Recently, I wrote about some of the ways that S.A. Cosby addresses religion and faith in his recent novel All the Sinners Bleed. Today, I want to look at another aspect of his novel that stood out to me, namely the ways that he examines the roots of enslavement and racism buried deep within the soil of Charon, the South, and the nation. He does this in various ways throughout the novel, but instead of looking at some of these numerous examples I want to zero in on the chapter where sheriff Titus Crown goes to visit Polly Anne Cunningham at Blue Hills Plantation. This chapter, more than any other section of the novel, drove home Cosby’s indebtedness to Ernest Gaines, and it caused me to think about other authors such as Frank Yerby.

The chapter opens with a description of Blue Hills Plantation. The sign on the road indicates “it had been established in 1816,” forty-five years before the start of the Civil War. Over the 200 years since its inception, the plantation survived numerous natural disasters along with the Civil War itself. Initially, the plantation produced tobacco, and that foundation allowed the Cunninghams to expand their operations into “opening a seafood factory, and later a flag factory,” this providing them with the means of constantly increasing their wealth over the generations.

Driving up to the plantation, Titus thinks about the history that Mrs. Jojo told him during Vacation Bible School. Wounded during the Civil War, Hollis Cunningham “had locked his few remaining slaves in a barn and set it on fire as the U.S. Army approached Charon.” Mrs. Jojo told Titus, “He would rather see them burn than set them free.” Titus thought to himself, “They haven’t changed much.”

After parking his car, Titus looks at Blue Hills. It appears like it is “two storms away from being decrepit,” with spindles missing from the wraparound porch, splitting and faded shutters, and plants such as hydrangeas and bougainvillea working to take over the structure. Blue Hills symbolizes the passage of time. The structure, built on the backs of the enslaved that Hollis owned, comes to represent, many ways, the decay of these foundations. However, the fact that Blue Hills remains standing, even with all of its blemishes, symbolizes that white supremacy has not ended. It remains, as if in its death throes, waiting for the final storms to remove it from the landscape.

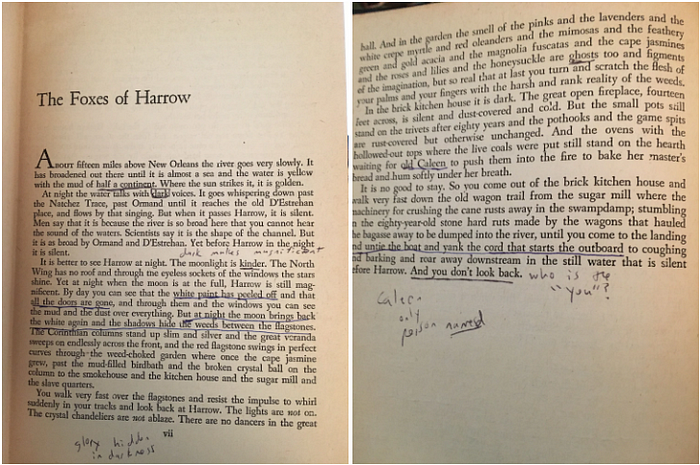

This description of Blue Hills could have made me think about the Compsons in William Faulkner’s work or Tara in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, but it doesn’t. Rather, I thought of the description of Stephen Fox’s Harrow that opens Yerby’s debut novel The Foxes of Harrow. The opening seems so out of place for a historical novel. Set in the present, the first two pages of The Foxes of Harrow put the reader in the shoes of a traveler discovering Harrow at night. There are shadows everywhere and the big house is in great disrepair. However, when the moon hits it just right, it recalls its former glory. What makes this section stand out is the fact that Yerby places the reader in the scene and also only mentions one character by name, Tante Caleen, the enslaved woman who essentially builds Harrow from the ground up.

Southern literature is full of decaying houses, representing the passage of time and the ghosts that haunt the landscape. Whenever I see one of these descriptions, I instinctively turn to Yerby’s opening because, written in the mid-twentieth century, it embodies so much of this symbolism through the description of Harrow by moonlight and the glances at former glory that fleetingly pass into the shadows. It comments on Lost Cause narratives while at the same time doing what Cosby does, pointing out the fact that progress has taken place but the foundations and roots that hinder progress remain. Until they crumble, white supremacy will stalk the land.

Polly Anne herself reminds us of this fact, and it is her story that and Titus’s conversation with her that most reminds me of Gaines’ work. Titus speaks with Polly Anne in the living room, but when I read the scene I think of it as a library. The room has “cathedral ceilings” with taxidermied animals on the walls. As well, the room is “lined with bookshelves.” The latter fact makes me think of a library, like the one where Tee Bob kills himself in Gaines’ The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman or where Marshall Hebert meets with Marcus in Of Love and Dust.

Speaking with Miss Jane about Tee Bob, Jules Rand tells her how the library suffocated his nephew. He says, “Too many books on slavery in that room; too many books on history in there. The sound of his grandfather talking to his daddy and his uncle come out every wall; the sound of all of them talking to him come from everywhere at once.” Tee Bob, surrounded by history and power, kills himself because the “rules” won’t allow him to have an intimate relationship with Mary Agnes, the Creole teacher in the quarters. In fact, he kills himself with the letter opener his grandfather used during his time in the Louisiana state legislature.

Polly Anne, in some ways, reminds me of Tee Bob. She tells Titus how she majored in history and never ascribed to the racist dogma that most of Horace’s family embraced.” She tells him about going to clubs such as “the Honey Drop and Club 24 and Gardner’s,” clubs where she could interact with people like Mrs. Jojo, Titus’ father Albert, and other members of the Black community. She recognizes her privilege, but she also knows that these spaces provide her an escape from the loneliness she feels in her marriage. Her husband Horace was gay, and they came to an understanding about their relationship, allowing each of them to see other people. Horace died of AIDS in 1988. Before Horace’s death, Polly Anne had a child with an unnamed Black man, and when it arrived, it was whisked away from the family.

Following Horace’s death, his brothers took over everything, keeping her away from the child. She tells Titus, “[T]he Cunninghams would have never allowed me to raise him” with his “white” siblings because “[t]hey considered him impure.” While Polly Anne had freedom within her marriage, she still existed, within the ritualistic rules of her society. Writing about the “race-sex-sin spiral” of white men treading into the quarters and raping Black women, Lillian Smith sums up, partly, Polly Anne’s situation when she states, “The more trails the white man made to back-yard cabins, the higher he raised his white wife on her pedestal when he returned to the big house. The higher the pedestal, the less he enjoyed her whim he had put there, for statues after all are only nice things to look at.” Granted Polly Anne’s situation is different, but the society of Charon would not recognize this fact.

Likewise, Polly Anne reminds me of characters such as Jack Marshall in Gaines’ A Gathering of Old Men or Frank Laurent in Gaines’ short story “Bloodline.” Each of these white men realize the problems with the “rules,” and each, instead of doing something to change the “rules” decides to kick the problem down the road. Marshall drowns himself in alchol and Laurent just places the burden on subsequent generations. Polly Anne, in a similar manner, refuses to change the “rules.” Instead of standing up the Cunninghams, she acquiesces and allows them to dictate what happens with her son.

There is so much more I could say about this scene, but I don’t want to give too much away. What are your thoughts? Please let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.