Anne Moody ends Coming of Age in Mississippi on 1964 as she and a group of activists head to Washington D.C. to participate in a hearing about the Council of Federated Organization’s (COFO) work in Mississippi to register African Americans to vote. By this point, as Moody puts it, she had experienced both personal and national violence: “the Taplin burning, the Birmingham Church bombing, Medgar Evers’ murder, the blood gushing out of McKinley’s head, and all the other murders.” As the bus drives away, Gene asks her, “Moody, we’re gonna get things straight in Washington, huh?”

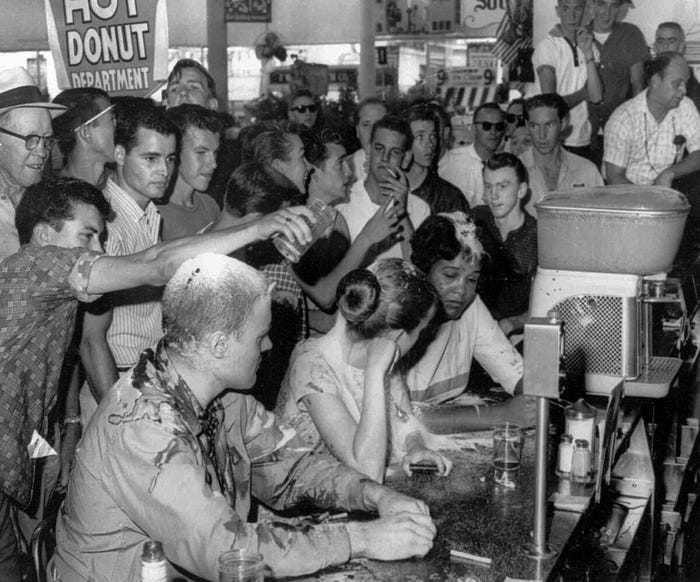

Moody doesn’t answer him. Instead, she sits in her seat and thinks to herself, “I wonder. I wonder.” With freedom songs ringing her ears, she writes the refrain of “We Shall Overcome” before ending her memoir by emphasizing her thoughts. She writes, “I WONDER. I really WONDER.” Moody’s final words, coming on the precipice of the Civil Rights Act in July 1964 and the Voting Rights Act on 1965 echo through the decades. Moody published her memoir in 1968, the year of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s and Robert F. Kennedy’s assassinations, the year of protests at the Democratic National Convention, and uprisings. Moody lived through the movement, becoming an activist after hearing about Emmett Till’s murder, participating in sit ins in Jackson while a student at Tougaloo College, working in Mississippi to register people to vote, and much more. Her actions put a bullseye on her head, and her family and friends suffered too, but she persisted, working to secure equality for all.

Moody lived through the movement, enduring physical and psychological violence, wearing herself out physically and psychologically, and feeling as if she and others would not make in progress. Attending the March on Washington for Jobs in Freedom in 1963, Moody sat in the crowd listening, and she thought, “we had ‘dreamers’ instead of leaders leading us. Just about every one of them stood up there dreaming. Martin Luther King went on and on talking about his dream. I sat there thinking that in Canton we never had time to sleep, much less dream.” The toll Moody experienced, in the face of seemingly no progress, impacted her, and it is no wonder that she thinks, as she rides the bus to the nation’s capital, if anything will ever actually change.

Four years later, King wondered the same thing. In his posthumous essay “A Testament of Hope,” he writes, “Many whites hasten to congratulate themselves on what little progress we Negroes have made. I’m sure that most whites felt with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, all race problems were automatically solved. Because most white people are so far removed from the life of the average Negro, there has been little to challenge this assumption. Yet Negroes continue to live with racism every day.” King’s comments echo, in many ways, Moody’s “I really WONDER.” He recognizes that while steps have occurred, those steps do not signify any substantial progress that rectifies over two-hundred years of oppression.

Even today I wonder what has changed. I think about a conversation I had with someone recently. The person talked about their respect and admiration for Lillian Smith but then turned around and said that Smith wouldn’t approve of things taking place today, specifically things such as Critical Race Theory (CRT). The person went out to say that CRT and things such as intersectionality were things that would destroy the West and Western ideals. The person lived through the Civil Rights Movement, even saying that they saw the Civil Rights Acts of 1964 as a crucial moment that evened the playing field, so to speak, allowing everyone to participate in the American Dream. I tried to explain that even though we don’t legally have Jim Crow or segregation directly spelled out in the law that the remnants remain and that the tactics, a legal framework, has changed to oppress individuals.

As I listened to this person, I thought about someone else I spoke with about current issues. We started talking about politics, and the person said while they didn’t like Trump and wouldn’t vote for him in a primary they would vote for him if he became the Republican nominee. I’ve known this person for a few years, and when I first met them we had a great conversation about undocumented immigrants and how their views of undocumented individuals shifted once they started volunteering and working with undocumented individuals. The person’s views shifted due to the interactions the person had with undocumented individuals, getting to know them as people, not just talking points on news broadcasts or through political rhetoric. Along with the person’s experiences with undocumented individuals, the person told me they have a queer child and they are close to individuals who have had abortions.

Conversations like the ones above left me perplexed, in many ways, because I couldn’t wrap my head around how each of these individuals could say some of the things they said and experience some of the things they experienced and buy into conspiracy theories such as the West is in decline or support policies that would target undocumented individuals, LGBTQ individuals, women, and more. I tried to parse it out, and I kept coming back, again and again, to specific things, especially after a person told me they were “fiscally conservative.” That phrase stuck out to me because it encapsulates what I often think about, how much our comfort and stability, through wealth, causes us to support interests that will maintain that above everything else.

I don’t just think it’s about power. I think it’s about stability. How many of us are willing to give up everything? I think back to Moody and the Chinn’s a wealthy and prominent Black couple who worked with Moody and others in Canton, Mississippi. At the end of Moody’s memoir, she sees C.O. Chinn walking past the jail on th chain gang. He tries to smile at her, but he can’t. Moody thinks to herself, “He had opened up Canton for the Movement. He had sacrificed and lost all he had just to get the Negroes moving.” In the span of about a year, the Chinns lost everything. The Klan put Moody on a hit list, and her family was targeted in Centreville. Yet, they persisted, working towards a society free of oppression. They gave up everything, just like Lillian Smith, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr., . . .

Just as Moody wondered whether things would improve in 1964, I sit here in 2023 and wonder the same thing. For all of the talk that things have changed, that progress has taken place, we see backlash. We see a sliding backwards. We see voting restrictions. We see lack of access to healthcare. We see the targeting of individuals based on sexuality, gender identity, nationality, and more. We see the demonization of individuals through the stoking of fires. It’s now close to sixty years since the passage of the Civil Rights Act and I hear King’s words in my head, “Many whites hasten to congratulate themselves on what little progress we Negroes have made.” I hear his words and think, that little progress is under threat. I think that and ask, “What will we do to ensure it remains and we move forward?”