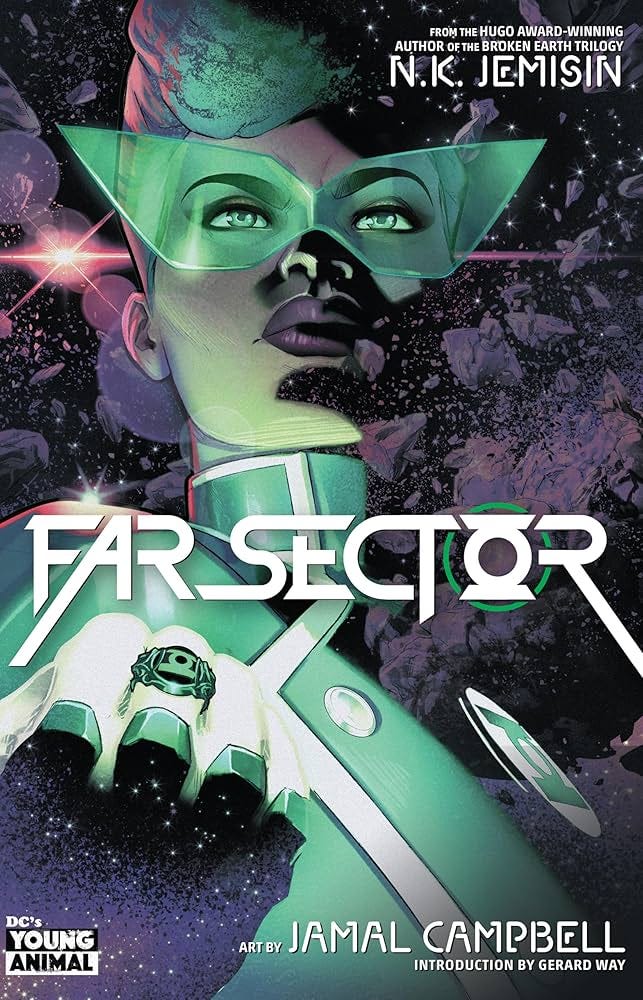

This semester, I’m teaching a Lost Voices in America literature course. I knew, from the outset, that I wanted to frame this course around noir, thrillers, and mysteries, including writers such as S.A. Cosby and Annette Clapsaddle. With that in mind, I constructed a broad course that incorporates Southern noir, Afrofuturism, mysteries, and more. I also made a point to include two graphic texts, including Pornsak Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefenkgi’s The Good Asian, a hardboiled detective story set in the 1930s, and N.K. Jemisin and Jamal Campbell’s Far Sector, an Afrofuturist text within the DC Universe. I’m also having students construct the syllabus. I’ve done this before, but it has been a few years. I’m really interested to see how the order and rationale they provide for the reading order we end up with for this class. For the assignments, I am having students do reading responses and unessay projects, things I usually do in a course like this.

Overview:

In his introduction to Pornsak Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefenkgi’s The Good Asian, David Choe discusses experiencing xenophobia growing up and the psychological impacts it had on him. He writes, “I was taught to be less than by outsiders and within my own community and my own family. Why speak up your voice does not matter.” When we think about literature, we usually think about canonical texts, those that make up what we term the “literary canon.” The American literary canon consists of those works that have been “influential” and “enduring” since their publication or afterwards. This canon arises from a myriad of spaces, including the classroom, the bookstore, the press, and beyond.

The Good Asian drew Choe in because it gave a voice to himself. It did what writers such as Ernest Gaines sought to do through his work. Scribbling in a little Steno flip notebook, Gaines wrote, early in his career, about why he became an author. He said, “Write because I must. Because there’s something out there that’s need to be said. If I don’t say it-nobody ‘else might not say it either. By this, I mean who else will write about my part of the Country? Who will talk about write about the way my people talk, the way they sing, the way they feel about God, the way they work; their superstitions. There are so many things that be said about this particular area.”

Gaines, in various interviews, details how when he moved from Louisiana to California in the late 1940s he visited the library and searched for books that depicted the people he knew from rural Louisiana. He didn’t find any works by or about African Americans in rural Louisiana, and he didn’t find any books by Black writers. Instead, he found works by Russian writers such as Ivan Turgenev and Leo Tolstoy and Irish writers, authors that wrote about peasants and people who worked the land in those countries. He found American writers who populate the American literary canon such as John Steinbeck and Willa Cather. He was drawn to all of these writers because, while they did not depict African Americans in rural Louisiana or the South, they depicted individuals who worked the land, individuals who bore resemblance, in ways, to those he knew.

These works lead Gaines to become a writer, to give voice to those he knew, those whose stories he did not see in the books he pulled off the shelves. Annette Saunooke Clapsaddle, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians did the same when she wrote Even As We Breathe, the first novel written by a member of the Eastern Band. She taught high school, and after reading the novel, one of her students, Colby Taylor, expressed his gratitude for her writing the novel and her depiction of Cowney Sequoyah. He told her, “People just don’t write about people like us.” Speaking to an interviewer, he said, “I was very, very happy to read something I could identify with almost completely.”

Using the lens of noir and thrillers, we will read Clapsaddle, Gaines, Pichetshote, and more. Each of these texts contain elements of noir literature, a genre defined by numerous characteristics including unreliable narrators, moral ambiguity, and social commentary. Megan Abbott argues that “[i]n noir, everyone is fallen, and right and wrong are not clearly defined and maybe not even attainable. While each of the works that read this semester do not fit every aspect of noir literature, they contain various characteristics that we can examine, specifically when it comes to questions of morality. These works are, as Dwight Garner says about S.A. Cosby’s work, individuals “who are after various typed of redemption.”

We will read noir in various contexts from historical fiction in Even As We Breathe and The Good Asian to Afrofuturism in N.J. Jemisin and Jamal Campbell’s Far Sector to the publishing industry in R.F. Kuang’s Yellowface to Southern noir in Ernest Gaines’ In My Father’s House and S.A. Cosby’s All the Sinners Bleed. Each of these, in their own ways, gives voice to individuals who do not have a voice within the canon. The aim is to provide you with a wide range of texts that use noir to give voice to individuals in different communities.

Primary Texts:

Clapsaddle, Annette Saunooke. Even As We Breathe

Cosby, S.A. All The Sinners Bleed

Gaines, Ernest. In My Father’s House

Jemisin, N.K. and Jamal Campbell. Far Sector

Kuang, R.F. Yellowface

Pichetshote, Pornsak and Alexandre Tefenkgi. The Good Asian

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.bsky.social.