Writing about how their time in Washington D.C. and at Howard University drew to a close in the early 1940s, Pauli Murray reflected on all the work they did, notably the 1943 sit-ins in the nation’s capital and how those sit-ins laid the foundations for the 1960s. Murray thinks about the tensions between their “urge toward kamikaze defiance of Jim Crow and the more demanding discipline of prodding research” to counter Jim Crow. This tension led Murray to think about the long path forward, one that stretched back before their appearance in the world in 1910 and after their physical passing in 1985. Murray saw themselves as part of a long relay, one leg in the race for equity, equality, and freedom.

In Song in a Weary Throat, Murray writes about coming to a balance between the tensions they faced. Murray says, “In the process I discovered that joining others in the effort to overturn an entrenched system of injustice is often like running a relay. There were times when I didn’t even know the outcome of the race, other times it was my privilege to break the ribbon at the finish line, and still others when I share an overwhelming sense of accomplishment and exhilaration even though my contribution had been made early in the contest, not at its culmination.” Murray knows that they play a small part in a much larger and longer race, one that has people come and go from the stage while their presence remains ever present after their physical passing.

Murray notes that during their work they experienced “moments of deep despair,” but they countered those moments by maintaining “the sustaining knowledge that the quest for human dignity is part of a continuous movement through time and history linked to a higher force,” whatever that force may be. Describing the Montgomery Bus Boycott’s in Stride Toward Freedom, Martin Luther King, Jr. noted that his adherence to nonviolence stemmed partly from his belief “that the universe is on the side of justice” and that “the nonviolent resister” feels confident in their position because they know that they have “cosmic companionship” in their “struggle for justice.” This “cosmic companionship” stems from a higher entity and also from those who came before, those who worked together to lay the foundations for “a harmonious whole.”

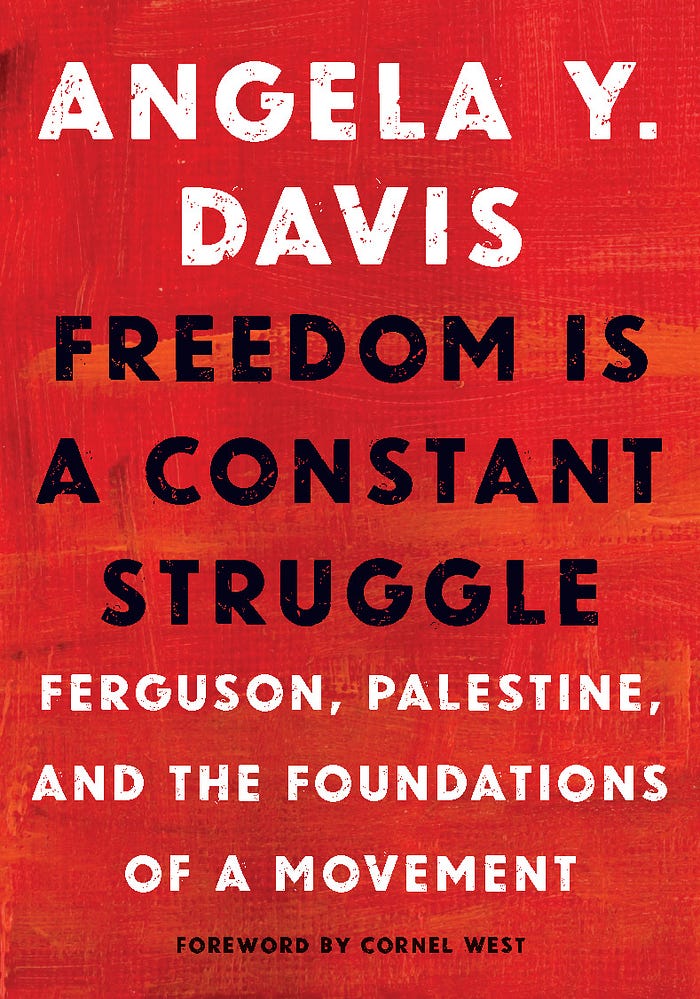

King didn’t start the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Rosa Parks didn’t start the Montgomery Bus Boycott. It was a collective moment within Montgomery that had tendrils stretching backwards to Pauli Murray and further. They stood on the cosmic foundations of those who came before, learning from them and building upon them. As Angela Davis asks us, “I wonder, will we ever truly recognize the collective subject of history that was itself produced by radical organizing?” She asks specifically about the history of organizations such as the Southern Negro Youth Conference and their work.

Davis continues by asking us to think about how we can dismantle the individualistic narratives we tell ourselves about the past, narratives that impact how we think about ourselves in the current moment and the future. Davis asks, “How can we counteract the representation of historical agents as powerful individuals, powerful male individuals, in order to reveal the part played, for example, by black women domestic workers in the Black Freedom Movement?” She points out that we don’t know the names of all of the Black women who participated in the boycott, but “we should at least acknowledge their collective accomplishment” and role within the boycott and the movement.

Murray, King, and Davis all point to the “cosmic companionship” we inhabit in this world. The companionship that incorporates the past, the present, and the future, putting us in contact with those beyond ourselves. To progress forward, to create “a harmonious whole,” the “beloved community,” we must embrace our companionship with those we will never meet. We must look past our individualistic selves, beyond the two dates etched into our tombstones. We must recognize that we are but one leg in a long relay, but one participant in a never-ending conversation, but one link in an infinite chain of history.

Each of these activists and more thought beyond themselves, they did what Davis called upon us to do when she said, “it’s important for us to think forward and to imagine future history in a way that is not restrained by our own lifetimes.” Too many of us think about what we can accomplish while alive, what we can acquire, what we can achieve. We may think about what we want to pass on to those close to us, thinking about their future, but we tend to keep our thoughts individualistic, not looking beyond ourselves or a small, select group. We think, as Davis puts it, “well, if [progress] takes that long, I’ll be dead. So what? Everybody dies, right?”

What if Thomas Jefferson, David Walker, Frederick Douglass, Ida B. Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Lillian Smith, Pauli Murray, Martin Luther King, Jr. thought this? What if each of them said, “I don’t care what happens when I die. I’ll be dead so it won’t affect me”? Where would we be? We must think about the relay, the passing of the baton from one generation to the next, the “cosmic companionship” we share with those who came before and those who will follow after us. We must move past the individual and remember that individuals didn’t make history, collectives did, and individuals don’t create the future, collectives do.

Davis stresses that we need to think about the collective not the individual. When we focus on individuals we flatten reality. We make it palatable, scrubbing the collective out of the image. We forget about Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, Addie Mae Collins, and Denise McNair; we forget about the Children’s Campaign and Bull Connor siccing law enforcement and firefighters on kids with dogs and firehouses; we forget about so many people and events. “All of this,” as Davis says, “gets erased when you obsessively focus on single individuals.”

Focusing on individuals makes it easier to whitewash the narrative too, making it palatable for the masses. We see this with King. People are quick to point to his dream but shy away from his comments on police brutality or his comments on capitalism, which were formulating early, as he shows in Stride to Freedom. We must think beyond indivduals and beyond ourselves. We must look forward, thinking about those who will come after us, the world we will leave them. We cannot continually kick the can down the road hoping some future generation will solve the problems we face. We must solve the problems ourselves so future generations will have a better life, a better existence to achieve “”a harmonious whole” where they can live and love and be one with themselves, each other, and the world.

What are your thoughts? Let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.