“Darling, phone call for you.”

“I’m so tired. Can you take a message?”

“It’s Martin. He wants to know if you got the card he sent last week.”

“I’ll be right there. . . . Martin, it’s so good to hear your voice. How are Coretta and the kids? . . .”

Every time I go up to the Lillian E. Smith Center, I think about the conversations that possibly too place up there, the people who sat in the chairs that I sit in, walked the grounds that I walk, pull the books down from the shelves and flip through them. I don’t know if Martin Luther King, Jr. ever made up to Clayton to see Lil and Paula. I know him and Coretta wanted to head up there to see them in 1962, and saw each other multiple times in Atlanta, with Coretta even hosting an event for the reissue of Killers of the Dream and King getting pulled over in May 1960 for driving Lil back to the hospital.

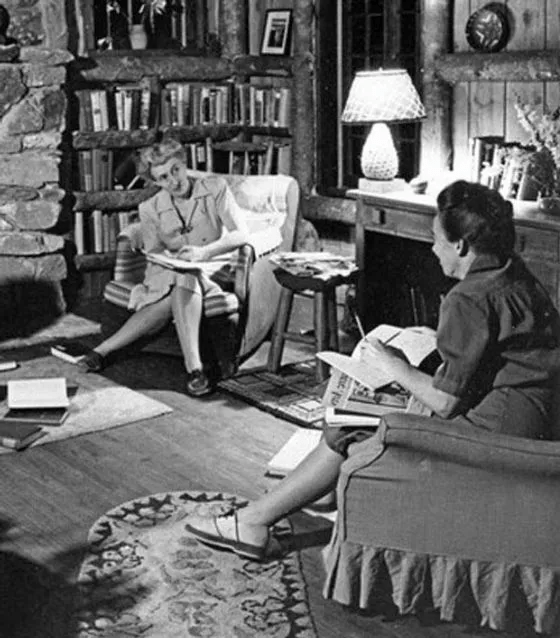

When I sit in the big common room, I imagine Lil being there, gazing out at Old Screamer Mountain when the phone rings. Paula picks it up, but Lil, due to the cancer eating away at her body, feels too tired to move from her seat. When she hears that it is King on the phone, she rises from her chair, wearily, and walks over to the kitchen where the rotary phones sits next to a notepad hanging from the wall. She may sit on a stool at the raised countertop, the phone pressed to her ear, as she chats with King about the weather, their families, the movement, or what they had for dinner last night.

When I sit in the big common room, I envision the women and men who also sat in that space, around the coffee table or the dining room table, chatting about the world. Eslanda Robeson is there, telling Lil how, before heading down to Clayton in 1943, placed copies of “An Address to White Southerners: There Are Things to Do” around Washington, D.C., in spaces where whites would find it an read it. Robeson sits next to Mary Church Terrell and Dorothy Tilly in 1943 talking about race relations and moving forward in between conversations about the war, swimming, and the weather.

I look to my left and see a young Lonnie King leaning forward in his chair in the fall of 1960. Joined by other students from Atlanta, he sits there talking with Lil about the upcoming sit ins, walking through what they plan to do at Rich’s Department store, the train station, and elsewhere. Lil offers her support and advice. All of them recognize the importance of their actions, and they plan out the SNCC meeting that will take place the weekend before the sit ins before they go to the table and partake of a meal together.

I move into the bedroom, pull Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies off the shelf, and sit down in the chair next to the bed. I see Lil standing there as I read what she marked, lines about childhood and existence. I hear her southern drawl tell me about the importance of education, the importance of always learning. I listen as she speaks as she tells me stories about the camp, the years of work she poured into the lives of the campers who came up to the mountain for the summer.

I walk back into the big common room with its large windows looking out towards Screamer Mountain. I pick up a small pinecone, made up to look like a little gnome, that served as a Christmas ornament, and suddenly I’m surrounded by children. I see a young Bill Watts there with his friends from the community. He walks up to the Christmas tree and pulls an ornament from a branch. He holds the gnome in his fingers, turning it over where he finds a quarter taped to the base. His eyes light up at the site, and he thanks Miss Lil for the gift.

A screech emanates from the mountain, and the childlike apparitions press their faces against the window to see where the sound originated. We look out and see Buss-Eye, his tail attached with a safety pin, flying towards us. He lands on the porch, and one of the children opens the door. Inside, he shakes himself clean and tells Lil that his wife, Kyta, is about to have triplets and he needs to borrow her car. If he can borrow it, he’ll make sure to leave Hershey bars on the Hershey tree for Lil and all the kids.

I see Paula, sitting across from Lil, with other people in the room. There’s a record player in the corner, and Béla Bartók’s Romanian folk dances come through the speakers. Everyone is laughing, and Paula tells Lil to stop talking. Irritated, Lil looks over at Paula then back at her interlocutors and continues. Paula again insists that Lil cease talking, Lil looks over angrily, asking why Paula insists on her silence. Paula points underneath Lil’s chair, and Lil leans down to see a snake coiled under her seat. Later, they’ll laugh, but now they work to get the snake out of the house.

I walk through the room to the kitchen, and I see Esther, Peedie, Mozelle, Lil, and Paula gathered around preparing a meal while their cocktails sit on the counter. The laugh easily at the conversation in between sips of their drinks. They assist one another in the preparation of the food. They love one another, existing together on the mountain, the world outside a distance memory as they gather and bask in each other’s presence.

I see all of this, and more, when I go to the Lillian E. Smith Center. These are things that I imagine happened in that common room. Walking elsewhere, I think about the swimming in the pool, the tennis matches on the courts, the performances in the gym, the discussions in the library, and much more. I think about the things and events we will never know about that space, the people who visited or the conversations that occurred.

Following the 1943 interracial gathering, Paula wrote to Mary Church Terrell asking that she refrain from mentioning the gathering to the press for fear of what reporters might do with the information and by extension the ways that some Southerners would use it as a tool against Lil and Paula’s work in the South. If King ever visited Screamer, we’ll probably never know, mostly due to the danger that such a visit would cause to King, Lil, Paula, and others. For most of the meetings I detail here, I’ve only found scraps of letters, here and there, referencing them. No minutes exist, and while we have recordings from the camp, we have not found any of these gatherings.

However, these gatherings took place. The Christmases took place. Buss-Eye exists. I know all of this, and when I walk through the doors of the common room, I feel it. Those memories are there, even if they are not there in the ways they actually took place. They, like Buss-Eye, exist. They must exist. They must be shared because while we do not know the extent of what happened on that mountain top, we know its importance and impact, for decades from the 1920s and well beyond Lil’s death in 1966.

When we walk through spaces, we must think about who and what came before, what happened in those spaces, and the impacts that those who gathered there had on our present. The Lillian E. Smith Center is such a living, breathing space that calls upon us to link the past to the present and the future.

If you would like to learn more about ways to donate and support the work we do at the center, please email us at lescenter@piedmont.edu.