During my educational career, I sat in countless classroom regurgitating information back to the one at the head of the classroom who held my grades and my future in their hands. I felt, for the most part, disconnected from any of my experiences or reality. That does not mean that the information I learned did not relate to my life; it just means that the holders of my future never truly made those connections clear. This “banking” of education, as Paulo Freire calls it, made it hard for me to think about the information I learned in one class in relation to another class, let alone in relation to my own life outside of the walls that kept me ensnared for the majority of the day.

The depositing of information into my brain didn’t benefit me in any way, except for adding to my vast trivia knowledge that I always hoped to parlay into a game show appearance. At its base level, this banking only served to reinforce the structures and positions of those who held my future in their hands, thus causing me to comply to their whims and their positions in order to have any chance at success. Freire writes, “In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing.” Thus, they feel as if those who enter their classrooms do not have any knowledge of anything whatsoever and must be filled with the “correct” knowledge.

The more deposits that enter the student’s head, the more the students becomes one of the “adaptable, manageable beings” that will not question any of the information or systems deposited into their very being. In order to break free of this system, Freire notes that we must develop within ourselves a “critical consciousness which would result from [our] intervention in the world as transformers of that world.” Our development of “critical consciousness” allows us to imagine that new world, to transform the current world into a space that includes not just ourselves but those around us as well.

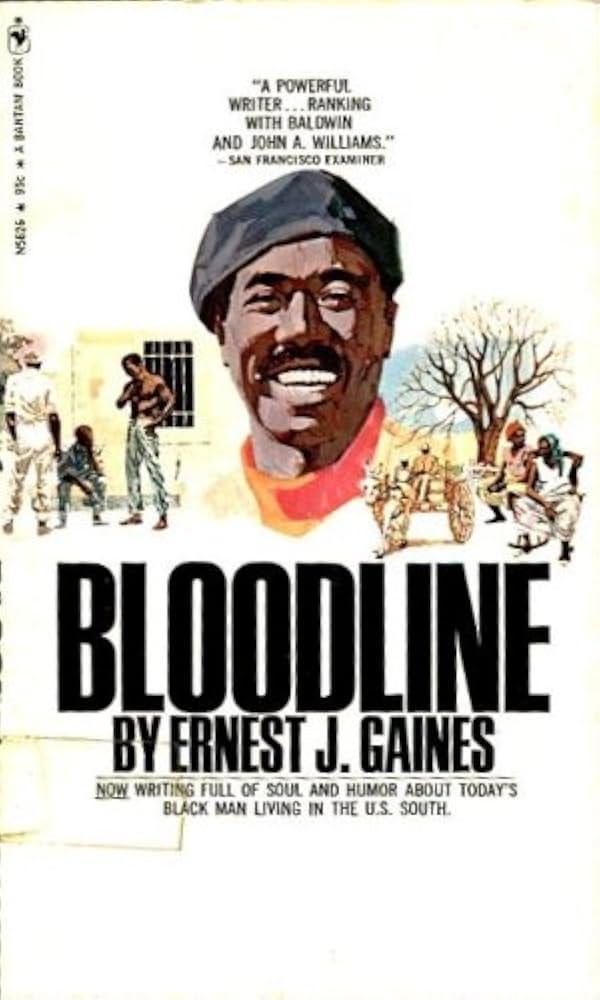

As I reread Ernest Gaines’ short story collection Bloodline, I kept thinking about Friere and educators such as Nadezhda Krupskaya and Ta-Nehisi Coates, especially in the ways that they discuss the liberatory nature of education to move individuals and communities forward to transform the world. Education plays a prominent role throughout Gaines’ ouvere, and especially in the first two stories in Bloodline: “A Long Day in November” and “The Sky is Gray.” In “A Long Day in November,” Sonny, the young narrator of the story, goes to school and pees his pants because when his teacher asks him to recite his lesson he can’t because his parents, who constantly work, did not have time to teach him his lesson. Sonny is learning to read, using a reader in the class, so he is not necessarily “banking” facts and knowledge, but he is in a situation where he will only go to school a few months out of the year, when he’s not working in the fields, and will learn what those in power want him to learn so that he will remain malleable to them.

The eight-year-old James, in “The Sky is Gray,” also experiences education in a similar manner. He has to miss school to go to Bayonne and get his tooth pulled, and while walking through the frigid streets with his mother, he thinks about what his classmates do at school. He says, “I ain’t been to school in so long — this bad weather — I reckon they passed [Poe’s] ‘Annabel Lee’ by now. But passed it or not, I’m sure Miss Walker go’n make me recite it when I get there.” Like Sonny, James must recite something back to his teacher, in this case Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee.” Instead of reciting a poem by Claude McKay, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, or Countee Cullen, he must recite Poe, thus placing Poe above Black poets whom he may speak to his own experience and still use the same style and techniques as Poe. Again, this is a manner of maintaining power because Poe becomes the standard, not McKay, Dunbar-Nelson, Cullen, or others.

When James and his mother sit in the waiting room at the dentist’s office, they encounter a young, Black man who is a student or a teacher and who embodies Freire’s “critical consciousness,” moving beyond the banking system and engaging with knowledge in a way that will provide him and others with the tools to become “transformers” of the world. The student highlights this specifically through his interactions with the minister in the waiting because the minister represents the “banking” system, the system where the student merely needs to recite the poem and regurgitate the facts in order to “succeed” under oppression or to have a modicum of perceived “freedom.”

Sitting in the waiting room, the young, Black man listens to the preacher talk about how it is not anyone’s place to question God’s plan. The young man challenges the preacher and says that the problem comes down to not questioning. He tells those in the room, “We should question and question and question — question everything.” Instead of taking things at face value, or because someone at the head of the class tells us to, we need to question, we need to critically engage and think about what we learn. When we don’t do this, we become merely receptacles for deposits of knowledge that do no acrue interest over time because the deposits don’t work for us. Instead, they remain locked away in the bank, out of circulation.

The preacher gets angry and accosts the young man, claiming that the man is angry because his parents died and that the collective community sent the man to school to learn, not to question. To this, the man responds, “I’m not mad at the world. I’m questioning the world. I’m questioning it with cold logic, sir. What do words liek Freedom, Liberty, God, White, Colored mean? I want to know. That’s what you are sending us to school for, to read and to ask questions.” The preacher sees education as banking, not as critical consciousness, and the man tells him that education should be critical consciousness, a means of questioning and transforming the world.

The man tells the preacher that his sorrow for the man arises because the man challenges the preacher’s positions. He says to the preacher, “You’re sorry for me because I rock that pillar you’re leaning on.” The preacher is “sorrowful” because the man does not adhere to the gifts that the powerful bestow upon him, unlike the preacher who takes the gifts and keeps bowing and scraping to the whites in order to make anything for himself and his family, not questioning the system that keeps him oppressed.

The preacher gets so angry that he slaps the man and leaves, and once he leaves, others in the waiting room start to talk to him, trying to get him to explain some more of his views. The conversation starts to center on words and the meaning of words, all of which the man says, “mean nothing.” He tells them, “Words mean nothing. Action is the only thing. Doing. That’s the only thing.” When one merely banks knowledge, the doing never occurs. Instead, complacency sets in, and action fails to take shape. The questioning of information, of what one learns, leads to action because the questioning moves past the bestowal of gifts to the interrogation of those gifts and what they actually mean.

The man questions those around him about words. Someone asks him what color the grass is or the wind. He tells them that grass is black and wind is pink. Those gathered in the room scoff at him, but he retorts, “You don’t know it’s green. . . . You believe it’s green because someone told you it was green. If someone told you it was black you’d believe it was black.” The man sums up, in this moment, the importance of questioning and of critical consciousness. Knowledge exists, partly, on consensus. We have a consensus that grass is green, but the man’s point holds because he is trying to get those around him to actually think about why the grass is green.

James sees the man and listens to him with rapt attention. He tells us, “When I grow up I want be just like him. I want clothes like that and I want keep a book with me, too.” Rather than merely reciting “Annabel Lee,” James wants to question it, to critically examine it, to take what he learns and apply it to the world around him, hopefully transforming him. James sees the man, not the preacher, as a role model because the man represents what could be, what should be, the action that must occur. The man embodies Freire’s pedagogy, questioning the knowledge around him.

What are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.