I first read N.K. Jemisin and Jamal Campbell’s Far Sector when it came out in the trade paperback, and I’d been waiting for an opportunity to teach it. When it came out as part of DC Comics’ compact line, I knew that I would teach it in my “Lost Voices in American Literature” course. I wanted to include it in this course because it connects, in various ways, with each of the texts we read over the course of the semester. Most notably, Sojourner “Jo” Mullein, as a law enforcement officer and Green Lantern, connects with Titus Crown in S.A. Cosby’s All the Sinners Bleed and Edison Hark on Pornsak Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefengki’s The Good Asian because each of the characters must navigate being a police officer and a minority in the worlds they inhabit. This tension manifests itself in different ways in each text, and today I wanted to look at how Jo navigates it, especially in relation to to Audre Lorde’s essay “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.”

Set it the City Enduring, Far Sector focuses on Jo’s role as a Green Lantern investigating the first murder in the city in over 500 years. Following a devastating war between various groups, the City Enduring came to a consensus that would impact the entire society. They enacted an Emotion Exploit, which stripped everyone of the ability to feel emotions; however, some, rejecting the exploit, choose to take a drug called Switchoff in order to feel emotions and grapple with them. As an outsider and mediator, Jo does not have the exploit, and as such, she has her emotions. The council, which consists of representatives from the Nah, the @At, and the keh-Topi, seek to keep the populace under control with the exploit, and when individuals start to revolt and call for an end to the exploit, they crack down on them hard.

Following the murder, a protest starts with individuals who want the exploit removed and those who want to keep it. Jo, tasked with keeping the peace, intervenes, but the council still decides to strike the protestors, killing twelve of them. The Peace Division officer in charge of counetring the protest, tells Jo that the individuals “pose a threat to City peace” and that he must attack them because they, as well, “broke the law” by not having a permit. To this, Jo responds by telling him that no one deserves to die just because they didn’t get a permit. The Council authorized the strike against the protestors, and it is this action where Jo begins to think about the ways that those in power do not cede their power willingly.

Issue # 5 starts in the aftermath of the protest and the murder of twelve protestors. On the first page, after the summary of the series to that point, Jemisin includes Audre Lorde’s words: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” Lorde delivered this speech at the Second Sex Conference in New York in 1979, and a main point in her speech focuses on the fact that academic conferences, while portending to focus on bringing people together and solving problems, really only navel gaze. She points out that the conference only had two women of color, herself included, each of which the conference organizers contacted at the last minute for “diversity.” She continues by noting that when one looks at the program of the conference they would “assume that lesbian and Black women have nothing to say about existentialism, the erotic, women’s culture and silence, developing women’s theory, or heterosexuality and power.”

With all of this in mind, Lorde asks, “What does it mean when the tools of a racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy?” Essentially, how does one use the tools that the system uses to examine that same system that keeps those who examine it in subjugation? It’s the idea that many have that they can change a system from the inside, once they gain access. However, Lorde points out the fact that this method doesn’t work because the system will inevitably seek to eradicate the infiltrator at the first sign of subversion. One cannot, ultimately, use the tools of the system to dismantle that system. Lorde continues, “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master’s house as their only source of support.” Change must use different tools, and those who, through their closeness to the master’s house, will have a hard time engaging in that change.

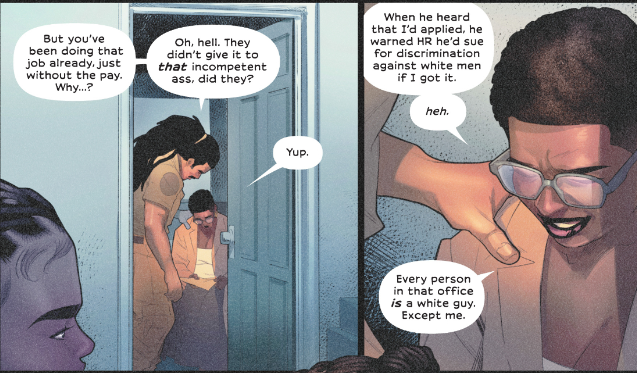

Jo’s backstory highlights Lorde’s argument. Before becoming a Green Lantern, we see Jo growing up in New York. The first flashback shows her mom coming home from work sad and angry because she didn’t get a promotion at work. The promotion, she tells her husband, went to a white man who “warned HR he’d sue for discrimination against white men if [she] got it.” The system, constructed by white men, supported her co-worker because if it didn’t support him, it would crack and start to crumble. This act, compounded by economic struggles, leads to her parent’s divorce.

Over this entire section, of seven panels, Jo narrates, “You can be hungry for more that food, see. You can have a good life, mostly, and still want better. For others, if not yourself. You can work your ass off, but still only get so far. The world isn’t fair — but you can want it to be. That’s a kind of hunger too.’ The eighth panel shows the Twin Towers on September 11, 2001, with smoke billowing into the air as Jo narrates, “Then everything changes.” Jo and her dad save victims of the attack, and this moment leads her to want to make a difference by enlisting into the military instead of going to Princeton because she sees “that the world is bigger than [her] problems.”

Jo proclaims that we “wish for heroes to make everything right,” and when those heroes don’t materialize, we seek to become those heroes, to “make things right yourself.” Jo joins the military and deploys in the War on Terror. We see four panels on her overseas either in Afghanistan or Iraq. Three panels show Jo and a young child. In the first panel, the child takes Jo to their mother. In the next panel, we see coffins being prepared for burial, with the child’s mother in one. The third panel shows Jo driving in a jeep and looking at the distraught child as she passes by. Here, Jo narrates, “But sometimes you wonder: Are you really helping? Or just making things worse?” At this moment, Jo wonders if her mission actually helps the people she has been “tasked” with helping of if she just reinforces the state’s power over individuals.

Following her service, she goes to Princeton then to the police academy, trying to find a way to make the world fair and right. Yet, that doesn’t happen. Instead, her partner beats a man with his pistol, putting him into the hospital in critical condition. Jo can’t do anything to stop the abuses of power because the “master’s tools” protect the “master’s house,” ensuring it remains standing. Jo reported her partner to administration, but it didn’t do anything and she eventually go fired, not for the report but for a social media post her friend made. On of Jo’s friends, a Black Lives Matter activist, tagged Jo in a photo on Facebook, and that photo, which was not even hers, served as a “social media policy violation,” giving the department cause to terminate her.

Jo desired to change the system from within, with the “master’s tools,” but the master would have none of it. She realizes that the system will continually work to protect itself, ensuring its survival. She realizes that in order to change the system, to make it “fair,” then one must decide what they will do to bring about that change. When talking about change, Jo asks us, “Are you gonna just go along to get along? Do what it takes to survive and nothing more? Are you okay with collateral damage, as long as you’re comfortable?” Jo interrogates us and asks us if our proximity to the “master’s house” keeps us from acting because we fear what we will lose if we choose to act. Ultimately, she asks us to think about whether or not we are more concerned with the “master’s house” than we are with our own well being.

Lorde, commenting on men asking women to educate them when men should educate themselves, points out that “[t]his is an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master’s concerns.” If we work about the “master’s house” instead of our well being or the well being of those we care about, then the “master’s house” will endure because the “master’s tools” will not be able to destroy it. When we start to imagine a better world, a better system constructed for all, not just a few, then, and only then, will the “master’s house” succumb to change. That change will not occur from within, as Jo and Lorde point out. It must come from new tools and new actions.

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.bsky.social.