Recently, I’ve started to read a good amount of 1950s era EC Comics. There, I came across the Shock SuspenStories (1952-January 1955). Shock SuspenStories was part of a larger group of books that EC’s Bill Gaines published throughout the era. The other series included Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, Weird Science, and Two-Fisted Tales. Each issue of Shock SuspenStories consisted of stories that encompassed various genres from science fiction and horror to crime and war stories making it a sort of sampler for EC Comics. Ultimately, Shock SuspenStories provided a space for creators at EC Comics to tackle issues such as racism and prejudice. The work of Al Feldstein (writer) and Wally Wood (art) serve as a good example of this moment, specifically their stories “The Guilty,” “Hate!,” and “Under Cover!”

In 1954, Gaines, on behalf of EC Comics, spoke in front of the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, a hearing that eventually led to the industry adopting the Comics Code Authority. Speaking in front of the committee about the moral messages conveyed within the dark stories between the covers of EC Comics’ series, Gaines stated,

[W]hen we write a story with a message, it is deliberately written in such a way that the message, as I say, is spelled out carefully in the captions. The preaching, if you want to cal it, is spelled out carefully in the captions, plus the fact that our readers by this time know that in each issue of Shock SuspenStories, the second of the stories will be this type of story.

Gaines’ comment is important, especially when considering stories such as “The Guilty,” “Hate!,” and “Under Cover!” These stories, all written by Feldstein and drawn by Wood directly counter racist thought and seek to convey to readers the ways that hate and prejudice affect our society.

“Hate!” originally appeared in Shock SuspenStories #5 (Oct/Nov 1952). The story depicts a group of white men in suburban America terrorizing a Jewish couple that moves into the neighborhood. The men set the couple’s house on fire, killing them. After this event, the mother of one of the perpetrators informs him that he is adopted and in fact Jewish. This causes the neighbors to begin persecuting the man’s family.

From the outset of the story, the narrative voice makes it abundantly clear that this narrative has a message. Feldstein achieves this by having the reader identify with John Smith, the man who finds out he is, in fact, adopted. Through John Smith, the narrator directly addresses the reader: “Your name is John Smith! You’re an American with a good American name! You’re a churchgoer . . . a family man . . . a respected member of your community!” In essence, Feldstein describes John Smith as the quintessential 1950s suburban American.

Continuing, the narrative voice begins to question when and where John Smith learned his vehement hate and prejudice. The narrator asks,

Did your mother teach it to you? Did your childhood friends wise you up? Did you learn it from your wife . . . your child? Did Ed, your neighbor, tip you off? When, John? When did you become infected with the disease called hate? Did your father. . . a small town doctor . . . tell you that, John? Did he list the genetic differences between you and them? Did he tell you their blood was different. . . their bones . . . their hearts?

Ultimately, the questions drive home the point that hate does not arise out of nowhere; rather, it gets passed down from generation to generation (mother, father) or it passes from neighbor to neighbor. Here, we see similarities to Solomon Northup’s discussion of the transmission of racist thought in his narrative and the ways that this transmission leads people to blindly accept the idea that they are superior to others merely based on racial or ethnic differences.

The twist, of course, in “Hate!” is nothing new as well. When John Smith finds out his true ancestry, the reader becomes part of the reveal too. The story highlights the construction of labels and identities that some use to subjugate others. The revelation of his parents’ identity causes John to sob uncontrollably and question his participation in burning his neighbors’ house. Again, the narrator poses a series of questions to the reader: “Are you different, John? Are you different, now? Do you feel any different? Do you look any different? Are you the same man you were ten minutes ago . . . watching the last wisps of smoke fade away. . . ” from the neighbors’ burned house?

Of course, the answer to these questions is “yes” and “no.” John, on the surface, is no different than he was when he terrorized his neighbors. He still has his wife and family. However, the knowledge of his Jewish ancestry does make him different from his neighbors. It also causes him to realize the ways that hate gets constructed and manipulated. Ed, the ringleader of the attack, hears John’s mother tell him the news. Upon hearing it, he turns to leave.

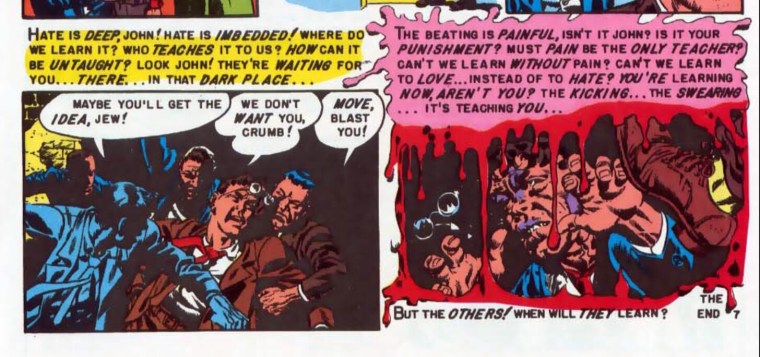

Wood’s art in the panels where John learns of his ancestry and Ed turns his back on his friend are powerful. To begin with, the word bubble where John sobs over his actions drips down the image. The panel showing Ed’s face as he leaves and John pleads with him mirrors the title page where the word “Hate!” appears in blood-red dripping down the page punctuated with splatters throughout. In this panel. the narrator tells the audience, and John, to look at Ed and see the hate in his eyes.

The next few panels show the effects of the revelation upon John and his family. Ed ignores him on the subway, Charlie crosses the street to avoid John, his son gets beaten up at school, and they receive the same letter the neighbors get at the beginning of the story. In the panel where John and his wife receive the letter, the narrator reiterates the opening page by describing John as an American: “You’re John Smith! You’re an American! How can they do this to you? How?” They do this because of the hate they have imbibed throughout their lives. That hate, for the community, becomes so entrenched and rooted within them that it engulfs them and causes them to, rather than see their error, terrorize their one-time friend.

The final two panels show Ed and others beating John to a pulp as the narrator asks how we can unteach hate? Can we? The narrator asks, “Must pain be the only teacher? Can’t we learn without pain? Can’t we learn to love . . . instead of to hate?” Can we? John learns through the pain of the kicks and punches, but his assailants do not. The narrator concludes, “When will they learn?”

The final panel shows a John’s bruised face as he has his hands to his face trying to protect himself from another kick. The narrator’s words at the top ooze down over John’s face in a blood-red color, framing the image in a grotesque manner. This panel, taken with the rest of the narrative, causes the reader to hopefully, as slave narratives and other texts before it did, to identify with John. Concluding with this image, the reader sees themselves as John and questions how they would feel if they were in the same situation.

“Hate!” calls upon the reader to question where we learn our prejudices. How do we become programmed to hate? How do we deprogram that hate? Those are questions that needed answering in the 1950s and, sadly, still need answering today. These are the morals and points that Gaines and the rest of the creators at EC Comics sought to teach its readers. They, in essence, served up didactic tales to cause readers to question their own beliefs and assumptions.

I want to continue looking at the other stories, “The Guilty” and “Under Cover!.” in the next post. Until then, what are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on Twitter at @silaslapham.

Pingback: Confronting the Reader in Feldstein and Wood’s “The Guilty!” | Interminable Rambling

Pingback: Crumbling Hate in Wallace Wood’s “Blood-Brothers” | Interminable Rambling

Pingback: Racist Thought in Al Feldstein and Joe Orlando’s “Judgement Day” | Interminable Rambling

Pingback: Reader Positioning in Al Feldstein’s “Reflections of Death” | Interminable Rambling

Pingback: American Comics: The Luxurious and Viral Commodity - Gutternaut

Grateful for sharingg this

LikeLike