Elizabeth Colomba and Aurélie Levy’s Queenie: Godmother of Harlem tells the story of Stephanie St. Clair, “a racketeer and a bootlegger” who became infamous in Harlem during the 1930s. Born and raised on a plantation in Martinique, a French colony, St. Clair left the island in 1912 for the United States, and she made a name for herself, rising above the poverty and racism and she endured, becoming “the ruthless queen of Harlem’s mafia, and a fierce defender of the Black community.” Queenie details St. Clair’s fight to maintain her territory and save herself as Italian mobsters seek to acquire her assets and position. She counters these attacks through the cultivation of her image and through her support of the Black community.

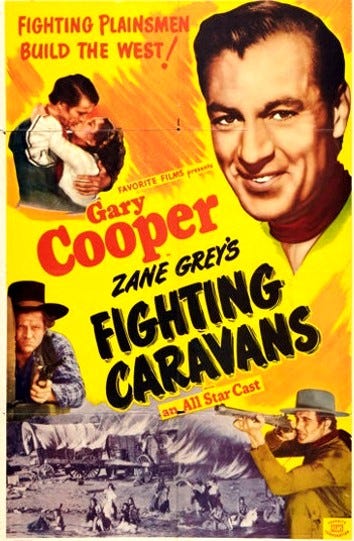

I could do a whole post on Queenie, but instead of focusing on everything in Colomba and Levy’s graphic narrative, I want to focus on one scene where St. Clair, along with her righthand man Bumpy, meet with Harris to discuss ways to eliminate Dutch Schultz from the equation. The meeting takes place in a movie theater during a screening of Gary Cooper and Lili Domita’s 1931 western Fighting Caravans, a film based on Zane Grey’s 1929 novel of the same name. In the film, Cooper plays Clint Belmet, a frontier scout who accompanies a wagon train out west, encountering attacks from Indigenous individuals and smugglers along the way. The film, of course, is one of many westerns from the period, but it’s important that St. Clair and Bumpy choose this film for the meeting with Harris because it sparks a powerful conversation between the three about representation and the psychosis of white supremacy.

When Harris comes into the theater, he sits down in front of St. Clair and Bumpy and asks, “You like this cowboy shit?” Bumpy tells him, “It’s a reminder. When I was a kid, I rooted for the cowboy.” Most kids played imaginary games of cowboys fending off the frontier from “savages,” placing themselves within the hero’s shoes, protecting property and women from the “vicious” attacks of the “uncivilized Indians.” Thus, they rooted for the cowboy. However, as Bumpy notes, his thoughts changed, specifically because, as he tells Harris, “America happened! I grew up and realized I was the Indian all along.” An asterisx appears after Bumpy’s comment here, causing the reader to turn to the end of the book and look at the note for that page; however, no note appears.

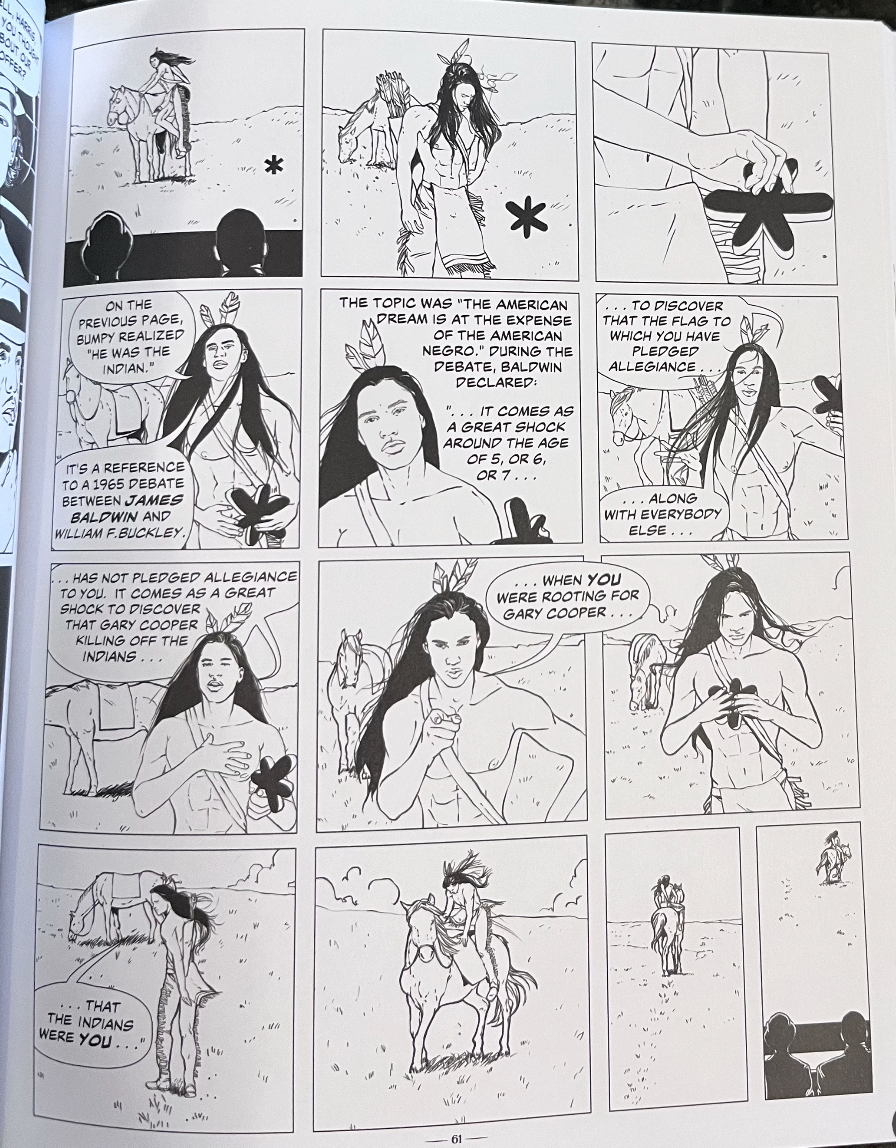

The rest of the page shows St. Clair talking to Harris about the proposed deal to get rid of Shultz, and after the conversation, Harris leaves the darkened theater. As Harris stands up and walks out, we see the screen depicting a scene where a group of Indigenous men attack a wagon train, riding around the wagons with arrows poised to fly from their bows. This image leads us into the screen where we encounter a 10 panel page where an Indigenous man dismounts his horse and picks up the floating asterisk above Bumpy’s hand. He approaches it, picks it up, and then begins to speak.

Holding the asterisk, the man looks at the reader and says, “On the previous page, Bumpy realized ‘he was the Indian.’ It’s a reference to a 1965 debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley.” The Baldwin/Buckley debate took place at Cambridge University’s Union Hall in 1965. It was a debate on race relations in America during the period between an African American writer and intellectual and a leading conservative intellectual. The Indigenous man tells us, “The topic was ‘The American Dream is at the expense of the Negro.’” During his opening comments, Baldwin proclaimed, “It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, or 6, or 7, to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you.” Once the man finishes quoting Baldwin, he turn back to his horse, mounts it, then rides off into the distance. The final panel shows the man riding on screen as we see the back of St. Clair’s and Bumpy’s heads gazing at him.

Baldwin’s comments speak to the realization of Black children, at a young age, experiencing mass media that depicts whites as the heroes and the norm and anyone else as “savage,” “uncivilized,” or “dirty” and in need of elimination. While Bumpy initially thought of himself as the cowboy saving the wagon train and protecting white women, he realizes that Cooper and the other cowboys on screen don’t represent him. They are not him. They are white. Cooper’s “killing off the Indians” causes Bumpy to realize he is one of the “Indians.” He is the Other that the white Cooper fears and seeks to keep at bay. This, by extension, makes him think about the nation, a nation that treats him negatively because of the color of his skin, a country that, even though he was born in it, “has not,” as Baldwin continues, “in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for” him, St. Clair, or Harris.

This realization has a psychological impact, causing the indiviual to view themselves as inferior and leading them to lose trust in their nation and “countrymen.” Baldwin details all of the micro and macro aggressions he, as a Black man, endured from law enforcement, bank managers, landlords, and more. However, as he tells his audience, these are not the most powerful effects “of the mill you’ve been through.” Baldwin states that the most serious effect occurs “by that time that you’ve begun to see it happening, in your daughter or your son, or your niece or your nephew,” the psychological pounding down of an individual, at such an early age that leads them to believe in their inferiority because the media and culture proclaim it to them.

This moment in Queenie, while small, is powerful because through the movement into the screen to have the Indigenous man explain Bumpy’s words Colomba and Levy highlight the impact, visually, of mass media on the psyche of individuals and the ways that these images reinforce ideas of inferiority, even when a person of color roots for say Cooper of Tarzan to defeat the “savages.” I’ve written about this in more detail a few years ago when I wrote about John Ridley calling HBO Max to add context to films such as Gone with the Wind.

What are your thoughts? Let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.