During Dr. Manhattan’s public reveal in March 1960 in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen, a newscaster stares into the camera and says, “The Superman exists, and he’s American.” Watchmen takes place in an alternate history where the United States won the Vietnam War, Richard Nixon remains president in 1985, and superhero “vigilantes,” inspired by the appearance of Superman and others in the late 1930s, protect individuals from criminal masterminds and other crime. Dr. Manhattan (Jon Ostermann) is really the only true superhero in the narrative, the only Watchmen with super powers. He can manipulate matter, transport himself and others anywhere in the universe, see the future and the past while living in the present, and more. In essence, he is a “superhero,” at least in regard to powers.

The newscaster’s pronouncement of Dr. Manhattan being “Superman” and “American” is important because it plays into Cold War Rhetoric and the idea that the United States has an upper hand in the nuclear standoff with the Soviet Union because they wouldn’t dare attack the United States when the United States has Dr. Manhattan. The newscaster’s quote comes from Professor Milton Glass, the author of Dr. Manhattan: Super-Powers and the Superpowers. In the fictional excerpt of Glass’ book, he writes that he did not refer to Dr. Manhattan as “Superman.” Correcting the quotation, he writes that he said, “God exists and he’s American.” While superheroes arose from mythology and modern ways to think about deities and religion, Glass’ use of “God” is important, especially considering the overall themes within Watchmen and Dr. Manhattan’s ability to interact in catastrophic events and annihilate entire populations with the snap of his fingers.

One of the overarching themes within Watchmen centers around the ability of humans to commit genocide and mass destruction. This comes up in many of the books I am teaching this semester, including books such as Victor Serge’s Last Times and Anna Seghers’ Transit, both of which I am teaching in my “The Reverberations of World War II” course. In Watchmen, though, this theme takes on another layer with discussions of Dr. Manhattan as a “God,” as an all-power, omnipotent being who has the power to wipe out humanity. Edward Blake (The Comedian) expresses the fears that Dr. Manhattan represents as he sits at the foot of Moloch’s bed drinking and ranting about his past.

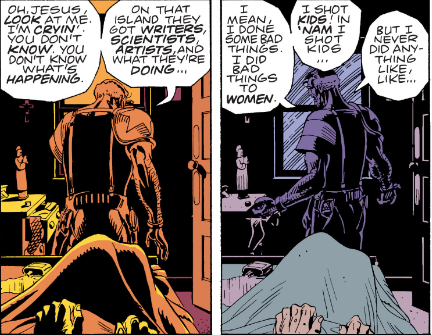

He tells Moloch that he started out “cleanin’ up the water fronts,” essentially dealing with individual criminals, one person or small group at a time. Yet, he realizes that the world and evil don’t work individually; they work systematically, and as he continues fighting crime, he sees the systemic layers of corruption, eventually working for the government. Blake discovers the plan concocted by Adrian Veidt (Ozymandias) to bring the world together and the ways he sought to achieve it. Blake tells Moloch, “Oh Jesus, look at me. I’m cryin’. You don’t know what’s happening. On that island, they got writers, scientists, artists, and what they’re doing . . .” He tells Moloch he has killed individual people and done “bad things to women,” but he has never committed mass-scale genocide, and Veidt’s plan, while seeking to unite, will do just that.

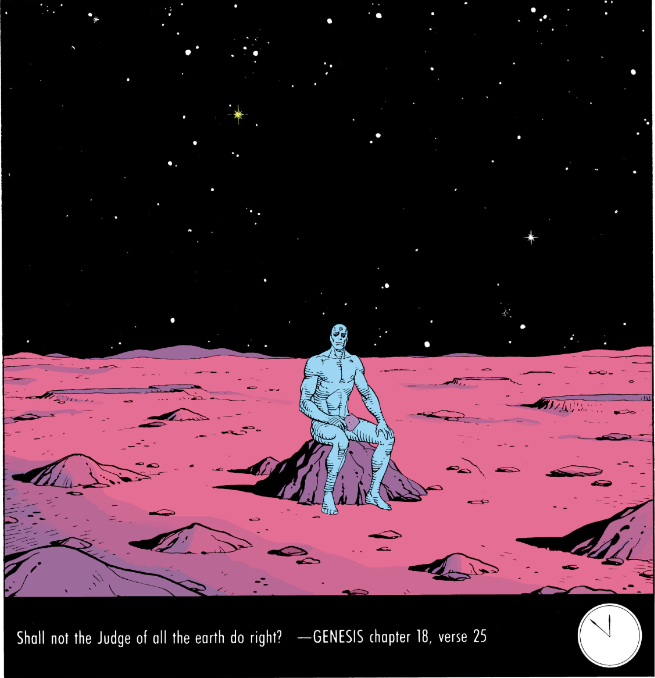

When the Soviets invade Afghanistan, the world braces for nuclear war, and after a contentious interview, Dr. Manhattan flees the planet, transporting himself to Mars. On Mars, he roams the surface, thinking about humanity and existence as politicians discuss the threat of nuclear warheads launching. At the end of Chapter III, panels move back and forth between Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, and other high-level military and government officials assessing the threat of war and Dr. Manhattan walking across the barren-landscape on Mars. Nixon’s laments that he always hoped someone else would have to make the decision on whether or not to fire nukes at the Soviets, and the issues concludes with him thinking back to naval battles and the impact that the unpredictable wind had on the outcome of the battles at sea.

Looking at the screen, he says, “The wind’s a force of natire. It’s totally impartial. . .” At this moment, the panels shift, and Nixon’s final words in that sentence appear above an image of Dr. Manhattan on Mars. Nixon concludes, in reference to the wind, that it is “totally indifferent.” This indifference epitomizes Dr. Manhattan. He could end all of this. He could have stopped Blake from murdering a woman he got pregnant in Vietnam. He could have stopped Lee Harvey Oswald from assassinating John F. Kennedy. He knew these things would happen, you he remained “indifferent.”

Glass’ statement that “God exists and he’s American” comes to mind in this moment. Thinking about Dr. Manhattan’s backstory, his father’s occupation as a watchmaker, and the repeated references to watches and time throughout the series, Dr. Manhattan becomes a God who, while knowing what will happen, removes himself from the events, even though he tells people what will happen, and remains “totally indifferent.” This indifference recalls, in many ways, Deism, a philosophical idea that arose during the Enlightenment and to which many founding fathers in the United States adhered to. In a nutshell, Deists believed in a divine being who created life on Earth and set it in motion, as one would wind a watch or a clock. Once wound, thought, the deity removed themselves from the equation, allowing humanity and existence to proceed forward. The deity does not interfere in the universe after its creation.

On Mars, Dr. Manhattan contemplates creation. He picks up sand from the surface and lets it run through his fingers as he thinks, “Gone to a place without clocks, without seasons, without hourglasses to trap the pink shifting sand.” He levitates into the air and says he is ready to begin creating structures on Mars. As he creates, he think about the bombs that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, linking them to the watchmaking and the watch pieces that his father threw out of the window once he heard about the bombing of Hiroshima. He asks, “Who makes the world?” Responding to his inquiry, he thinks, “Perhaps the world is not made. Perhaps nothing is made. Perhaps it simply is, has been, will always be there, a clock without a craftsman.”

Dr. Manhattan creates a structure with cogs and gears, a structure that looks, in many ways, like the watch parts his father throws out the window. He bcomes the “craftsman,” creating things out of nothingness, setting them into motion. He becomes the omipotent, knowing how existence will play out. He becomes the “totally indifferent” deity who exists, creates, and knows but who remains aloof from everything, refusing to intervene with it.

The final panel at the end of Chapter III shows Dr. Manhattan siting on a rock on the surface of Mars before erecting the structure, holding a photograph of him and Janey Slater taken on a boardwalk in his hand. He sits there, in his role as a “God,” amidst the stars of the universe, in isolation and loneliness. The final words in the issue, below the last panel, come from Genesis 18:25 when Abraham tasks God, “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?” I want to pick up here in the next post.

Until then, what are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on Twitter at @silaslapham.