Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis covers a large period of time following the Islamic Revolution in Iran during the later 1970s. While the memoir traces Satrapi’s journey as her and her family navigate the authoritarianism that followed the revolution, her own experiences and insight provide us with insights into the psychological impacts of authoritarianism and the ways that it works to essentially squash any form of self-thought and protest. Satrapi highlights the weight of authoritarianism throughout Persepolis, through her parents sending her to Austria to escape the oppressive regime to her live back in Iran after school. While I cannot explore each instance where Satrapi exposes the ways that authoritarianism and religious fanaticism oppress individuals, I will focus on a few specific instances in Persepolis that provide a good overview and showcase the importance of not becoming complacent in the face of systems that seek to control you.

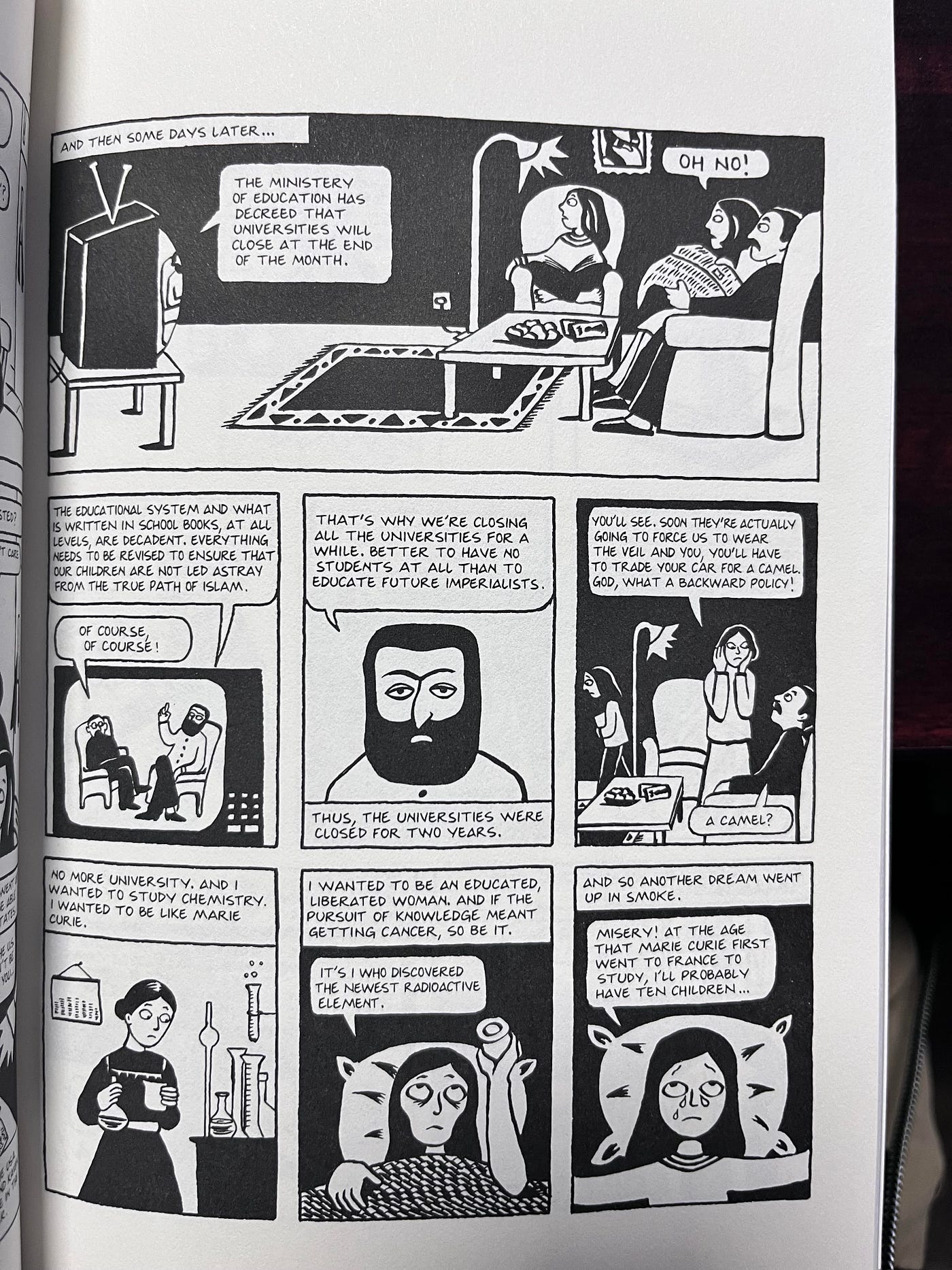

Following the revolution, Satrapi and her parents sit and watch the news as what appears to be a government official talks about education. He tells the reporter, “The Ministry of Education has decreed that universities will close at the end of the month.” The official continues by telling everyone that the system and the textbooks, “at all levels, are decadent,” leading children “astray from the true path of Islam.” To counter this, the government decided to close universities for a few year so as not to produce and “educate future imperialists.” Under the guise of “education” and “protecting the children,” the government sought to squash any form of dissent, eradicating it at the root. To achieve this, they worked to filter the information that students received.

Authoritarians and fascists always seek to control education because in this manner they can construct the narrative of the nation. As Jason Stanley points out, “Erasing history helps authoritarians because doing so allows them to misrepresent a single story, a single perspective.” We’ve seen this in multiple iterations from the United Daughters of the Confederacy to Stalin’s Russia to Nazi Germany to Mao Ze Deng’s China. When a government seeks to craft a nationalistic narrative of the nation, it also comes come with “more general restrictions on knowledge,” as Stanley notes, “and by attempts to push mythic representations in place of that knowledge.” This is what happened in Iran following the revolution, and this push also led to the oppression of female students through the wearing of the veil. Satrapi’s mother, upon hearing the official, proclaims, “You’ll see. Soon they’re actually going to force us to wear the veil.”

The forcing of women to wear the veil, the fear of professors to speak out, the suppression of knowledge and information, as well as other oppressive measures, cause individuals to focus on things that will bring harm to themselves or those they love instead of focusing on their own freedom and thoughts. Talking about the fear that seeped into the psyche of the populace following the fact that “the government had imprisoned and executed so many high-school and college students” leading to individuals not talking about politics, Satrapi details the small, discreet acts of resistance but also the ways that authoritarianism causes individuals to live in so much fear that they cannot function.

After highlighting that she spect a day in front of the committee for the color of her socks, Satrapi provides three panels that detail the psychological toll of authoritarianism. In the first, we see Satrapi walking towards the right side of the panel as she thinks about her clothing and whether it meets the standards set by the regime. She asks, “Are my trousers long enough? Is my veil in place? Can my makeup be seen? Are they going to whip me?” Satrapi focuses on these things, these insignificant things, because they are the things that could get her whipped or killed. One need only look at Masha Amini who died in 2022 after the Morality Police beat her for not wearing her hijab “properly.”

While Satrapi ponders her clothing and appearance, she cannot ask herself other questions. The second panel shows Satrapi from behind, walking away from the reader and the questions that one would hope to ask in her situation. As she walks away, she asks herself,” “Where is my freedom of thought? Where is my freedom of speech? My life, is it livable? What’s going on the in the political prisons?” Instead of focusing on these important questions, questions that impact her and those around her, she must ponder he appearance and whether or not it offends men and tempts them.

Satrapi concludes this sequence by addressing us as readers directly. She stares out towards us and states, “It’s only natural! When we’re afriad, we lose all sense of analysis and relection. Our fear paralyzes us. Besides, fear has always been the driving force behind all dictator’s repression. Showing your hair or putting on makeup logically became acts of rebellion.” Fear does paralyze us. It causes us to cower. It sparks our fight or flight response, and since we think about our own wellbeing and the wellbeing of those we care about, we usually choose flight. Or, if the oppression doesn’t appear to impact us, we choose to ignore it, to willfully remain oblivious and turn our back on others in our community.

Many still look at a memoir like Satrapi’s Persepolis and say, “That could never happen here.” They look at Iran and other authoritarian countries through the mythological gaze of American exceptionalism. They delude themselves into the idea that democracy cannot succumb to authoritarianism or fascism. They hold these views as they cheer on deportations of individuals without due process. They hold these views as they cheer on deportations of students who exercise their right to free speech. They hold these views as they cheer on the dismantling of education, of social services, of services meant to keep us healthy. They hold these views as they cheer on the expansion of executive power. They hold these views because they see themselves as immune, as individuals who will not face any oppression.

When I think about all of this, I keep thinking about something that Salman Rushdie says in Knife. Addressing attacks on freedom of speech and freedom of expression, notably after the fatwa against him for The Satanic Verses, Rushdie writes, “If you are afraid of the consequences of what you say, then you are not free.” Satrapi highlights this. She is not free because she cannot say what she wants to say. She cannot express herself. Instead, she must think about miniscule things that could get her in trouble. We see similar things today, here, with universities, news organizations, and other entities who fear the repurcussions if they say anything. The First Amendment, meant to protect speech, has been under attack, and the continued attacks mean that individuals become fearful of what they say, thus making them “not free.”

Authoritarianism thrives on fear to maintain control. When we become fearful, we give in to authoritarianism and we succumb to that fear, allowing the authoritarian to trample us underfoot. Nothing scares authoritarians more than the truth, more than knowledge, more that the voices of the people who stand up and speak out.

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.