Over the past few weeks, I’ve been reading multiple books set in Marseille. Specifically, I have read two novels detailing the movement of refugees during World War II to the port city in hopes of escaping the Nazi advance. Before leaving for Marseille, I read Julie Orringer’s The Flight Portfolio, a fictionalized account of Varian Frye’s work the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC) in Marseille during the war. In her review of Orringer’s novel, Cynthia Ozick asks us to think about the “war between history and imagination” that Orringer creates within the novel between the real life Frye and his fictive depiction in The Flight Portfolio. This “war” exists in countless classical texts, as Ozick points out, but in Orringer’s case the war between reality and fiction has real consequences because, as Ozcik writes, “we do have a stake in whatever touches on the historical integrity of the Holocaust, now increasingly denied, diminished, demoted, misapplied, perverted, derided; or else utterly erased.”

Ozick’s points about the tensions between the historical fact and the fictive imagination make me think about her novel The Messiah of Stockholm and the use of Polish writer Bruno Schulz within the narrative. While Schulz appears in the minds of the characters within Ozick’s novel, he serves as the fulcrum for Lars Andemening dealing with his own identity and the aftermath of the Holocaust. Andemening believes he is Schulz’s son and that he must resuscitate Schulz’s literary prestige. Schulz looms over the novel as a specter haunting Andemening’s search for himself.

Upon returning from France, I picked up Anna Seghers’ Transit (1944), a novel that in many ways reminds me of The Messiah of Stockholm and that details, during the events of the war, the refugee crisis in Marseille in the early 1940s. Peter Conrad notes that Seghers’ novel draws upon her own experiences, first being arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 for her communist sympathies then her journey to Marseille and ultimately Mexico in 1941, fleeing the Nazi march across France. Conrad continues by pointing out the mythic nature of Transit, the flipping of mythology and the overall sense of desperation among the narrator and refugees within the novel. This feeling runs counter to the narrator’s observations that life maintains, it continues daily as if the war encroaching towards the Mediterranean doesn’t affect everyone in the port city. Some, like the Billets, carry on with their lives.

The novel opens with the unnamed narrator, who escaped from a German concentration camp, meeting up with Paul, another concentration camp survivor, and Paul asking the narrator to deliver a letter to the author Weidel. The narrator finds out that Weidel committed suicide, and he takes Weidel’s belongings with him to Marseille, passing himself off as the famous author in the hopes of securing the necessary papers for transit out of Europe. Initially, the narrator wants to stay in Marseille, but as time progresses, he determines that he must leave. The narrator’s masking as Weidel and the ways that fiction and reality become intermingled is what reminds me of Ozcik’s and Orringer’s novels. The narrator completely embodies Weidel.

Along with this, I am also drawn to the discussions, in each of these novels, about the role of art as a form of resistance and mechanism for coping with trauma. Varian Frye, through his work, saved more that 2,000 people from the Holocaust, and the ERC focused on individuals they deemed artistically and intellectually valuable. This serves as one of the main tensions within Orringer’s novel, the question of who is worthy of saving and who must exist under the constant threat of getting shipped away in a rail car. As Ozcik notes in her review, “[The novel] uncovers a moral flaw inherent in the primary aim of the Emergency Rescue Committee, premised on the principle of Orwell’s Animal Farm. World-famous Chagall — yes. A pious 15-year-old in an obscure town in the remote Carpathians, who will one day be known as Elie Wiesel — no.”

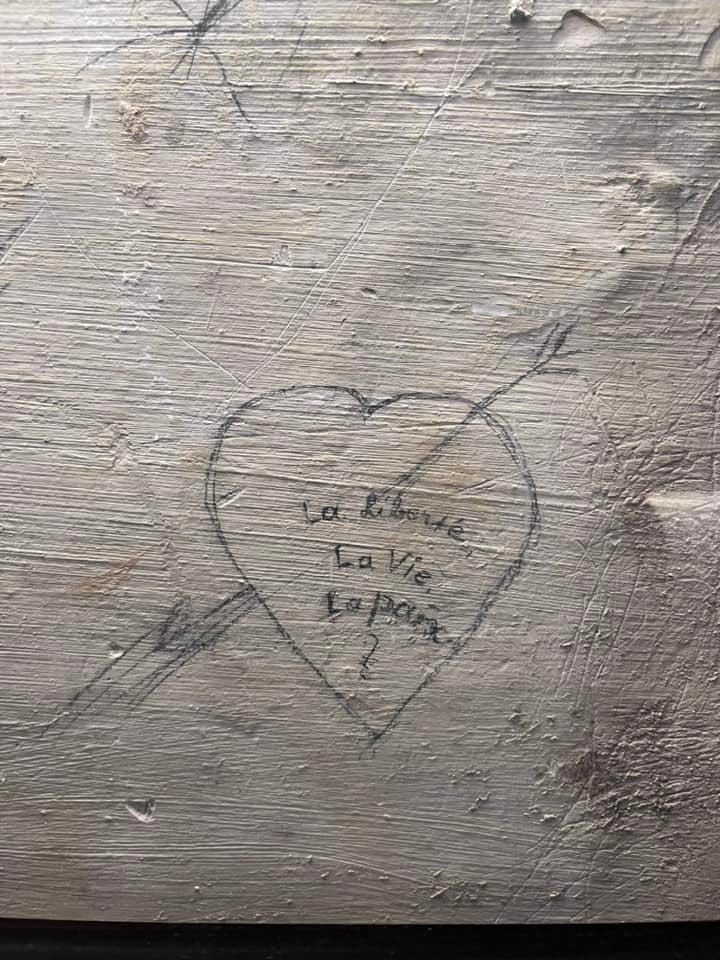

Art exists at the center of each of the texts I’ve mentioned so far, and as I toured Camps des Milles, an interment camp near Aix en Provence, I was reminded of the role and power of art as resistance. The Germans interned countless artists and intellectuals such as Lion Feuchtwanger, Max Ernst, Otto Fritz Meyerhof, and more at Camps des Milles, and the tour highlighted the role of art within the camp as a mode of resistance. Art covers the walls next to the kilns where the internees slept. Polish artist Julius Mohr painted flowers on the walls, and other internees drew various things on the walls such as a heart inscribed with “La liberte, La vie, La paix.”

The art remains. The art that those intered at Camps des Mille created remains. The art and intellectual achievements of those such as Marc Chagall, Hannah Arendt, and Max Ernst whom Frye helped to save from the Nazis remains. They will remain forever, etched into the walls of our psyches for us to call upon in the face of ever increasing fascism within our midsts. They stand as a testament of resistance and as a rallying cry for those of us in the current moment.

Near the end of Transit, the narrator says that if the Nazis find him they will shoot him. However, he will remain. He writes, “Even if they were to shoot me, they’d never be able to eradicate me. I feel I know this country [France], its people, its hills and mountains, its peaces and its grapes too well. If you bleen to death on familiar soil, something of you will continue to grow like the sprouts that come up after bushes and trees have been cut down.” The Nazis can kill, but they cannot eradicate. The seeds will take root in the soil and propagate, growing anew to resist the onslaught of fascism.

The narrator’s assertion of continued resistance serves as a coda to a scene earlier in the novel where the narrator describes hiding from a German convoy. He overhears the commanders barking orders, and even though he fled from Germany he has the desire to stand at attention, but he does not. He thinks about the disciplined soldiers falling in line with bloodshed all around them, and the narrator draws attention to their acquiescence to the terror that lies in their wake. He states, “And yet thrumming like an undertone in these commands was something terribly obvious, insidiously obvious: Don’t complain that your world is about to perish. You haven’t defended it, and you’ve allowed it to be destroyed! So don’t give us any crap now! Just make it quick; let us take charge!” The narrator points out that we must fight before it becomes to late, because if we don’t, then the world as we know it will perish.

There’s a lot within these novels that warrants discussion. Each causes us to think about profound questions and our own roles within society, specifically our resistance to fascism and tyranny. What are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham