In March 2023, Tennessee governor Bill Lee signed the Tennessee Adult Entertainment Act, or the Tennessee drag ban, into law. The ban modifies section 2 of Tennessee Annotated Code § 7–51–1401 which governs the location and business hours of “adult-oriented establishments” and section 2 defines “Adult cabaret.” The drag ban defines an “Adult cabaret performance” as any performance not located in an “adult cabaret” that involves, among other things, “male or female impersonators who provide entertainment that appeals to a prurient interest.” However, a federal judge struck down the law, but similar laws remain in other states.

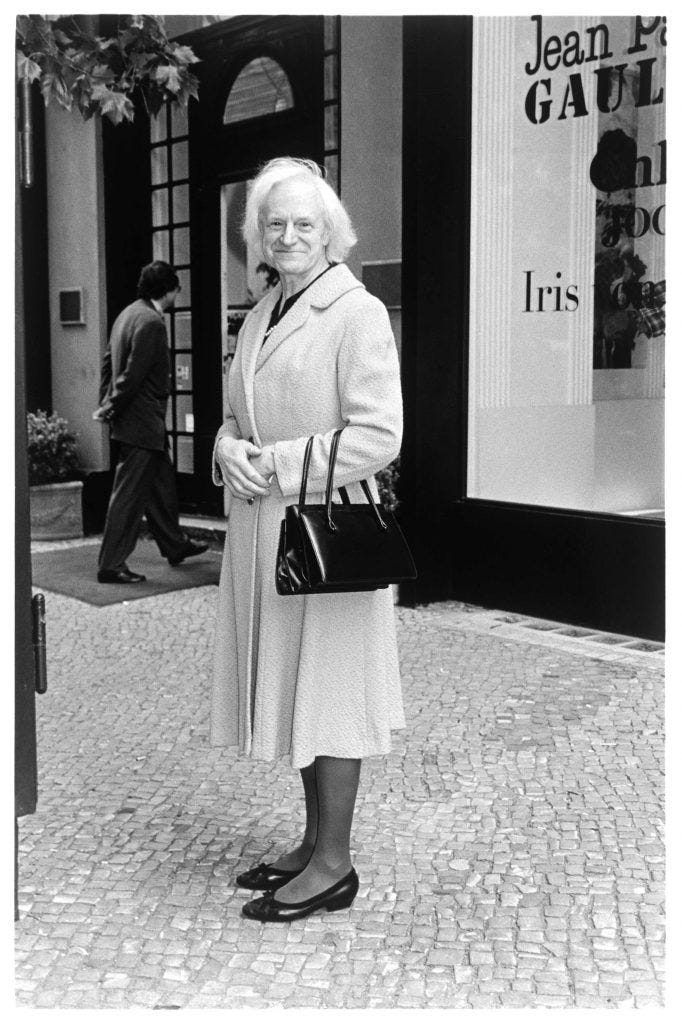

The language of the act is extremely vague, and as Sophie Perry points out, this vague language could have impacted “public Pride celebrations” and many other events, including theatrical performances of plays such as Doug Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize winning play I Am My Own Wife, a play about Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, a trans woman who survived the Nazi and Communist regimes in Germany. I didn’t even know about Wilson’s play until I heard a recent story on NPR’s Weekend Edition about a recent performance of I Am My Own Wife by the Chinkapin Players and directed by Dashboard Schweizer. Hearing Schweizer talk about the play made me want to read it and learn more about Charlotte.

Writing about the lead up to I Am My Own Wife’s Broadway debut, Wright details the struggles he had penning the play. Apart from the writer’s block that stifled the play’s inception for six years, Wright wanted the “play to be a paean to Charlotte,” a text that details LGBTQ history at a moment where, like today, “politicians still routinely decry homosexuality on the evening news and ‘f**’ remains the most stinging of all playground epithets.” Charlotte maintained her dignity and her sense of self amidst crushing regimes that sought to destroy her and others, to murder her and others. She never wavered in her sense of self; however, even amidst all of this, Wright discovered her complicity with the Ministry for State Security (Stasi) in East Germany. She worked, to save herself, as an informant, like many did during the period, and this knowledge left Wright conflicted about how to tell her story.

Wright understood that he had to have Charlotte’s Stasi file in the play because by omitting it he “would render [his] central character benign”; he would turn her into nothing more that a “precious Trannie Granny, rescuing wartime artifacts, running her covert museum, and providing a role model for homosexuals everywhere.” He wanted to tell Charlotte’s story to provide a history that we need to know, to provide us with a person who lived and thrived, who embraced their identity in its completeness. Wright wanted, above all else, to do “justice to the fundamental truths of Charlotte’s singular life.”

While Wright wrote I Am My Own Wife as a one-man show, even though it contains multiple characters, the performance in Tennessee used multiple cast members, even having a younger and older Charlotte. Josefine Parker played the younger Charlotte, and they pointed out the importance of having multiple individuals in the cast because it gives the play an intergenerational feel, bringing people together. As well, as Parker says, the play highlights “this long sense of our history,” pointing out that individuals have been living their lives as their trues selves for a long time and have been resisting oppression because of their identity for a long time as well.

This long arc becomes apparent at multiple points in the play. Doug asks Charlotte “the precise time” she knew she was Charlotte von Mahlsdorf, not Lothar Berfelde. Charlotte tells him that she knew when she visited her aunt Luise, who “since she was fifteen years old . . . never wore ladies’ clothes.” Later, Chralotte’s aunt pulled a book down from the bookshelf and handed them to her. When Charlotte opened Die Transvestiten by Magnus Hirschfeld she “felt a shiver down [her] spine” as her aunt told her to read. Charlotte reads that “it is scientifically impossible to find two human beings whose male and female characteristics match in kind and number,” then she passes the book to Wright and tells him to continue reading. Wright reads, “And so we must treat sexual intermediaries — those individuals who defy the ready classification of ‘man’ or ;woman’ — as a common . . . utterly natural . . . phenomenon.”

Near the end of World War II, as the Allies bombed Berlin, an SS officer pulled her out of an air-raid shelter because “[l]ike the Jews,” as she says, “we were wild game” because of our gender identity and sexuality. Standing in front of the SS commander, Charlotte looked down at the ground because she didn’t want to see them shoot her, and when she looks up and stares at the commander, he ask her, “Are you a boy or a girl?” Charlotte thinks to herself, “If they shoot me, what’s the difference between a boy and a girl, because dead is dead!” Charlotte’s identity doesn’t matter when a bullet pierces her flesh. Out of self protection, Charlotte revers to her childhood, to Lothar, and tells the commander she is a boy, to which he replies, “We are not so far gone that we have to shoot schoolchildren.” The commander would have had no problem shooting Charlotte is she said she was Freiwild, but since she says she is a school age boy, he can’t do it.

Under Soviet control in East Germany, they shut down an LGBTQ bar on Mulackstrasse, and one of the workers comes to Charlotte telling her “our history is decadent” and seeing if anything can be done. Charlotte bought the furniture and transported it to her Gründerzeit Museum to preseve Berlin’s LGBTQ history. When the Berlin Wall went up, “it was finished, gay life” in East Germany. Charlotte says, “The bars, closed. Personal advertisements in the newspaper, canceled. No place to meet but the tramway stations and the pubic toilets. We were not supposed to exist. Persona non grata.” Like the Nazis, the Soviets sought to erase LGBTQ individuals from society, destroying their history and suppressing them. Charlotte would not have any of it and chose “to give the homosexual women and men community in [her] house.”

Charlotte von Mahlsdorf’s story is important, not just because she lived but because she lived, survived, and thrived under oppressive regimes that sought to erase her very existence. As Spree Star, who plays the adult Charlotte in the Tennessee production, to Marianna Bacallao, Charlotte’s story matters because she survived and her story endures. Her story matters because so many others have been lost to history, have died not just physically but in our memory. Her story matters because it reminds us that for every Charlotte von Mahlsdorf there are countless others, who as the dedication to John A. Williams’ Clifford’s Blues reads, lie “without memorial or monument.” Charlotte’s story matters because she highlights that history isn’t dead it isn’t even past, it repeats and morphs. Charlotte’s story matters because she speaks for those LGBTQ individuals who died at the hands of the Nazis and the Soviets. Charlotte’s story matters. Charlotte’s life matters.