In The High Desert: black. punk. nowhere., James Spooner details growing up as a Black kid in Apple Valley, California, and being into punk rock. He details the liminality he felt, being seen as not Black enough by his Black classmates or as nonwhite by his white punk friends. When Spooner met Ty, a Black punk kid, at school, he fell in love with it. Punk provided Spooner with an identity, a way to express himself. However, that expression did not correspond to the ways that others viewed him.

Along with the liminality, Spooner also meant being friends with overt white supremacists. Ty and Spooner’s Filth and Fury bandmate, Ethan, lives in a white supremacist home, with his brother George and others espousing white nationalist ideology. In fact, they have Nazi swastikas on the wall and SS tattoos on their hands. Sitting in George’s house, in front of a Nazi flag, Spooner says, “Hanging in proximity to Nazis looks extreme, but it’s not unusual in small-town America. Internalized racism can be a temporary means of survival.” For Spooner, he knows the danger, he knows the hate, but he also knows how finding punk and Ty make him feel about himself.

He continues, “Although my music choices may have given me a pass despite my melanin, I couldn’t help but feeling that things could turn at any moment.” Even with Ethan, who is in the band with Spooner and Ty, things could change on a dime. While this tension covers the entirety of The High Desert, I want to focus on a specific moment where the band plays Black Flag’s “White Minority” and Ethan’s brother George talks about the song being “a white power song.” This moment highlights the ways that art gets misunderstood and changes meanings once it leaves the artist’s hands. It’s a moment that shows, as well, the importance of critical thinking and reading in the understanding of art.

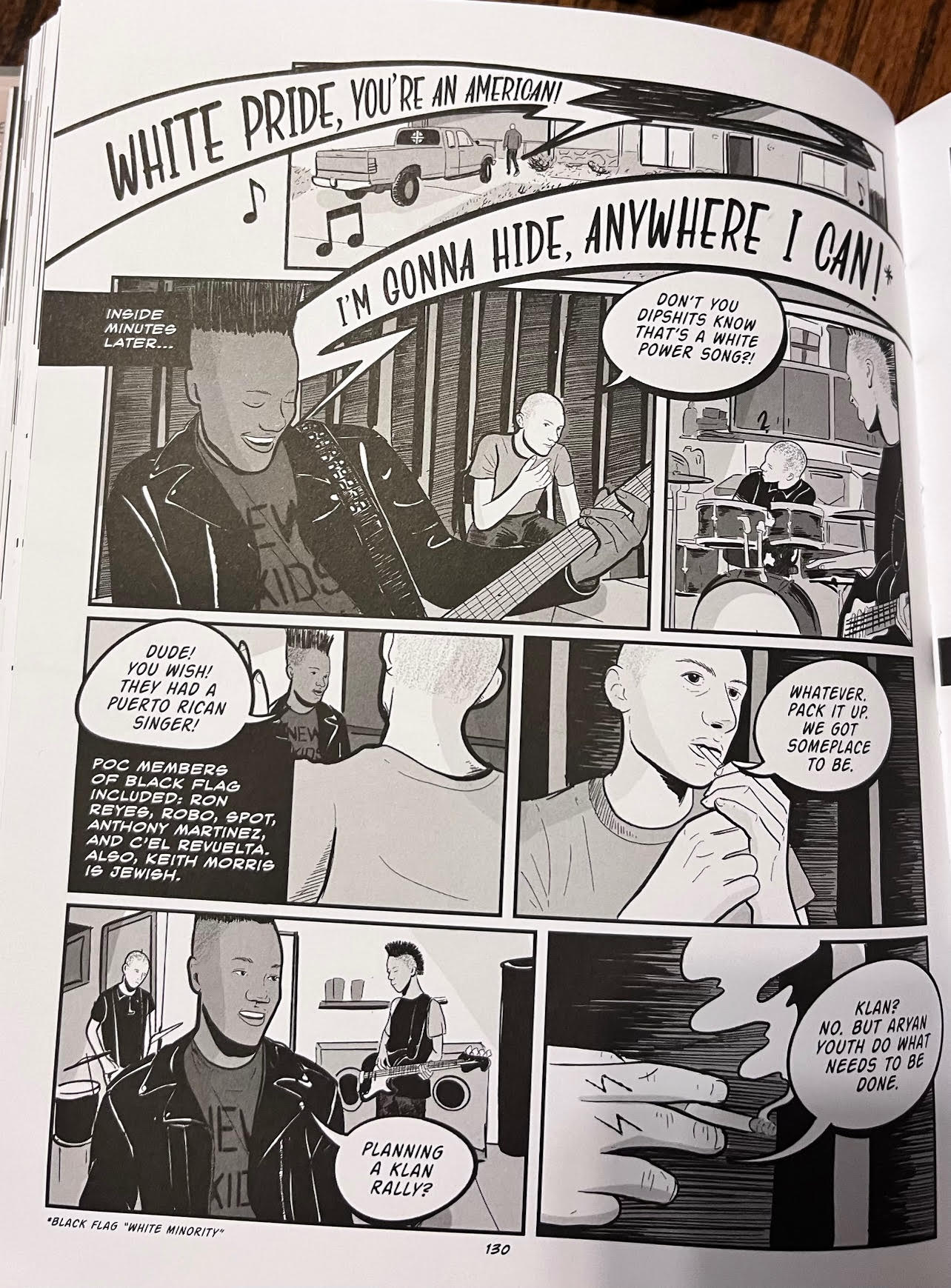

During a Filth and Fury practice at Ethan’s house, the band plays Black Flag’s “White Minority” with Ty singing. We see Ty playing his guitar as he wails the chorus, “White pride, you’re an American. I’m gonna hide, anywhere I can.” George sits in the corner and asks the band, “Didn’t you dipshits know that’s a white power song?” Ethan, seated behind the drums, likes quizzically at his brother. George’s question stems from the song’s lyrics, lyrics that mouth the idea of whites becoming a minority in the United States and the racist language used to describe it. It’s essentially the great replacement conspiracy. On the surface, this is what the song says. It’s from the voice of a white supremacist who espouses these ideas.

However, it is a rejection of those ideas. When asked about the song in an interview for Ripper, Guitarist Gregg Ginn said, “The idea behind it is to take somebody that thinks in terms of “White Minority” as being afraid of that, and make them look as outrageously stupid as possible.” Essentially, it’s a sarcastic song that uses white supremacist ideologies to call attention to the racism of those ideologies. Ty recognizes this when replies to Greg saying, “Dude! You wish! They had a Puerto Rican singer!” Ginn even makes this point too when he adds, “The fact that we had a Puerto Rican (Ron [Reyes]) singing it was what made the sarcasm of it obvious to me. Some people seem to want to take it another way, and somehow think that we’d be so dumb to where a Puerto Rican guy would sing it and it would be — I don’t know how they could consider that racist, but people took it that way.”

For Ginn and bassist Chuck Dukowski “White Minority” uses sarcasm to shine a mirror up to individuals, drawing out, as Dukowski puts it, “existing attitudes.” Dukowski even acknowledges that “[i]f someone is racist, they’ll use it for an athemn,” but he adds that they will do this only for a little while because the song is “so polarized.” Spooner highlights Dukowski’s statement through George’s comments about the song when he claims it as a “white power song.” For me, though, Dukowski’s statement hits at the core of not necessarily a controversy with songs such as “White Minority” but the problematic nature of it.

What do I mean by this? Simply put, I think about the appropriation of the lyrics once those lyrics enter into the audience. While the band and others who know the band know the background, the impetus, and the reason for the song, audiences who have none of this information take on a different meaning. “White Minority” could be heard as a “white power song” even though its a subversive song, using the subversive nature of punk to call out white supremacy. For George, though, this doesn’t matter. The song reinforces his white supremacist beliefs and he uses it as fuel for his racism.

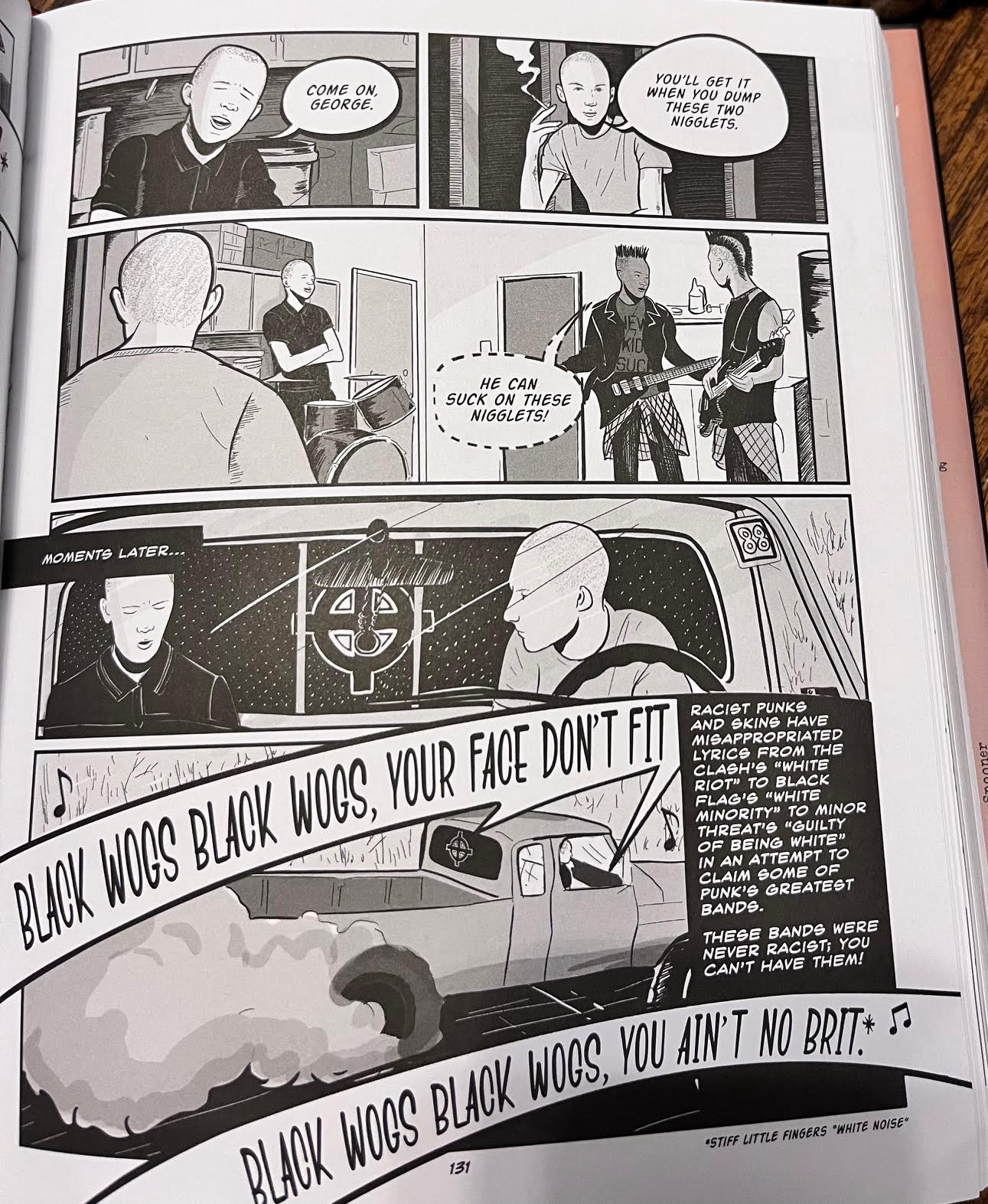

George dismisses Ty’s comment, and he tells Ethan that they need to go somewhere. Driving away, George blasts Stiff Little Fingers’ “White Noise,” and the brothers sing, “Black wogs Black wogs, your face don’t fit. Black wogs, Black wogs, you ain’t no Brit.” The song, written by an Irish punk band from Belfast, is antiracist and antifascist; however, it exist in much the same way that “White Minority” does. The song goes through three verses, describing different ethnicties in England. The first are individuals from the “windrush generation” and later, and Jake Burns uses racist stereotypes, including “n*****” to describe individuals. The second verse focuses on a Pakistani man, again relying on stereotypes, while the third verse brings it back to the band themselves, describing Irish individuals as disposable and inferior, highlighting England’s racism.

Like “White Minority,” George views this song as a “white power song,” one that confirms his beliefs. He doesn’t see the irony and the subversiveness. As Paco on Old Mans Mettle puts it, the song is probably one of the “most offensive anti-racist song ever written.” In its condemnation of racist thought, it reinforces it. When an audience sings the song, do they know its ironic? Do they know it is subversive? Paco notes this when stating, “Anyway, the band had to drop the song from their live set because, Dunning-Kruger effect and all, they’d assumed because they could see the irony, everyone else could. But not everyone did, not even once they’d got to the Irish racist stereotypes, where they described themselves as ‘green wogs.’”

“White Minority,” “White Noise,” and other songs such as The Clash’s “White Riot” or Minor Threat’s “Guilty of Being White” are punk classics. They call out white supremacy, using the language of white supremacy to show its evil ideology. Yet, the irony arises when those same lines get appropriated and used to uphold white supremacy because audience members miss the point. They don’t see the subversion, the sarcasm, the bite. They see their own racist ideas, as Dukowski put it, in the song and just use the song to reinforce their white supremacist thoughts.

Spooner points all of this out, and as George and Ethan drive away singing along to “White Noise,” he says, “Racist punks and skins have misappropriated lyrics from The Clash’s ‘White Riot’ to Black Flag’s ‘White Minority’ to Minor Threat’s ‘Guilty of Being White’ in an attempt to claim some of punk’s greatest bands.” While they have done this, Spooner loudly proclaims, “These bands were never racist; you can’t have them!”

There is a lot more I could say here, but what are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.