Over the course of George Takei’s They Called Us Enemy, home plays an important thematic role. For Takei and his family, what does home actually mean? They live in an incarceration camp for years, and Takei, the oldest of three children, is only about five or six when they enter they camp. His siblings are younger. So, when the order comes from the camps to close in December 1944, Takei, along with others, are left thinking about home and what that word actually means for them. They have been stripped of their homes, herded up and incarcerated all over the United States, labeled as “enemy aliens.” Their property seized or stolen. Home has become, for Takei and siblings, the camps themselves, the routines, the knowledge of what will occur. Children need stability and routine, and the camps became just that.

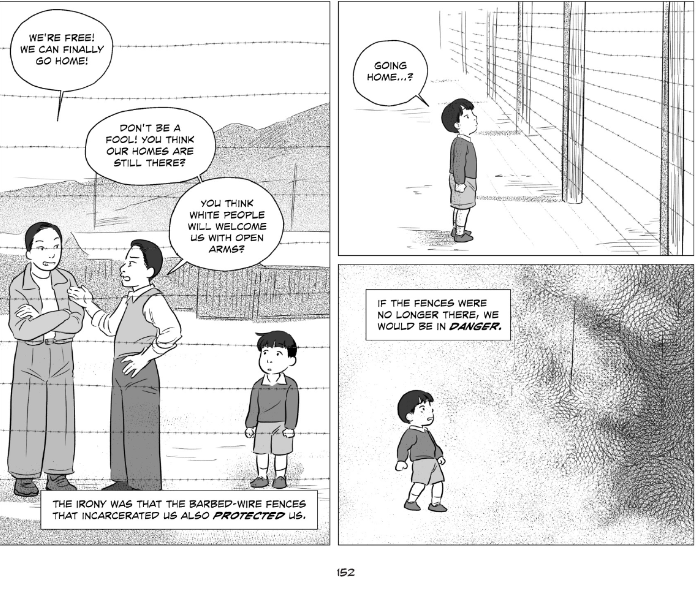

When the news comes down of the camps’ closure, Takei overhears two men talking. We see all three of them behind the barbed wire fence, us as the reader looking into the camp. The fence separates us from the men and Takei. One man says, “We’re free! We can finally go home!” His companion responds with questions: “You think our homes are still there? You think white people will welcome us with open arms?” George stares at the men with a quizzical look on his face. His narration reads, “The irony was that the barbed-wire fences that incarcerated us also protected us.”

Here, the man who asks the questions knows that even though the camp will close their houses, the ones they lived in before the war, may have been stolen. As well, he knows that white society will not accept them simply leaving the camp and moving back into their old neighborhoods. The prejudice and xenophobia remain, and the camp, for all of its harm, also serves as an insulation from these attacks. Takei stares up at the fence and asks, “Going home . . .?” The next panel shows Takei confronting not the barbed-wire fence but rather an encroaching cloud of dread as he narrates, “If the fences were no longer there, we would be in danger.” Takei feels safety, at least from the outside xenophobia, behind the barbed-wire. With that barrier removed, he thinks about what he will face once he and his family leave.

This is the same feeling that Ichiro Yamada has in John Okada’s No-No Boy. When he returns to Seattle after spending two years in a camp and two years in prison for refusing the draft, Ichiro walks down the street on a fall morning with his suitcase, and as he walks, “he felt like an intruder in a world to which he had no claim.” He feels as if he has trespassed on the street, in the neighborhood, the street and the neighborhood where he lived and grew up. He does not feel home.

When Ichiro takes his friend Kenji to a hospital in Portland, he thinks to himself as he prepares to return to Seattle, “I haven’t got a home.” He begins to question what is there for him in Seattle, a city where after the war he endures the trauma of the past few years both physically and psychologically. The effects of incarceration, in the camp and in the prison, impact him, unmooring him from his past and his sense of home. Ichiro’s feeling of loss, along with Takei’s, is not limited to the physical space of a domicile. Rather, it is a feeling of loss the extends to the nation as well. Because of the actions taken by the United States government, Ichiro does not feel at home in America, even though he was born and raised in the nation. This searching for home within a nation that rejects him and others solely based on their ethnicity, runs throughout the novel.

The final lines of No-No Boy drive home this desire to feel home, safe, and accepted: “[Ichiro] walked along, thinking, searching, thinking and probing, and, in teh darkness of the alley of the community that was a tiny bit of America, he chased that faint and elusive insinuation of promise as it continued to take shape in his mind and in heart.” Ichiro still searches for that acceptance at the end of the novel, that “elusive insinuation of promise,” that unfulfilled promise that his nation has denied him. While Ichiro is twenty-five in No-No Boy, Takei is only about six or seven in They Called Us Enemy, but he knows that he the government has taken his home in Los Angeles.

Takei’s sister Reiko, however, did not know the home in Los Angeles, even though she was born there. Rather, all she knows is the camp, the incarceration behind the barbed-wire, the routines that shape her existence. Children need routine and stability to feel safe, and amidst all of the atrocities in the camp, stability, in the form of routines, existed. When the Takeis leave the camp and move into the Alta Hotel in Los Angeles. Walking down the street, past “derelicts and drunkards,” Reiko holds her mother’s hand and stares up at her saying, “Mama, let’s go back home.” Tears fill her eyes as she pleads. Takei narrates, “Sometimes we longed for those barbed-wire fences. To us, that was home.”

At the Alta, the routines of lining up for meals and other activities evaporated, replaced with “constantly noisy surroundings with a perpetual stench.” Even while children have the ability to adapt, the upheaval had an impact, as Takei shows when he talks about walking up and down the stairs. However, the main point is that Takei and his siblings did not view the Alta as home; rather, they viewed the camp as home, a space that the government forced them into, classifying them as “enemy aliens.” It was all Takei, Reiko, and Henry knew. They adapted, becoming accustomed to the routines. Returning to Los Angeles, they are like Ichiro returning to Seattle. Things have changed. They have changed. They know that whites view them differently, as evidenced by Takei’s teacher who singles him out in class.

What is home? For Takei and Ichiro, home becomes a space of acceptance and stability, attributes that most people think of when they think of home. It is more than a physical structure. It is a psychological bond to others. This is why the sewing machine that Takei’s mother brings with her to the camp is so important. Takei thinks she has treats in the bag for him and Henry, but she has the sewing machine. She says she brought it because the kids would need clothes as they grow. The machine brings her a sense of stability, a sense of control over the uncontrollable, a way to help her family and create a home. She uses it to make drapes and other items to make the dreary conditions in the bunks look better. At the end of the book, the final image, on an all white page, is the sewing machine in the bag. It sits there reminding us that home is much more than where we grew up or where we live now. It is a feeling of connection, of stability, of acceptance.

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on Twitter at @silaslapham.