A few overarching themes appear in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen, each involving our connections with the divine and with others who inhabit the world with us. Recently, I wrote some about this, specifically with Dr. Manhattan’s thoughts about the divine and humanity. Today, I want to continue examining these themes, notably through the use of Genesis 18: 25 at the end of Chapter III and through Rorschach’s comments about himself and his feelings of being alone during his interviews with psychiatrist Malcolm Long.

At the end of Chapter III, Dr. Manhattan has retreated to Mars, fleeing any decisions that he could make regarding the looming war that hovers over the novel. Even though Milton Glass refers to Dr. Manhattan as “God,” Dr. Manhattan does not interfere in the deeds and acts of humankind. Even though he originated as Jon Osterman, he does not use his powers to interfere in the everyday machinations of humanity, refusing to stop Lee Harvey Oswald from assassinating John F. Kennedy or Edward Blake from murdering a Vietnamese woman he got pregnant. Dr. Manhattan knows the past, present, and future, yet he removes himself from altering any of it, even when he knows doing so will save lives.

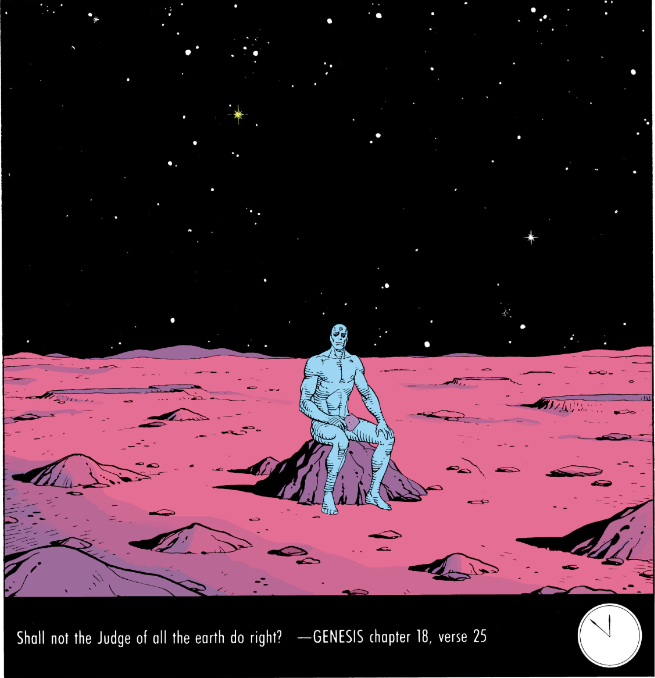

Dr. Manhattan’s position, as a “deity” that can alter existence but chooses not to interfere corresponds, in many ways, with the use of Genesis 18: 25 at the end of Chapter III and leading into his conversation with Laurie about coming to humanity’s aid in Chapter IX. Beneath the final panel of Chapter III, Moore and Gibbons pose a question that Abraham asks God in Genesis 18. Abraham asks, “Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?” Abraham asks God this question after God tells him that he plans to destroy Sodom.

To understand the way that this verse works in Watchmen, we need to look at the Biblical context, specifically Genesis 18:16–33. In these verses, God has just left Abraham and Sarah after telling them that, even in their old age, they will conceive a child, thus fulfilling God’s promise to Abraham earlier that he will be the father of Israel. As God leaves towards Sodom, God ruminates on whether or not to tell Abraham about the plans for destroying the city. God decides, since “Abraham shall become a great and mighty nation, and all the nations of the earth shall bless themselves by him,” that God should tell him the plans (Genesis 18:18). God tells Abraham that he plans to go to Sodom and Gomor’rah to see if they have repented from their sin; if they have not done so, then God will destroy them.

When Abraham hears this, he asks God, “Wilt thou indeed destroy the righteous with the wicked? Suppose there are fifty righteous within the city; wilt thou then destroy the place and not spare it for the fifty righteous who are in it?” (Genesis 18:23–24). These questions start a bargaining sessions between God and Abraham, which begins with God saying if 50 righteous people inhabit the cities he will spare them and ends with Abraham bargaining God down to ten righteous people. The question that Abraham asks in Genesis 18:25 appears in the start of this session, and the entire verse reads as follows, “Far be it from thee to do such a thing, to slay the righteous with the wicked, so that the righteous fare as the wicked! Far be that from thee! Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?”

Here, Abraham implores God to do “right.” Let that sink in for a second. Abraham, a human, implores God, a divine being who created the heavens and the earth, to do “right” by sparing the “righteous” who live amongst the “wicked.” The use of this Biblical moment in Watchmen drives home one of the overarching questions in the book, “What do we do when those who can change the outcome choose to remain inactive and let the destruction happen?” From a theological perspective, Dr. Manhattan embodies the divine, a deity with powers like, as Glass say, “God.” He embodies the Deists belief in a divine being who sets the world in motion then lets it play out, allowing existence to choose its own path without interference.

As well, he embodies the divine entity that we can question and debate with, the entity that we can challenge and implore to do “right.” This is what Laurie and Dr. Manhattan’s conversation on Mars revolves around, the same conversation and bargain between Abraham and God. Dr. Manhattan refuses to save Earth and plans to build a new existence on Mars, and Laurie calls him callous and tries to get him to see that Earth is worth saving. Eventually, Dr. Manhattan comes around after Laurie learns about her father and her past.

At the end of Chapter IX, Dr. Manhattan agrees that life is not meaningless because he has seen what love can produce, even amongst hate and chaos. Laurie discovers that her father is Edward Blake, the man who raped her mother. She discovers that her mother and Blake had a consensual encounter years later that produced her. In explaining why he changed his mind, Dr. Manhattan lays out statistically the chances of a sperm and egg fusing to make an individual. he says,

And yet, in each human coupling, a thousand million sperm vie for a single egg. Multiply those odds by countless generations, against the odds of your ancestors being alive; meeting; siring this precise son; that exact daughter; until your mother loves a man she has every reason to hate, and of that union, of the thousand million children competing for fertilization, it was you, only you, that emerged.

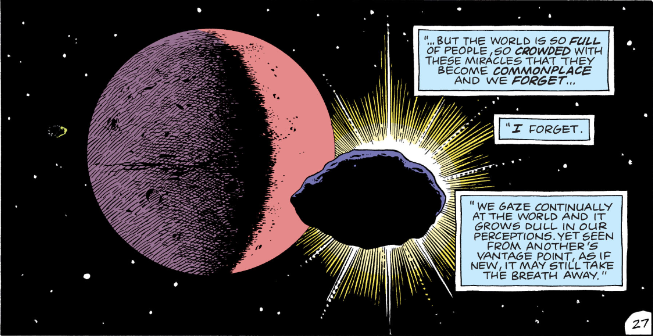

Laurie responds by saying that if he can say that about her existence Dr. Manhattan can say the same about “the whole world.” He agrees, telling her that the mass of humanity on Earth is so crowded that these “miracles . . . become commonplace and we forget.” We look at the world from our own perspectives, and when we start to view it from the perspectives of others, our perceptions change. Laurie helps to change Dr. Manhattan’s perspective on humanity just as Abraham changes God’s perspective on Sodom. This moment leads Dr. Manhattan back to Earth to do what he can to save it.

Many of us grow up learning that we can’t challenge or question or push back on the divine. We don’t think about Abraham doing just that or Jacob wrestling with God. We don’t think about Abraham imploring God, the omnipotent, omnipresent, and righteous, to do what is “right” by saving Sodom because destroying it would kill the righteous along with the wicked. We don’t grow up learning that God can change their mind, and that we can argue with God. This relationship, this intimacy, where one feels free to question and challenge, lies at the heart of the story in Genesis and the heart of Watchmen. It stretches beyond the theological and religious to the everyday. We must not be afraid to question and challenge one another and to have others question and challenge us. That is how we grow, and that is how we create an encompassing society that works together for the betterment of all.

There is so much more to say about Watchmen, and hopefully I will have a few more posts in the future. Until then, what are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on Twitter at @silaslapham.