Why do we read literature? What goes into our literary choices, those books we choose to pick up off of the shelf and dive into? Do we bring them down from the shelf to escape, for pure entertainment? Do we open them up to learn something new about the world around us? Do we turn the pages to learn something new about ourselves? Or, do we engage with them for other reasons? When I look at a bookshelf and select a book, I do so for a myriad of reasons. I look at aesthetics. I look at what the book can teach me about myself and the world. I look for entertainment. I look for the conversations the books open with other things in my life. Every book does not fit these criteria because some may provide more information than entertainment and vice versa, but this scale doesn’t make any book less valuable than any other work of literature.

Frank Yerby’s The Vixens taught me about Reconstruction in my home state of Louisiana and told me about the 1868 Bossier Massacre, which took place in my hometown and which was one of the bloodiest massacres during Reconstruction. Julie Orringer’s The Flight Portfolio led me to learn about Varian Fry and the Emergency Rescue Commission which helped 2,000–4,000 refugees escape the Nazis in the south of France. Orringer led me to Anna Seghers’ and Victor Serge’s novels on the same period and their own fictionalized retellings of their flight from Nazi pursuit. Leïla Slimani’s trilogy, based on her own family’s history, about Morocco has taught me about Morocco under French colonial rule and post-colonial life in Morocco while Négar Djavadi’s Disoriental taught me about Iranian history and being a refugee in France. All of these books entertained me, taught me something, and expanded my knowledge of the world.

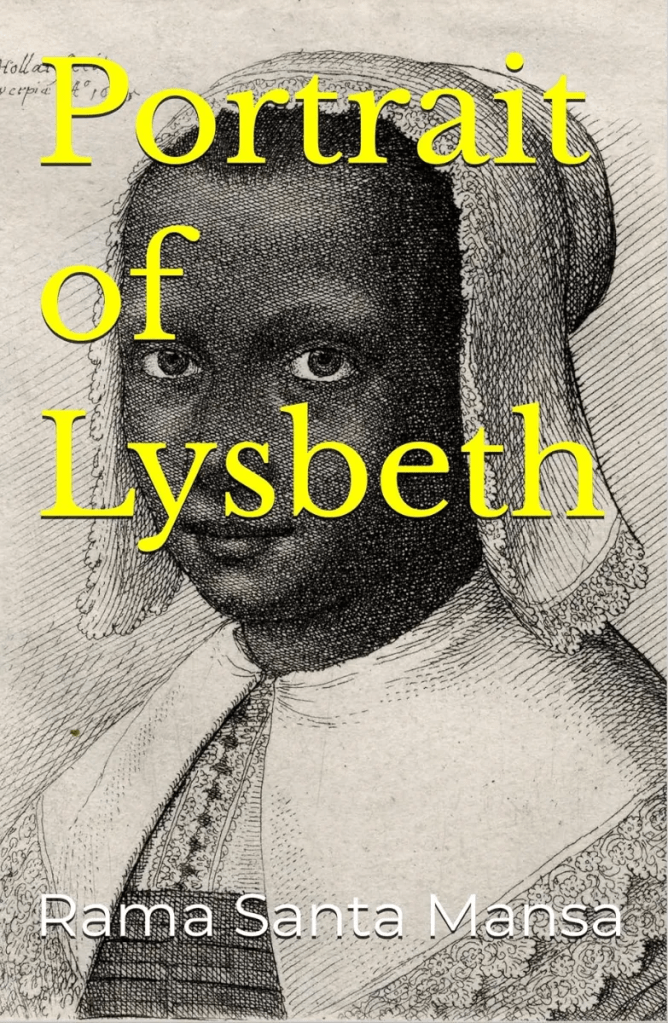

For me, literature should expand my horizons and leave me wanting to learn more. It should lead me to continually ask questions because, as Lillian Smith wrote, “When you stop learning, stop listening, stop looking and asking questions, always new questions, then it is time to die: time to crawl into that small room and pull the cover over you.” Rama Santa Mansa’s debut novella Portrait of Lysbeth does all of this. It informs, leads me to ask more questions, and entertains. It uses literature to fill in gaps in historical knowledge, to pry the reader to face reality and question what they know, urging them to dig deeper, past the fleeting reference on the page, to learn more about Kieft’s War, Peter Stuyvesant, the Swedish House of Vasa, and so much more. Mansa’s Gothic novella works, as she describes it, “as part of [her] academic praxis to address silences in the archives,” those silences that linger in the spaces, the silences that remain muffled, far from the ears of the grater community.

Mansa wrote Portrait of Lysbeth to give voice to the silences, especially as New York celebrates its 400th birthday. The novella, inspired by historical events, tells the story of Lysbeth Luanda, a highly trained and skilled coroner, as she investigates the murders of three women in Sleepy Hollow, partly pulling from Washington Irving’s The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. The novella uses flashbacks to detail Lysbeth’s life from being born free to her enslavement and indentured servitude to her training as a coroner and the solving of the Sleepy Hollow murders. Through this path, Rama addresses, as she puts it, “New York’s early history of genocide, slavery, settler colonialism, racism, homophobia, misogynoir, and child abuse.”

Rama dedicates Portrait of Lysbeth to the protagonist’s real-life inspiration, Lysbeth Anthonijesen, a free-born Black woman who began working in the homes of white colonists at a young age. She confessed to stealing from her employers and confessed to arson in 1663. The court sentenced Lysbeth to death by strangling but commuted that sentence at the last minute. However, they walked her out of the courthouse letting her believe she would be executed. Instead, the court sentenced her to enslavement in the Creiger family, the owners of the house she burned. The Creigers became her enslavers and we do not know, past this point, what Lysbeth thought. Rama creates “an alternative destiny for Lysbeth,” giving her voice and agency.

Portrait of Lysbeth provides readers with a Gothic narrative that, like all Gothic narratives, uses our fears to make us confront the real issues of society. Rama’s novella works within the African American Gothic tradition, or what John Jennings and Stanford Carpenter call the Ethnogothic, pushing back against the conservative impulses of early Gothic writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and others. In this manner, Rama’s novella exists within a long line of Ethnogothic texts, using the fear inducing Gothic to push back against racism, misogynoir, classism, sexism, and oppressive isms that impact individuals, including antisemitism through the depiction of Lysbeth’s mentor Doctor Avraham Henriques.

The lust for power lies at the heart of villainy in the novel, and for me, the counter to that lust lies in Avraham’s response to Lysbeth when she asks him what he thinks he would have done if he “had been born an heir to a great plantation fortune.” This is a question I ask myself all of the time, in a different manner. I ask, “What would I do if I was wealthy? How would I inhabit the world?” Avraham initially tells Lysbeth that he wants to tell he would not be an enslaver and lust for power, and this response ponders Lysbeth. He continues by explaining,

The lust for wealth has destroyed many people. Some souls do not need the promise of lucre to become inhuman. They had the evil inclination from the start. I never desired extreme wealth. A respectable living was my heart’s only desire. I have had a good life in medicine. The life of the mind has given me a worthy purpose. Maybe it will give you a purpose, too.

While Avraham is not the focus of the novella, his role and comments encapsulate how we approach literature and knowledge, something that Portrait of Lysbeth does as well through the resurrection of Lysbeth from the archives. “The life of the mind” opens up our world to those around us, informing us, and hopefully leading us to seek a better world for everyone. It helps us see ourselves and others in new ways.

When I read a book like Portrait of Lysbeth, I think about the ways we remember the past and those who came before. I think about Lillian Smith’s words to Studs Terkel in 1961 when she spoke about people reading her books. She told him that when people stop reading her books she views it as death. She said, “Now that is an acceptance I call death, you see. Death to the writer. Death comes to the writer when people stop reading her books.” In the same manner, when Lysbeth Anthonijesen’s voice disappears following her final trial, she disappears. Rama brings Anthonijesen back to us through a fictional, alternative path for her life. She also brings back to us Samuel Mosely, the villain in the narrative, and many others. In this manner, Rama provides us with a novella that entertains, instructs, and causes us to reflect. That is the power of literature, and that is the importance of texts such as Portrait of Lysbeth, ones that carry on centuries long conversations with the past, the present, and the future.

You can read an excerpt of Portrait of Lysbeth over at brittle paper. What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on Twitter at @silaslapham.