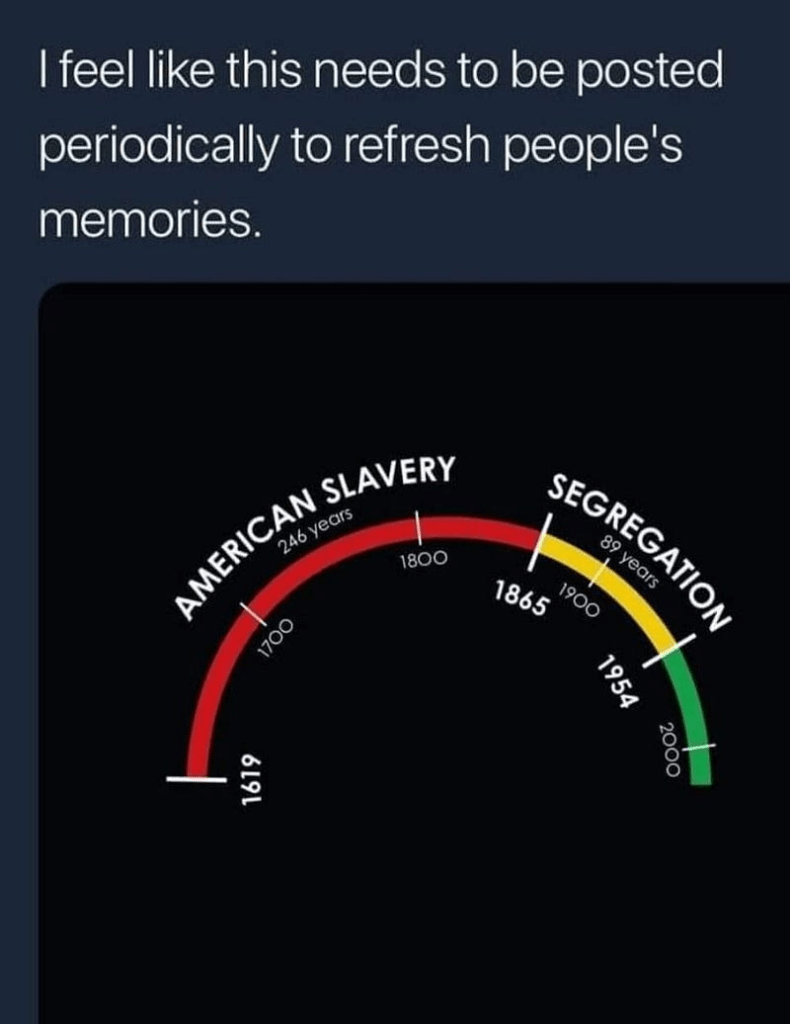

Over the past week or so, I have seen multiple people on my social media feeds post this timeline. I don’t know who originated it, or who wrote it. However, I do know that almost every semester I construct my own timeline and break it down in class, usually going back to the end of the Civil War. When doing this, I break it down by familial generations, tracing backwards to show students that we are not far removed from these moments in history. In doing this, I strive to show them that while we may have “legally” ended Jim Crow and “overt” legalized segregation, the roots of those institutions remain because people who were alive during that period and supported those institutions didn’t necessary relinquish their beliefs when the laws changed and they continue to pass those beliefs down to their subsequent generations.

When I walk students through this timeline, I use myself as an example, telling them I was born a decade after Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination in 1968, what many see as the end of the Civil Rights Movement (1954–1968). I tell them that my parents were born in 1951, right before the “start” of the Civil Rights Movement with the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. That means that their grandparents, along with my parents and grandparents, lived through the Civil Rights Movement. That means that they are only two generations removed from the movement. That means that their family members experienced it and probably had feelings about it.

If we go a little further back, I tell them my grandparents were born in the early 1900s, meaning they lived through the Great Depression and World War II. That’s only three generations removed from them. My great grandfather on my dad’s side was born in 1893 and served during World War I. My great-great grandfather was born in 1866, right after the Civil War, and my great-great-great grandfather, Jacob, was born in Germany in 1821, immigrated to the United States and settled in Louisiana. He was a Confederate soldier during the Civil War, serving in 8th Regiment Louisiana Minden Blues. He took part in the Battle of Manassas, was captured at the Battle of Antietam. That means I am only five generations removed from a family member who fought for the Confederate States of America, making my children and students only six generations removed.

That is not a long time. If we look at it in years, Jacob was born a little over 200 years ago and he is only five generations removed from me. In the grand scheme of human history, 200 years is a drop in the bucket, a fleeting period. The United States only celebrated its 200th birthday in 1976. 2026 will mark our nation’s 250th anniversary. Again, that is not an extensive period of time. If we extrapolate that out, keeping the six generation remove, we are a mere twelve generations removed from 1619, the arrival of the first enslaved individuals in what would become the United States.

Thinking about history in this manner condenses it, pointing out that even as we move through time, measuring the progression in years, decades, and centuries, those larger numbers eclipse the fact that only four people (my dad, grandfather, great-grandfather, and great-great-grandfather) stand between me in 2024 and the Civil War, enslavement, and more. Only one link exists between myself and the Civil Rights Movement. That is not a lot. In fact, it reinforces my statement earlier that even as we see national progress and legislation we also see the continuation of vile ideas of white supremacy and oppression that birthed the Civil War, Jim Crow, and much, much more.

This is partly what I think about when we face legislation that seeks to limit the history teachers can teach in school. It’s what I think about when I see people arguing to ban books. It’s what I think about when I see proposals to round up immigrants, hold them in concentration camps, then deport them. It’s what I think about when I see so many things happening today. I think to myself, we’re not far removed. We may have progressed some but we haven’t come close to eradicating the virus infecting our very beings. It flows through our veins, passed down generation after generation after generation, whether consciously or unconsciously. We live with it. We can mediate it, we can attempt to cure it in ourselves, but we can’t eradicate it until we reckon with the fact that that the issues we face are not new and were not solved in the past.

In “The Propaganda of History,” W.E.B. DuBois writes that “somebody in each must make clear the facts with utter disregard to his own and desire and belief.” We must lay the facts bare, not sugarcoat them with palatable myths that take the place of reality. DuBois continues, “One is astonished in the study of history at the recurrence of the idea that evil be forgotten, distorted, skimmed over.” We must remember it all, no matter how painful because when we fail to do so “history loses its value as an incentive and example; it paints perfect men and noble nations, but it does not tell the truth.”

The truth gets subsumed. It gets sticky and sweet, pleasing to our taste buds as we put it on our tongue and move it around in our mouth. We taste sweetness, not the sourness of truth. We pat ourselves on the back. We say, “Racism has ended.” Or, we say that we would have done something in the face of white supremacy or anti-Semitism and been on the right side of history. We say, “If I was there I would have marched with King. If I was there I would have saves Jews in Europe.” It makes us feel better. Removed from the event, even by one link, we savor the sweetness, making ourselves part of the narrative.

Yet, we need the sour taste to counteract the sweet. We need the first sour taste of a Sour Patch Kid followed by the sweetness. The sour makes the way for the sweetness. They can exist in tandem, working together to present the palate with a complete picture. As James Baldwin so aptly put it, “I love America more than any other country in the world and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” The United States provides us with the ability to have the sweet and the sour together, reveling in the joyous while also confronting the despicable.

When we recognize that our past is not as past as we think, maybe we will stop congratulating ourselves to make ourselves feel better and feel like we’re on the right side of history and instead act to bring to fruition the dreams of that past that create a more equitable and just society for all. We must not be like those who Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote about in “A Testament of Hope” who congratulated themselves after the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and said white supremacy is gone. No, as King writes, “Many whites hasten to congratulate themselves on what little progress we Negroes have made. I’m sure that most whites felt with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, all race problems were automatically solved. Because most white people are so far removed from the life of the average Negro, there has been little to challenge this assumption. Yet Negroes continue to live with racism every day.”

I am two links removed from King. He was born between my grandparents and parents. Our children are three links removed. His words remind us that even with legislation and mass movements things remain the same, just under a different guise. He reminds us that the past is not as far removed as we want to think it is. It is present all around us in people we know and interact with everyday. Ruby Bridges is still alive. She is younger than my parents. Jerry Jones is still alive, and he was in the white crowd that tried to bar entrance to North Little Rock High of African American students in 1957.

Always remember, as William Faulkner put it, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”