Shut up, put one in the air

’Cause when I get it, I get it out everywhere

Serving and slinging, I’m not sitting scared

Elites don’t fight fair, I got no time to care

40 years of Reaganomics, n****, this what we get

N****, it is what it is, the world in service and shit

Deliver food we spit in, can’t even cook for they kids

Yo, my n**** stay flipping gear in a pinch — Soul Glo “Driponomics”

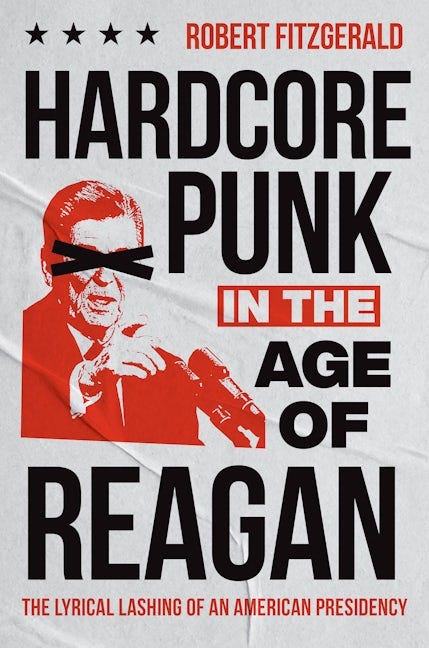

When I initially saw Robert Fitzgerald post about the upcoming release of his new book Hardcore Punk in the Age of Reagan: The Lyrical Lashing of an American Presidency, I knew I wanted to read it because I wanted to learn more about the history of punk both as a musical movement but also as a political force, that, as Fitzgerald points out, are important historical and contemporaneous documents that help us understand “grassroots oppositional forces” to political positions that harm individuals. Fitgerald adds that “[w]e need to see their lyrics for what they are: primary source documents of a key cultural moment in the history of the United States and a first-responder, artist-based reaction to the Reagan Revolution.”

Punks, like any artistic movement, provide commentary on the world and serve, in many ways, as prophets preaching to the masses about the downfalls of political positions and systems of power. The masses dismiss prophets, but they serve as one of the last lines of defense against authoritarianism, theocracy, fascism, etc. In 1980, many saw Reagan’s election as a danger to the nation and the world, especially his positions of race, interventionists tendencies in Central and South America, deregulation of corporations, law and order, and more. Punks, who faced down the new administration’s policies and positions, spoke back against Reagan and his acolytes, and they created a “musically inspired countermovement,” as Fitzgerald put it, “that is as canonical in the American songbook as the folk and rock protest music that preceded it” from Woody Guthrie to Joan Baez to Nina Simone to Pete Seeger to Phil Ochs, and more.

Organized from Reagan’s entrance into the Oval Office in 1980 to his legacy and the election of Donald Trump in 2016, Hardcore Punk in the Age of Reagan breaks down the ways that punks, through their music and lyrics, responded to the myth of the American Dream, the post-Vietnam War milieu in relation to the military and military intervention across the globe, the fear of nuclear Armageddon, the rise of Christian fascism, the rhetoric of law and order, and the racist policies of mass incarceration and stripping of social services from millions of individuals. Fitzgerald constructs each chapter by beginning with a epigraphs from Reagan and punks, moving to historical context of the topic, then detailing, in various ways, the ways that punks responded to the policy or position. This framing allows Fitzgerald to present the “scholarly” aspects before pointing out the ways that punks, from a grassroots level, expressed the same disenchantment as other members of the nation’s populace.

Fitzgerald presents so much over the course of Hardcore Punk in the Age of Reagan, and at points it can feel like an endless list of bands, songs, and lyrics because so much gets thrown our way at once, like a forty-five second punk blitzkrieg. At first, Ifound this overwhelming because I would stop, after every section, and dig deeper into the bands and songs Fitzgerald discusses. As someone who came of age during the lull in punks confronting presidents (the mid to late 1990s), I knew, over the years, of some of these bands, but Fitzgerald introduced me to so many more, bands that spoke to their current moment during Reagan’s administration and continue to echo through the decades into the twentieth century, as prophets are wont to do.

While I could break down every topic that Fitzgerald presents in the book, I don’t want to do that because most individuals, even with a cursory knowledge of history, know the things and institutions that punks confronted during Reagan’s eight-year occupancy of the White House. For me, Fitzgerald’s incorporation of countless bands, from across the nation and the world, drew me in, specifically his focus, at times on the South. As a Southerner from North Louisiana, I never felt, except maybe in college, that we had a scene, a scene responding to anything. I know scenes existed in Arkansas, Louisiana, and elsewhere in the South, but I never knew them. Fitzgerald doesn’t detail all of these Southern scenes; in fact, he rarely, if at all, mentions Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, or Georgia. He focuses on Texas, notably Houston and Austin, North Carolina, and Virginia.

I’ve known about Texas’ M.D.C. for years, but Hardcore Punk in the Age of Reagan introduced me to bands such as Really Red and The Dicks. Their proximity to my hometown and their origins in the region where I called home for most of my life drew me to each of these bands. Listening to songs like Really Red’s “Teaching You the Fear,” which details the murders of Carl Hampton, José Campos Torres, and Fred Paez at the hands of Houston police, and The Dicks songs like “Anti-Klan (Part 1)” encapsulate so much about the intersections between the intersections of policing and race in the South, even during the 1970s and 1980s. Also, learning about the band AK-47, which only released one 7″ stood out because the lead singer, Tim Fleck (aka Tim Phlegm) was a journalist who covered the Houston police department and even sat in a press conference where the chief of police, without knowing Phlegm was the singer, said that the AK-47’s song “The Badge Means You Suck” needed to be addressed. The song relates the story of Milton Glover, a Black Vietnam veteran whom two Houston officers shot eight times when he was experiencing a mental episode. The cover, reminiscent of M.D.C.’s cover for Millions of Dead Cops, has the names of victims of police brutality in Houston.

I could spend a long time detailing everything that I took away from Hardcore Punk in the Age of Reagan, populating this post with countless videos and songs, but then I would create a bloated post akin to the bloated stadium rock that punk usurped. I’ll end by noting that throughout the book Fitzgerald navigates a vast amount of territory, working to cram as much as possible into a small book, just as a punk song crams so much into songs that last than thirty seconds. That means that Fitzgerald can, in no way, cover everything. The “Outro,” which moves forward from Reagan, going through punk responses to the presidents up to Trump in 2016 feels important but extremely truncated. Punk pushes back against authority, exposing the cracks like the biblical prophets, and calling upon us to pay attention. As D.O.A. frontman Joey Shithead said in 2016, “When lies and corruption rule the land, it’s been a time honored tradition that artists become one of the last lines of defense, that’s the tradition of folk, punk, and rap, we have to stand up against the racist, divisive bullshit that’s coming from the White House.”

Fitzgerald does a good job detailing a lot of the backlash to presidents and authority since Reagan, but this discussion feels lacking in so many areas, notably the rise of the Riot Grrrl scene during the late 1980s and early 1990s, notably with songs such as Bikini Kill’s “George Bush is a Pig” about Bush I or moving forward to Sleater-Kinney and their album One Beat, notably songs like “Far Away” and “Combat Rock” which directly speak to Bush II’s War on Terror. This doesn’t even include songs about patriarchy and misogyny such as Heavens to Betsy’s “Terrorist” or Bikini Kill’s “White Boy.”

Along with this, Fitzgerald does mention the ways that punk influenced the grunge scene, especially Nirvana. However, mentions of bands like Mudhoney, who covered The Dicks’ “Hate the Police” or even early Soundgarden songs or Tad or the Melvins don’t appear. Even if the bands didn’t directly reference Reagan, their connective tissue with the rest of the book would drive home the importance of punk in the 1980s and how it came to influence what would follow in the 1990s. As well, I think about the ways that bands like The Offspring and even Sublime addressed issues of race and police brutality in some of their songs. All of this is mere quibbling, and I know that. None of this is meant to take away from Fitzgerald’s book and its importance. It’s meant to provide more connections to highlight Fitzgerald’s point that punk music, like any music, is of extreme cultural importance because it shapes us and provides a historical lens for the moment.

Finally, I want to leave you with a list of a few current bands that I have discovered over the past few years that continue in the vein of those Fitzgerald discusses and who serve as lines of defense against authoritarianism, fascism, and theocracy. Bands and artists like Soul Glo, Zulu, The Muslims, Cheap Perfume, The Linda Lindas, War on Women, Five Iron Frenzy, Danny Denial, Negro Terror, Soji & Winter Wolf, Gender Chores, and Sharptooth, along with countless others, carry on the tradition of speaking truth to power. Check out a few songs below.