Every now and then, I get to the point where I’m not sure what I want to read. When that happens, I go to my bookshelves and start to browse, pulling down a book, reading the description and the first page, then returning the book until I come upon one that I want to read. This process is how I came to read Helen Weinzweig’s Basic Black with Pearls, a book that a friend gave me a while back. Weinzweig’s novel sucked me in from the start because I wasn’t sure exactly what to expect. Sarah Weinmen calls Basic Black with Pearls an “interior feminist espionage novel,” and that really describes the novel because it is a work that deals with the interiority of Shirley Kaszenbowski and her existence as an “invisible woman” due to her age and class.

Weinmen mentions that Basic Black with Pearls contains references to Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper, and Virginia Woolf’s work, among others, and we can read Weinzweig’s novel in relation to these texts. As I read the novel, I thought about Chopin, Gilman, and Woolf, but I also kept thinking about novels such as Anna Seghers’ Transit, not in relation to gender but in relation to the ways that Toronto works as a character in Weinzweig’s novel like Marseille does in Seghers’ novel; I thought about Judy Blume’s Wifey because of the connections between Sandy Pressman Shirley; I thought about Magda Szabó’s The Fawn because the novel follows Eszter Ency throughout one day, moving back in time to talk about her life. Each of these works, except for Transit, focus, as well, on the interiority of the female characters and the ways they navigate a patriarchal society that places them into specific molds of existence. At some point, I could foresee teaching all of these novels in a course, looking at them in relation to other feminist novels.

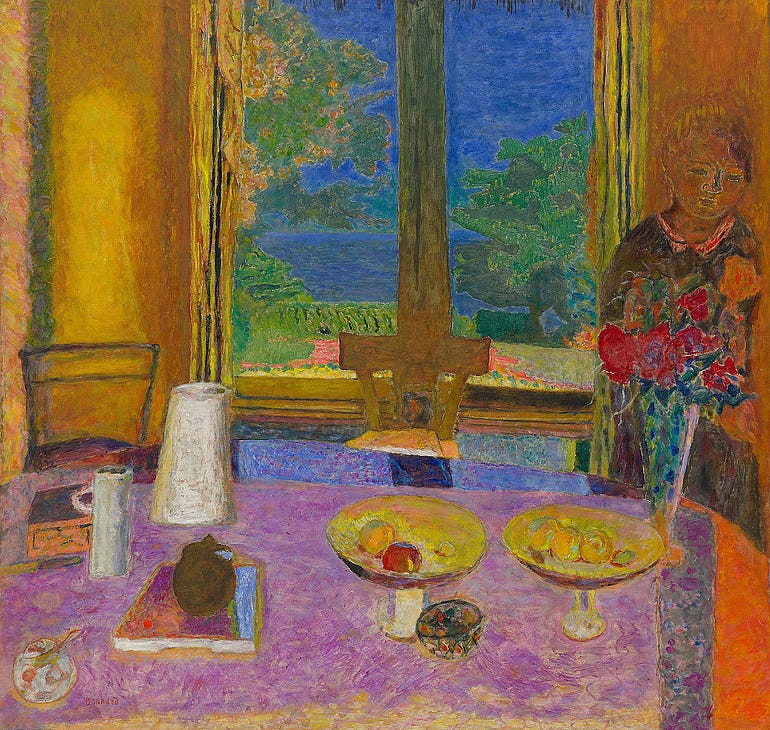

While I could discuss numerous aspects of Basic Black with Pearls here, I want to focus on one specific scene where Shirley goes to the Art Gallery of Ontario and sees Pierre Bonnard’s Dining Room on the Garden and becomes so enraptured with it “that she,” as Weinmen states, “enters into communion with its pained female subject,” conversing with the individual in the painting. As Shirley looks at the painting, she sees the the cloth on the table, the bowls, the cups, and the reflection of the sun. Moving her eyes along the image to the right of the canvas, Shirley spots “a wraith-like form, barely discernible in the right-hand corner beside the window.” The form stands there, “painted into the background” as she stares back at Shirley her averted eyes and pain-tightened mouth.

The teenager girl, blending in with the wall in the image, calls out to Shirley for help to escape her father who has imprisoned her. Shirley views herself in Bonnard’s painting, and flings open the windows, telling the girl to escape towards the horizon, but the girl responds, “There is nothing beyond this painted room. No sky, no trees, no garden. Oh these artists and their tricks! They deal in illusion: everything is a matter of perspective.” Nothing exists outside of the frame but a “twelve-foot stone wall around the yard” without a gate. The girl stands imprisoned in a scene of light and seeming comfort, without any hope of escaping her gilded cage.

The girl tells Shirley that she ended up in the room because her mother, who could not support her, sent her to live with her father because, since he lived in Antibes, her mother thought he had money. He didn’t. The father viewed the girl angrily, and when the girl went to a dance with Emil, a boy she saw at a hotel, her father locked her in the room, forcing her to subsist on nothing “but dry crusts of bread” and “coffee made with chicory.” Everything else in the room that appears to be sustenance, the girl tells Shirley, “has all been created for effect.”

The father accuses the girl of having sex with Emil and getting pregnant. He compare the girl to who her mother, who was the girl’s age when she conceived the girl. The father called a doctor to the house, and when they tried to get her “to lie down and spread [her] legs,” she refused. They persisted and ended up holding her down and drugging her, causing her to lose consciousness. When she came too, the doctor had left and she felt nauseous and sore. Her father then locked her in the room and told her she would stay there until her mother sent money or he found a man “to pay a handsome price for [her] virginal favors.” The father controls the girl, locking her away in a gilded cage of light and beauty, an illusory room where she hides in the wall.

Once the girl “retreated to her corner and faded back into the wall,” Shirley thinks in Emil escaped the Nazis and what happened to the girl. She stands in front of the painting and sees “two policemen.” She approaches them and tells them about the girl, but they view her as mad, taking her by the arms and escorting her out of the gallery. In this moment, Shirley reminds me of the woman in Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper” or of Edna Pontellier in Chopin’s The Awakening. The patriarchal idea of womanhood ensconces her, and even though she can move freely throughout the world she is trapped within a gilded cage of her own imagination where she seeks to escape the trappings of domesticity through her clandestine liaisons with Coenraad. As Weinman puts it when talking about the antecedents for Basic Black with Pearls, “These novels describe women not only breaking away from conventions but filled with desire and ambition that are almost too much to bear, a secret from themselves.”

Throughout Basic Black with Pearls, Shirley travels throughout Toronto, escaping her domestic life with Zbigniew and her children through her exploits with Coneraad. Of Zbiginew, she says he did nothing wrong, but she had to find out about herself, who she actually is as a person. She feels trapped, like Sandy in Blume’s Wifey or Edna. She feels like the girl pressed upon against the wall, blending into the wallpaper, disappearing from the canvas. She must escape, even if that escape is in her mind. She does this through Coneraad, and the girl in Bonnard’s painting reminds her so much of herself that she must figure out a way to remove her own self from the gilded cage.

I am really interested in teaching Basic Black with Pearls at some point alongside Slimani, Chopin, Perkins, and others. Stay tuned for a possible syllabus that incorporates these texts. Until then, what are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.