Ian Kershaw’s The “Hitler Myth”: Image and Reality in the Third Reich, traces the image of Hitler in Germany from the failed putsch in 1923 all the way to the regime’s demise in 1945. Kershaw points out that the historical priming for a myth in an all-powerful Führer who would save the nation, dating back to the nineteenth century. While many groups ebbed and flowed in their dedication to Hitler, Kershaw consistently points out that those who grew up either during the rise of the Nazi party or during their reign did not oscillate between approval and disapproval, mainly siding with the Führer at every turn.

This devotion to Hitler and the myth surrounding him should come as no surpirse in a populace raised on the “Hitler myth.” Even when defeat seemed imminent following the failed invasion of Russia, Kershaw writes, “A large portion of the younger generation, growing up during the Nazi era and highly impressionable, had been fully exposed to the suggestive force of propaganda and had succumbed more uncritically than any other section of the population to the emotional appeal of the ‘Führer myth’.” Children encountered indoctrination in school, preparing them to become members of the Deutsches Jungvolk in der Hitlerjugend (10–13 years old) then the Hitlerjugend (14–18 years old) when they came of age.

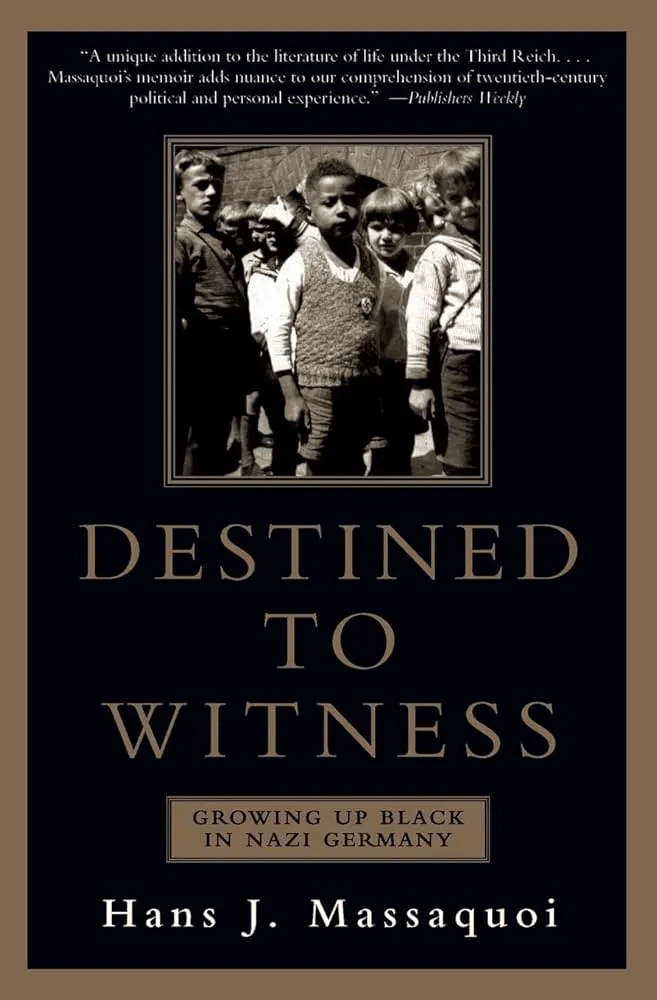

The lure of the “Hitler myth” extended deep for young people. Growing up in Hamburg, Germany, Hans Massaquoi, the son of Liberian father and a German mother. Born in 1926, Massaquoi experienced, firsthand, the indoctrination that Kershaw references. During school, Massaquoi experienced racists comments from administrators and fellow sudents, especially after the Nazi came to power nationally in 1933. Massaquoi saw the Nazis parade through the streets. He saw their uniforms, and they impressed him.

At ten years old, he and his classmates watched the 1933 film Hitlerjunge Quecks at school, a propaganda film railing against communism. In the film Quecks “grows up,” as Massaquoi writes, “in a predominantly Communist Berlin slum. His father, an alcoholic Communist sympathizer,” abuses his family. The blonde haired, blue eyed Quecks escapes and joins the Hitlerjugend, working for the Nazi party. When he returns to his neighborhood, he promotes Nazi ideology and one of his father’s Communist friends stabs Quecks to death in the street, thus making a martyr out of him.

At school, Massaquoi’s principle, Herr Wriede, an “arch-Nazi,” worked to concoct plans that would lead to “the indoctrination and recruitment of young souls to the Jungvolk.” One of those plans was that the first class to have each of the class members join the Jungvolk would get a holiday from school. Massaquoi’s homeroom teacher jumped at the idea, and “he became a veritable pitchman” trying to get his students to join. Massiquoi and most of his friends didn’t want to join, but with the pressure from Wriede, his homeroom teacher, and others, “one resister after another caved in a joined.”

When the numbers started to add up, Massaquoi’s homeroom teacher prodded the holdouts. They told him that they didn’t have anything against Hitler or the fatherland but that they didn’t really want to do the camping and other activities. To this, the teacher told them to bring their parents in for a conference, so he could try and persuade them. When Massiquoi’s turn came to speak with the teacher about his parents, the teacher told him, “That’s all right; you are exempted from the contest since you are ineligible to join the Jungvolk.” The teacher’s words shocked Massiquoi, because, as he relates, while he did not initially want to join, he was seriously contemplating membership.

After class, the teacher spoke to Massaquoi and told him, “I always thought you knew you couldn’t join the Jungvolk because you are non-Aryan. . . . You know your father is an African. Under the Nuremberg Laws, non-Aryans are not allowed to become members of the Hitler Youth movement.” To this, Massaquoi argued that was a German, but his teacher told him that while he was “a German boy,” he was not “like anybody else.” The teacher concluded by telling Massiquoi that he couldn’t do anything because “it’s the law.”

Massaquoi’s mother came to the Hitler Youth office to plead his case, even though she knew what they would say and even though she did not want him to join. They told her the same thing they told him. When she said her sonw anted to be a member, the Nazi in charge told her, “I must ask you to leave at once. . . . Since it hasn’t occurred to you by now, I have to tell you that there is no place for your son in this organization and in the Germany we are about to build.” Massaquoi, in the eyes of the law, was not a citizen, was not German.

From its early stages, as James Q. Whitman points out, the Nazi party worked to make individuals “non-citizen citizens” or second-class citizens. In fact, five of the party’s twenty five points in their 1920 program focused on citizenship. Later, in his unpublished followup to Mein Kampf, Hitler laid it all out when he wrote, “Today the right to citizenship is acquired primarily through birth inside the borders of the state. . . . A Negro who previously lived in the German protectorates and now resides in Germany can thus beget a ‘German citizen.’” The Nuremberg Laws removed citizenship from Jews, specifically, and others were also denied citizenship for being “non-Aryan.”

Massiquoi experienced this erasure firsthand as a young boy. The teacher kept track of the students in his class that joined the Jungvolk, and when every student, except for Massaquoi, signed up for membership, he declared that they achieved their “goal of one hundred percent HJ membership.” In the minds of the teacher the principal, the class met its goal. The principal even told them congratulated them and praised them because, as he said, “[you] dedicated your lives to Adolf Hitler and his vision of the Third Reich.”

However, it was not “truly” one hundred percent of students who joined. When the teacher went to the board and erased the chart, since the class reached one hundred percent, Massiquoi felt his erasure from society. He writes of that moment, “He then took a wet sponge and carefully erased the last remaining empty square, the one that represented me, thereby graphically emphasizing my own non-person status.” Added to this, Massaquoi’s class got the holiday, but since he couldn’t sign up, the principal didn’t allow him to participate, so he had to come to school. This act reiterated Massaquoi’s “non-person status” in the eyes of the state.

Like the other students, Massaquoi imbibed the indoctrination. He writes that as an eight-year old he stood in the school yard amidst adherents to Nazism, he was “filled with childlike patriotism, shielded by blissful ignorance.” Even as an Afro-German, he bought into the indoctrination, and later reevaluated his thoughts. He wanted, like every kid, to fit in, to be a part of something. Massaquoi never, like those that Kershaw mentions, fully supported the Nazis and voted for them, but growing up in that era, some of it infiltrated his psyche due to his young age.

Massaquoi is only one example I can discuss. In the next couple of posts, I’ll look at Anna Segher’s “A Man Becomes a Nazi” and Nora Krug’s exploration of her own family history and the ways that some of her ancestors, at a young age growing up in the same atmosphere as Massaquoi, bought into all of it, wholeheartedly. Until then, what are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.bsky.social.