Nora Krug begins her graphic memoir Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home with an anecdote about one of her first encounters in New York. On the rooftop of a friend’s apartment building, an elderly woman struck up a conversation with Krug, asking her where she was from. When Krug affirmed that she was from Germany, the woman began to relate “how she had survived the concentration camp” because a female guard kept her out of the “gas chamber sixteen times at the last moment.” This guard enacted “merciless violence” against everyone else, but showed compassion for the woman. The woman assumed it was because the guard had a crush on her.

While detailing the conversation, Krug inserts a page with the photographs of nine guards at a concentration camp, in rows of three. In between each row, Krug adds the following lines: “16 times on the edge of the gas chamber. 16 times escaping immediate death by a hairsbreadth. 16 times seeing others walk to their deaths while you must live.” The visages, staring out at us from the page, worked in the concentration camp, guarding women like the one Krug talked to and sending women to their deaths. They stare out of the page, looking like everyday citizens, everyday people one would pass on teh street, but we know the role they played in the genocide of millions. The question, of course, arises, “How could people commit such actions?”

Over the past few posts I’m delved into this question, first by looking at Hans Massaquoi’s internalized thoughts in his memoir then at Fritz Mueller’s descent into Nazism in Anna Seghers’ “A Man Becomes a Nazi.” Today, I want to look at the ways that Krug’s uncle, Franz-Karl, became indoctrinated into virulent ideologies, specifically through his education at school. Born in 1926, Franz-Karl experienced education under the Nazi regime and serving on the southern front in Italy where he died in battle at the age of eighteen. Krug details, through the use of Franz-Karl’s school notebooks, photographs, and more, the indoctrination he encountered as he came of age and how that indoctrination led him his beliefs.

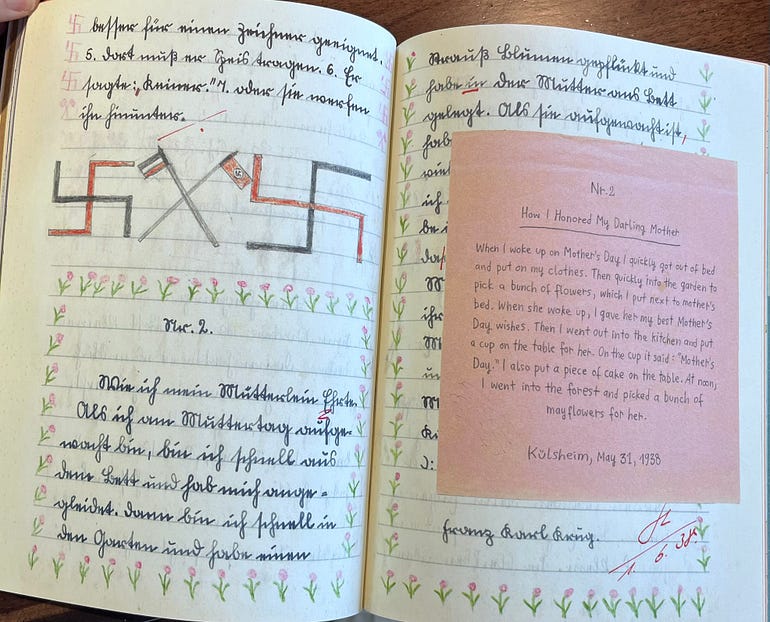

Looking through old cabinets, Krug found some “old photographs” of Franz-Karl along with “a few of his 6th-grade school exercise books.” Those books included composition exercises on everything from a maybug’s life cycle, the impact of the 30 Years’ War, the vikings, forestry, to pieces on hygeine, Hitler’s youth, and Mother’s Day. Over the course of a few pages, Krug reproduces images of Franz-Karl’s notebooks amongst photographs of Franz-Karl as a young boy and at his confirmation.

Franz-Karl’s composition on May 31, 1938, details how he picked flowers and made breakfast for his mother on Mother’s Day. The page contains Franz-Karl’s composition which he surrounded with flowers, indicating those that he picked for his mother. However, right above the composition, he drew two swastikas with the German national flag and the Nazi flag in the middle of them. As well, in the previous entry, which partly appears at the top of the page, he drew swastikas and the flags at the beginning and end of each line. Franz-Karl wrote this entry five years into Nazi rule.

Upon taking power in 1933, the Nazis established Muttertag (Mother’s Day) as a national holiday, using it as part of the “Aryan motherhood cult” that called upon women to produce more and more children for the Vaterland. Women would even receive bronze, silver, and gold medals for having four, six, or eight or more children respectively. Krug doesn’t add much more about Muttertag here, but the inclusion of this composition exercise, combined with the reproduction of the notebook itself and the photographs of Franz-Karl highlight some of the indoctrination that he experienced during his schooling.

While Franz-Karl’s Muttertag composition, apart from the images in his notebook, does not contain anything overt about Nazism or antisemitism, the second composition exercise, from January 20, 1939, details Franz-Karl’s complete indoctrination into Nazi ideology. The exercise, entitled “The Jew, a Poisonous Mushroom,” draws upon antisemitic propaganda, specifically Ernst Hiemer’s children’s book Der Giftpilz (The Poisonous Mushroom), which was distributed for free to children. The Wiener Holocaust Library notes that the book, published by Julius Streicher who also published Der Stürmer, argues that just as one has a hard time determining if a mushroom is poisonous or not an individual can find it “difficult to tell a Jew apart from a Gentile.”

Franz-Karl’s composition parrots the antisemitism of Hiemer’s book. Franz-Karl begins by writing, “When you go to the forest and you see mushrooms that look beautiful, you think that they are good. But when you eat them, they are posionous and can kill a whole family. The Jew is just like the mushroom.” After the initial paragraph, Franz-Karl writes that when seeing “the Jew from afar” he can’t recognize him, but upon speaking to the individual, he can recognize “the Jew” who could “kill a whole family” and eventually “kill a whole people.”

On the same day that Franz-Karl wrote his entry, Krug notes that Dachu’s mayor reported his town as Judenfrei, a hearing in Berlin occurred discussing the sterilization of “mentally unstable” women, Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary, “Talked things through with the Führer for 2 hours . . . He is so good and humane to me. One has to love him,” in Stalin endorsed torture. All of this happened on the same day that Franz-Karl wrote his antisemitic exercise, an exercise that his teacher gave a “B” because of some grammar and spelling mistakes.

Years later, visiting a family home, Krug’s cousin Iris shows her pictures of Franz-Karl’s teacher, Mr. Steinert. She looks at those pitcures and sees someone she did not expect. She envisoned a graying, whiskered teacher, but instead, staring back at her is a young, muscular man. In one picture, Steinart appears with his son and Franz-Karl’s sister Annemarie. In the picture, he lounges, shirtless, on the grass with the children standing behind him. Krug writes, “He is wearing a WEHRMACHT belt, and a copy of the local Nazi paper, VOLKSGEMEINSCHAFT, is lying on the grass in front of him.” Krug places this picture around the same time as Fran-Karl’s composition. Iris tells Krug that Steinert was drafted and never returned from the war. After the war, “his wife threw his golden Nazi insignia into the outhouse pit.”

Steinert taught Franz-Karl, he assigned readings and prompts for the composition exercises. Krug does not detail what Steinert taught Franz-Karl, apart from the composition exercise, but based on context clues, he indoctrinated his students into Nazi ideology and antisemitism. The photograph of him, with Annemarie and his son, shows, as well, the ways that the community accepted him. I think about this image along with one that Krug includes of her own mother from 1953 in a costume that her mother made for her. Krug’s mother stands, facing the camera, dressed as a poisonous mushroom. Krug doesn’t give any other detail except for the fact that her mother was “disappointed” because she wanted to be a princess. Krug’s inclusion of this photograph, eight years after the war, is important. Even though she does not comment on whether or not she thinks it is connected to Der Giftpilz it shows the continuation of ideas even after 1945.

In trying to find out about her uncle, Krug does not glorify him; instead, she interrogates, asking how he fell into such thoughts. Underneath a photograph of Franz-Karl with the goat he received for his First Communion around 1939, Krug points out that the Nazis “reported,” in 1936, “that 90% of all children born in 1926 had successfully been received into the Hitler Youth.” Participation, in 1939, became mandatory. She goes on to point out that Franz-Karl’s hometown of Külsheim was a place where “Jews and Christians lived side by side” for centuries. She notes that he probably knew some of “the Jewish boys and girls who lived in town.” He wrote his exercise at the age of twelve, and at that point, Krug argues, he was not old enough “to understand the power of Nazi propaganda,” but he was definitely “old enough to understand that Jews are not like poisonous mushrooms.”

Through Franz-Karl, Krug shows the ways that Nazi propaganda indoctrinated children into their antisemitic worldview, priming them to carry out atrocious and virulent acts of violence. We know that children, while they may have a thought that what teachers teach them is wrong, will still go along to get along, not pushing back against authority for fear. The longer the child goes without pushing back, even if they know something is wrong, the more susceptible they will become to buying into the ideology hook, line, and sinker, succumbing to it wholeheartedly. Krug, Seghers, and Massaquoi, amongst countless others, detail this and so much more.

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.bsky.social.