Whenever I go to a used bookstore, I typically find a book I have never heard of and pick it up. On one such trip, I saw a copy of Rolf Hochhuth’s The Deputy, A Christian Tragedy (1963) for 0.75¢. The description on the back of the book intrigued me because it points out that the play caused a controversy when it premiered because of its “treatment of Pope Pius XII . . . and the Church during the Nazi persecution of the Jews.” This summary stood out to me, especially since I have been researching the intersections between the Jim Crow South, Nazi Germany, and Christianity. I have not, as of yet, done much on the role of Christians during the Holocaust, so I knew I had to pick up this book, not merely for the play itself but also for Hochhuth’s appendix where he details the research he conducted for The Deputy.

Throughout The Deputy, countless Church leaders, resistance figures, and Nazis argue that Hitler did not go after the Church because, even if he disagreed with them, he felt that they had the power to move the masses against him. As well, the Church, in Rome, did not move against vociferously against Hitler because they saw him as a beachhead against Soviet expansion of Communism into the West. As Hochhuth notes, “In 1940 Hitler, after a talk with Mussolini, expressly forbade [Alfred] Rosenberg to commit any provocations against the Vatican, and in August 1941 he ordered the euthanasia program halted because of protests from the churches.” Hochhuth points out that we can understand Hitler’s views if we look back further to a November 1937 piece in Der Angriff that would be reprinted as a Nazi pamphlet in 1938.

In that article, the author asks why the Nazis should even worry about the Vatican, a “ridiculous little corner of the earth in the capital of the one-time Roman Empire.” Ultimately, the writers argues, that the Vatican poses a threat and problem because world leaders such as Roosevelt, Dimitroff, Chamberlin, and others, while “very influential persons,” will die and “[t]omorrow no one will give a damn about them.” However, the Pope remains, not in the embodiment of the same person but in the embodiment of ideas. The author states, “They remain the same for decades; when they are replaced, they are replaced by others of the same school; and they follow the same policies, century after century” and they rule over, at that time, “four hundred million ‘faithful’ throughout the world.” The author points out that the Nazis know about ideas and how ideas and faith, not money, weapons, and economics alone, bring about monumental change. Thus, poking the Vatican and having it deploy the world’s “faithful” against them, would crush the Nazis.

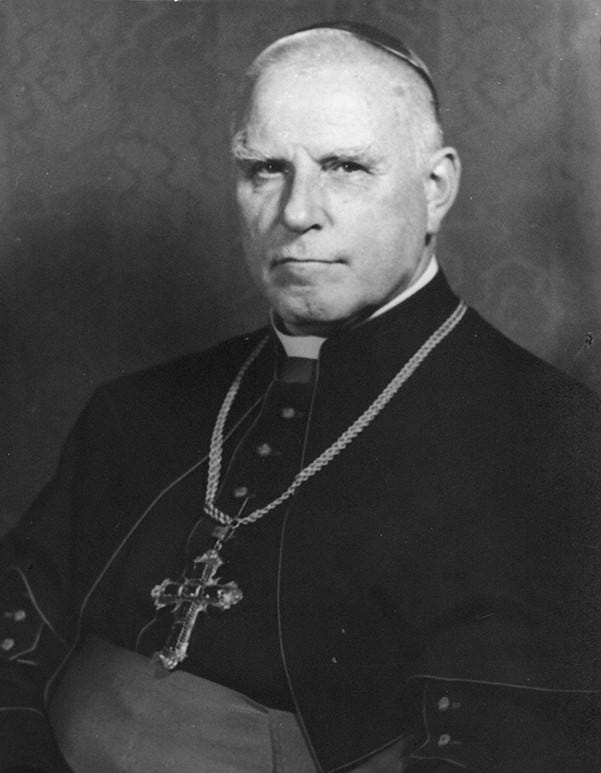

Likewise, the Nazis thoroughly understood the power of the Church in mobilizing the masses to their world view. While they viewed it as a threat, they also viewed it as a powerful weapon. Speaking with Heinrich Himmler in 1942, Hitler said, “If filled churches help me to keep the German people quiet, then in view of the burden of the war there can be no objection to them.” Even when Clemens August Graf von Galen, the Bishop of Münster, spoke out against Nazi practices, leading to the halting of the euthanasia program in August 1941, Hitler did not go after him. While Hitler didn’t confront Galen publicly because of the sway of the Church, he did state that when the Nazis achieved victory that Galen would be “sent before the firing squad.” Hochhuth continues by stating, “[Hitler] also remarked ironically that if the Bishop did not succeed in being called to the Collegium Germanicum in Rome before the end of the war, there be an accounting with him down to the last farthing — after the war.”

Galen comes up a few times in The Deputy, both by those who admire him and by the Nazi command who despise him. When Father Riccardo Fontana speaks with the Nuncio of Berlin in the first scene and points out Nazi atrocities, the Nuncio states, “It’s strange they haven’t dare touch the Bishop Galen, even though he publicly denounced, right from his pulpit, the murder of the mentally ill. Hitler actually gave in on that.” Even while Hitler gave in, he, along with Himmler, Goebbels, and others, understood that in order for fascism to succeed, they needed the Church. The Nuncio tells Riccardo that Hitler has to reckon with the power of the Church. He says. “Consider how in the United States day by day the Catholics’ power grows — Herr Hitler has to reckon with that, too. He will discover what his friends, Franco and Mussolini, learned long ago: Fascism is invincible only with us, when it stands with the Church and not against it.” Hitler understood the power of the Church and the reasons why he could not reproach Galen.

During a gathering of Nazi officials and others, Professor Hirt and Adolf Eichmann address why Hitler did not publicly reproach Galen. Hirt proclaims, “On the other hand think of Galen that blabbermouth. I was fit to be tied, let me tell you, when the Führer called off the euthanasia program . . . just because of the rabble-rouser of a bishop.” Adolf Eichmann responds by mocking Galen and discussing how “the fox put on his vestments, clutched his crook and popped the miter on his head” when they came to take him away for an interrogation. When Galen told the Gestapo he would walk instead of getting in the car, they gave up because, as Eichmann says, “They were afraid of the populace in Münster. Rightly so — think of the fuss the people would have made. To my mind, the Führer shows his stature the way he spares religious feelings in wartime.” Eichmann points out that instead of fighting Galen and the Church, Hitler and the Nazis, while complaining in private, understood the danger in doing anything to Galen.

Later, when Riccardo speaks with his father, imploring him to convince the Pope to speak out against the Holocaust and to abrogate the Concordat, he tells his father about a conversation he had with Herr von Hassell in Potsdam. While Galen fought to end the euthanasia of individuals with mental disabilities, he did not speak up for the Jews. Von Hassell asked Riccardo, “Why did Rome let Galen fight alone?” to which Riccardo responded with a question of his own, “Why did Galen not also come for to defend the Jews? Because they mentally ill were baptized?” Riccardo’s father asks him to not judge Galen “not risking his life for the Jews as much as Christians” and asks him, “Do you know, Riccardo, what it’s like to rick your life?” Riccardo pushes back and says he admires Galen but the Church cannot stand by as the Nazis continue to commit atrocities, atrocities which the Vatican and the world have a clue about due to reports coming out of Poland and elsewhere.

Even though the Nazis didn’t agree with Galen, they used him to further their means since he did not speak out against their atrocities against Jews. Stephan Warner states that Goebbels, when he came to Münster didn’t make himself know because if he did he would have had to arrest Galen. If that happened, Warner points out, “Galen would have become a martyr whose fate might have inspired millions to uncompromising commitment against the totalitarian regime. The Propaganda Minister knew only too well what this particular opponent could accomplish.” If Goebbels did anything, Münster, Germany, and the world, would quickly turn on the Nazis because, as Hitler noted, while world leaders may pass away, the Church remains.

In the next post, I will focus on two moments in The Deputy where discussions of inaction occur. Until then, what are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.