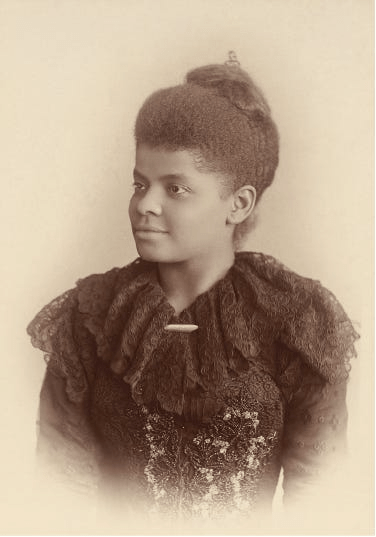

Ida B. Wells begins Southern Horrors: Lynch law in All Its Phases (1892) by quoting a piece she wrote in the May 21, 1892, edition of the Free Speech, a Black newspaper in Memphis. In the piece, she lists recent acts of racial violence across the United States. She writes, “Eight negroes lynched since last issue of the ‘Free Speech’ one at Little Rock, Ark. last Saturday morning where the citizens broke (?) into the penitentiary and got their man; three near Anniston, Ala., one near New Orleans; and three at Clarkesville, Ga., the last three for killing a white, man, and five on the same racket — the new alarm about raping white women.” I had read that passage before, and the city names just flew by because I thought, “One incident among many.” However, I recently picked up Southern Horrors again when someone pointed out that Wells mentions Clarkesville, a town near me. That one mention drove home, as my research into the Bossier Massacre did, the racial violence perpetrated in the space where I reside.

From what I understand, five Black men were arrested for shooting a white man in a nearby town. They were brought to the jail in Clarkesville, and one of the men, denied any involvement but said he saw the shooting. Jim Redmond’s statement led to the release of two of the men. A lynch mob of “one hundred to five hundred” came to the prison demanding that the sheriff give the men over to them. The sheriff refused to do so, and some men in the crowd beat him up. The men took “three charms” — Jim Redmond, Gus Robertson, and Bob Addison — out of the jail and lynched them.

The mob wrapped “long trace chains” and “padlocks” around the men’s necks, and then the mob made the men stand on horses. Someone would slap the horse, the horse would bolt, and the men would drop down, dying by lynching. We do not know the true number in the mob, but we do know that it was a large group. The article ends by stating, “The bodies were left hanging side and side until 3 o’clock this afternoon when the coroner took them down. The verdict was death from unknown hands.” The haunting, infamous final words of reported lynchings, “from unknown hands,” is a lie because even though we only get the names of the victims and the sheriff, the community knew the members of the mob that possibly topped five hundred people.

These people sat in church together on Sunday mornings, walked the streets together to go to the stores, worked in the fields together, drank together, played together. The scene in Clarkesville mirrored scenes all over the United States, as Robert P. Jones points out in his description of Samuel Thomas Wilkes in on the Sunday after Easter in 1899 in Newnan, Georgia. Wilkes was accused of murdering Alfred Cranford, a wealthy white landlord, as he ate dinner and assaulting Cranford’s wife. Wilkes said that him and Cranford argued over a payment that Cranford owed him for work he did. Cranford threatened Wilkes, telling him if he pursued the payement he’d shoot him. The next day, they argued again and Wilkes hit Cranford with an ax.

A reward was issued for Wilkes’ capture, and the governor even chipped in some money. Talk of lynching spread even before Wilkes’ capture, and when he was captured and the lynching set it motion, special trains ran that Sunday from Atlanta for the “festivities.” Two thousand people took the trains. In Newnan, people just out of church, after listening to Sunday sermons, left their houses of worship and walked to a field outside of town, with “a large viewing area” to lynch Wilkes. Men took pieces of Wilkes’ body, and when he arrived in town one day, W.E.B. DuBois saw pieces of Wilkes’ fingers for sale in a shop window. He turned around and went back to Atlanta. This moment turned DuBois into an activist, and he said, “[I realized] one could not be a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negroes were lynched, murdered, and starved.”

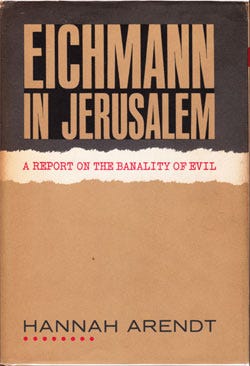

Each of the above stories of individuals lynched at the hands of unknown people reminds me of the Holocaust and Nazi Germany, a topic I have been exploring, especially the connections to the Jim Crow South, a lot over the past few years. Recently, I picked up a copy of Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), the book that arose from her reporting on Adolf Eichmann’s trial for The New Yorker. The trial was an important historical moment because while the Nuremberg trials took place immediately after the war, they focused on the Nazi’s “crimes against humanity,” not specifically on the genocide of millions of Jews. Eichmann’s trial, taking place in Jerusalem, focused specifically on the Holocaust and his role in The Final Solution.

In the first chapter, Arendt writes about the stakes of the trial and the courtroom itself. One of the goals that Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion has, as Arendt notes, was to flush out other Nazis from their hiding spots, specifically those actively involved in the death camps and in the murders. However, as Arendt points out, another side exists to this ferreting out of “criminals.” She writes, “It is one thing to ferret out criminals and murderers from their hiding places, and it is another thing to find them prominent and flourishing in the public realm — to encounter innumerable men in the federal and state administrations and, generally, in public offices whose careers had bloomed under the Hitler regime.”

While Germany’s chancellor Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer claimed only a small number or Germans were Nazis and many helped Jews escape death, only a few asked then, if this was the case, so many remained silent. Ardent notes that a German newspaper concluded they stayed silent “[b]ecause they themselves felt incriminated.” Even if they did not pull the triggers, drive the gas truck, ore cremate bodies they took part, all of them who had a part in the government or in positions of power.

Eichmann’s capture in Argentina paved the way for the arrest of Richard Baer, a commandant at Auschwitz, and of members of the Eichmann Commandos: “Franz Novak, who lived as a painter in Austria; Dr. Otto Hunsche, who had settled as a lawyer in West Germany; Herman Krumey, who had become a druggist; Gustav Richter, former ‘Jewish adviser’ in Rumania; and Willi Zopf, who had filled the same post in Amsterdam.” Even though the public knew of their crimes, evidence being published in Germany years before, they remained free. taking up new professions and living normal lives with no consequences. Eichmann’s trial created a reckoning.

I bring Eichmann up because no reckoning occurred with those who perpetuated the lynchings in Georgia, or elsewhere. The thousands of people who watched the murders of Jim Redmond, Gus Robertson, Bob Addison, and Samuel Thomas Wilkes walked free from the scene of the crime, no one laying a hand on them. They went back to their store counters, bank offices, fields, church pews, and school rooms. They faced no accountability and continued to perpetuate their views without contestation.

Both the Holocaust and Jim Crow were horrendous. They were not the same, by any means, but they are linked. What we can learn from the aftermath of the Holocaust is that accountability needs to occur. It’s part of the healing process. Recognizing the past is a step, yes, but until accountability occurs, in some form, we continue to repeat the past. The individuals who committed the lynchings in 1892 and 1899 are dead, yes, but that does not mean there are not things to do. We can recognize those who were murdered. We can see the ways that the lynchings worked to perpetuate wealth and then how to close that gap. There are things to do, and this is not the post to talk about that. Needless to say, without accountability, thinks remain the same.

What are your thoughts, let me know in the comments or reach out via Twitter where you can follow me @silaslapham.