For a number of reasons, I have never been a huge Superman fan. When I was younger, and into speculation, I bought Superman #75, “The Death of Superman,” in hopes that it would increase in value. Today, I no longer have that issue, and I have no clue what I did with it. Even though I’ve never really been a Superman fan, I had to include him in my “Who Watches Superheroes?” course because Superman is the progenitor of what we define today as superheroes, characters that correspond to Peter Coogan’s definition of the superhero because they exist on a matrix that encompasses mission, powers, and identity (MPI). Superman embodies MPI to a tee, but it wasn’t always like that.

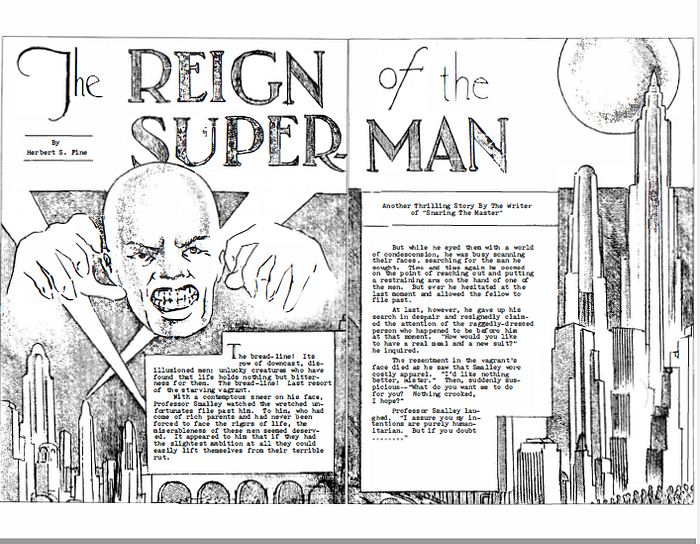

When most people think of Superman’s debut or origin they envision of the cover of Action Comics #1 (1938) where Superman holds a car above his head before smashing it on a rockface. Five years earlier, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, while still in high school, began publishing their Science Fiction, a pulp fanzine in the vein of other publications at the time. “The Reign of the Superman” appeared in the first issue with Siegel writing the text and Schuster providing the illustrations. This story, as Aldo Regaldo points out, “was the first incarnation of the character that eventually became America’s first modern superhero.” The story isn’t a heroic story or one that really creates the superhero, but it serves as lens to look at the ways that Superman and superheroes arose during the mid-twentieth century.

“The Reign of the Superman” is, at its core, a story that speaks to the historical moment of the Great Depression, economic insecurity, fears of modernity, and fears of global conflict, among other things. The first paragraph foregrounds these issues when the narrator states, “The bread-line! Its row of downcast, disillusioned men; unlucky creatures who have found that life holds nothing but bitterness for them. The bread-line! The last resort of the starving vagrant.” Professor Smalley, a chemist who has acquired fragments of a meteor, stalks the bread-line looking for a subject to test a concoction he made from the meteor to see the effects before using the substance on himself. It is here that he comes across William Dunn and uses Dunn as a lab rat for his experiment. Smalley views the individuals in the bread-line negatively, saying that their poverty stems from their lack of motivation to work because even “if they had the slightest ambition at all they could easily lift themselves from their terrible rut.” He plays into the myth of the American Dream, and through his role as a chemist, also, as Regaldo writes, “represents modern scientific rationalism.”

Smalley woos Dunn with the promise of food and money, and when he brings Dunn the food he places the concoction in the coffee, at which point Dunn escapes Smalley’s residence, fleeing to the park. There, he begins to feel weird and notices that he can hear everyone’s conversations, read people’s thoughts, and see extremely long distances, even observing a scene between two entities on Mars. All of this leads Dunn to think about ways he could use his “powers” to trick people into giving him money. After tricking a few people, Dunn realizes he can see a few hours into the future and observes a man reading the next-day’s paper on a park bench. He uses the headlines to place bets on races and other events and rakes in the money. All of this leads Dunn to pursue bigger plans, namely world domination, even attacking a global peace conference.

Smalley realizes the powers that the meteor fragments gave Dunn, and he attempts to take the concoction. Smalley tells Dunn that the two of them can rule the world together. However, since Dunn can read individuals’ thoughts, he knows Smalley’s plan to take the concoction and then kill Dunn, so Dunn kills Smalley and seeks to control the world by himself. Dunn’s plan doesn’t come to fruition, though, because at the end of the story Dunn realizes his powers are fading and that within a day or two he will no longer have them. When that happens, he finds himself musing that he will be back on the “bread-line” with others hoping to get food. Upon recognizing he will lose his powers, Dunn tells a reporter whom he tried to attack, “If I had worked for the good of humanity, my name would have gone down in history with a blessing — instead of a curse.”

Dunn doesn’t use his powers to help the oppressed, as Superman does when he makes his comics’ debut in 1938. Rather, he uses his powers to try to gain power and prestige. This, of course, differs from the “pro-social and selfless morals” that Coogan says represent the superhero’s mission. Dunn and Smalley use their powers to better themselves, becoming selfish and violent in their attempts to acquire power over others. Dunn does this to navigate the urban modernity that oppresses him and causes him to stand in the bread line seeking assistance to merely survive. He sees others, like Smalley, who have money and thinks that money will solve his problems. While it solves his temporal needs, it harms his emotional being because he becomes selfish, egotistical, and narcassistic. When he realizes he will lose his powers, it all comes crashing down and he thinks about how he could have helped society instead of oppressing individuals.

Regalado points out that Dunn’s realization at the end of the story highlights how Shuster and Siegel reject the values of competitive aggression of an an earlier age, stressing, albeit vaguely, the virtue of serving the community instead.” While they did this, pointing out the problems with and “more insensitive realities of laissez-faire capitalism,” they also played into their “middle-class sensibilities.” These tensions are what appear in a lot of the texts I’m teaching this semester in “Who Watches Superheroes?” The tensions of power, no matter who has it, play out in many of the texts my class will read this semester, and “The Reign of the Superman” foregrounds this tension through Dunn’s acquisition and misue of his power to his return to the bread line at the end of the story.

“The Reign of the Superman” is an interesting story, and it provides us with a grounding for the superhero genre that would emerge later in the 1930s. While not a distinctly superhero story, and more in line with supervillains, Shuster and Siegel provide us with a narrative which deals with many of the themes and issues that arise within the genre, namely the role of the superhero and the tensions that the superhero exists within.

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on Twitter at @silaslapham.

Pingback: Superman wasn’t always so squeaky clean – in early comics he was a radical vigilante – We See & Show

Pingback: Superman war nicht immer so sehr sauber - in frühen Comics war er eine radikale Wachsamkeit - Germanic Nachrichten

Pingback: Superman wasn’t always so squeaky clean – in early comics he was a radical vigilante – TomFlash News

Pingback: Superman wasn’t always so squeaky clean — in early comics he was a radical vigilante - Energy And Markets Now

Pingback: Superman wasn’t always so squeaky clean — in early comics he was a radical vigilante - Nxt Level Profits

Pingback: Superman wasn’t always so squeaky clean – in early comics he was a radical vigilante | New Pittsburgh Courier