us in the United States, it becomes easier for us to look at Nazi Germany and condemn them for the murder of millions of Jews, Roma, disabled individuals, and others instead of looking at our complicity in their atrocities and the atrocities we committed against Indigenous individuals, African Americans, immigrants, and more. As Lillian Smith wrote during World War II,

I think sometimes that we hate the Nazis even more than we otherwise would because we know that their conscience has hurt so little while ours has ached and pained us for 300 years! And nowhere has it hurt us more than in the Deep South where we have lynched, burned and segregated human beings simply because their skin was darker than ours. And nowhere is hatred of the German Nazi worse than in the Deep South . . .

Smith’s word epitomize Zakir’s thoughts. She argues that we condemn, and rightfully so, Nazi Germany while ignoring our own faults because in condeming them it makes us feel better about ourselves. It makes us feel “comfortable” because we do not feel the past pushing on us in the present.

We do not need to feel comfortable when we confront history. No matter how horrendous history was, we cannot sugar coat it and mythologize it, crafting stories to make ourselves feel better about ourselves. When we do this, we repeat, again and again and again, the atrocities of the past and continue to perpetuate the virulent ideologies we condemn. As Frederick Douglass wrote, “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future.”

Next post I will continue this discussion by looking at Yuasa Katsuei’s Kannani. Until then, what are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.