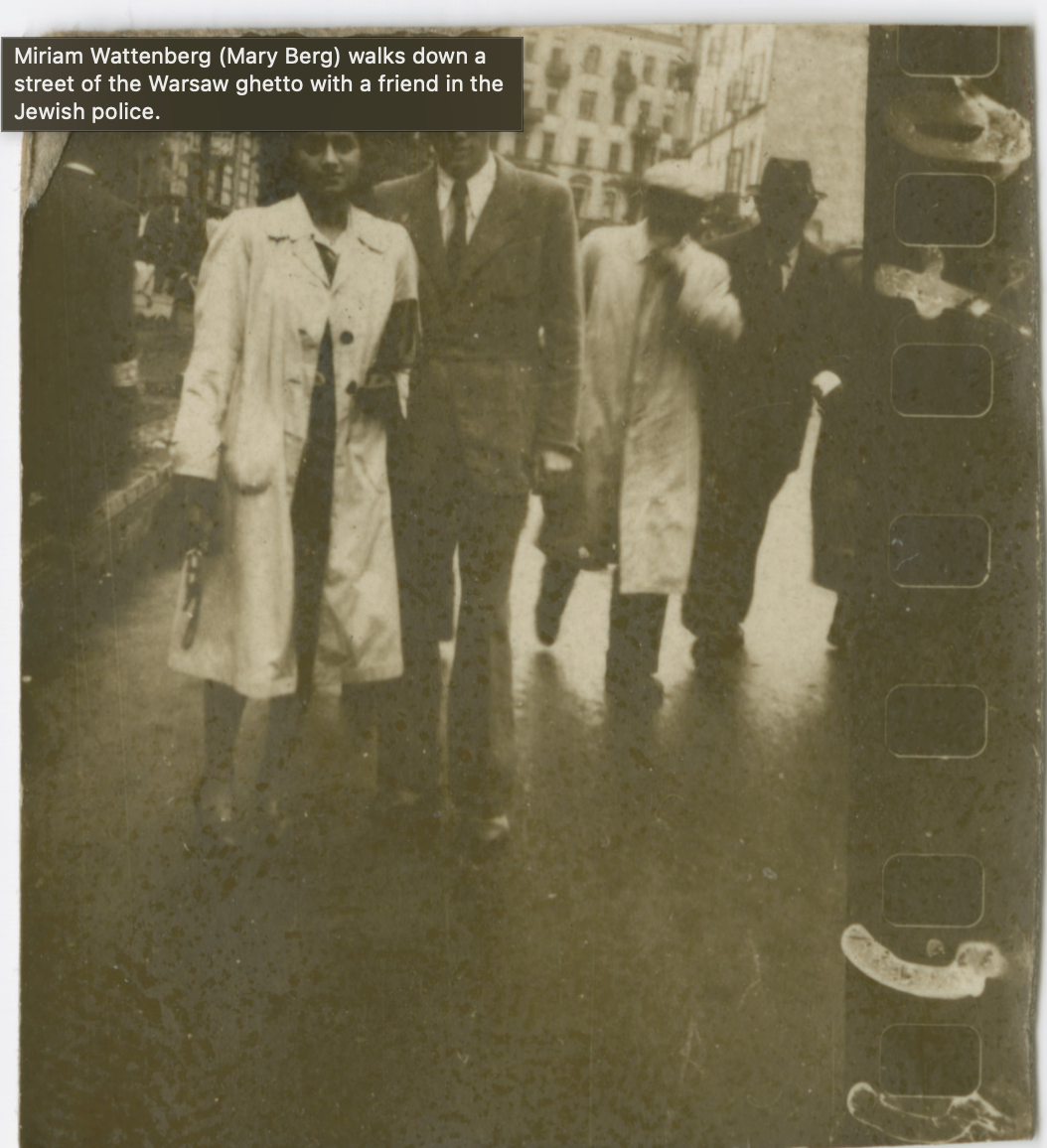

Over the past few weeks, I’ve read Hans Massaquoi’s Destined to Witness: Growing Up Black in Nazi Germany and Mary Berg’s diary that she wrote during World War II, specifically living and growing up in the Warsaw Ghetto before her family’s escape to the United States in March 1944. Massaquoi’s memoir didn’t appear until 1999, and he wrote it looking backwards, after individuals suggested he document his experiences of the son of a Liberian man and a German woman growing up under the Nazi regeime and during the war. Berg, on the other hand, chronicled her experiences in real time, laying bare her fears and hopes in the face of death and oppression. Both are important historical works that broaden our understanding of Nazi ideology and violence and the ways that individuals fought to survive.

As I read Berg’s diary, multiple thoughts kept coming to mind, from the horrors in her descriptions of blood running through the streets and murders outside her window to her pleas for those in the United States and elsewhere to see the horrors and save them from the Nazis. However, the main thing that stood out was the ways that Berg describes life in the Ghetto, in Pawiak, and elsewhere. Amidst all of the violence and oppression, life continues. She attends school. She forms a theater troupe with some friends and they perform in the Ghetto. She sunbathes. She plants a garden. She lives. She forms community, an important counter to state oppression.

Along with these moments, Berg constantly comments on the beauty of the world in the face of so much tragedy. She describes the beauty of a blue sky right before the horrors of a random act of violence from a Nazi against a Jewish individual. In these moments, she reminds me of Solomon Northup who, amidst his violent descriptions of enslavement, provides readers with images of beauty in the landscape of Louisiana in juxtaposition to the brutality inflicted upon him and others. These moments serve as rebellion against the violence and brutality. They serve as reminders of the beauty in this world, even in the face of destruction. They serve as a means of hope for the future, beyond the acts of terrorism.

Over the course of her diary, Berg points out ways that individuals resisted. She describes how humor, amidst the typhus outbreaks in 1941, served as “our only weapon in the ghetto — our people laugh at death and at the Nazi decree. Humor is the only thing the Nazis cannot understand.” Likewise, the longing for beauty and the descriptions of beauty counter the Nazi ideology and actions because they highlight hope. After describing the murders of over sixty individuals connected with the underground, Berg writes a detailed paragraph about the beauty of the little garden her and her family planted in the courtyard.

In our garden everything is green. The young onions are shooting up. We have eaten our first radishes. The tomato plants spread proudly in the sun. The weather is magnificent. The greens and the sun remind us of the beauty of nature that we are forbidden to enjoy. A little garden like ours is therefore very dear to us. The spring this year is extraordinary. A little lilac bush under our window is in full bloom.

Berg’s description of the garden serves as a weapon, even if it is only for herself, against the Nazis. She writes that the scene reminds her of the beauty that the Nazi forbid her and others to enjoy. It reminds her of their humanity and their individuality, their very existence, and it points the way towards their freedom, even if that freedom may not be physical.

On their way from Pawiak and Warsaw to Vittell, France, in preparation for an exchange that will ensure their passage to the United States, Berg writes about the beauty of the countryside in Germany, specifically along the Rhine. She writes, “Yesterday we travelled across Germany all day long. We took a detour to avoid passing through Berlin. The most beautiful part of our trip was along the winding river Rhine, with its verdant hills and rich vineyards.” Even though she and her family are not free at this point, she still sees beauty in the world and the landscape, describing the view along the as “the most beautiful part of our trip.” Yet, even amongst this beauty the horrors of war remain. In the afternoon, they “reached Saarbruecken, where, for the first time, [they] saw traces of ruin, caused, probably, by Allied bombs.”

Berg and her family are far way from the Ghetto during the uprising in 1943. She hears about the events second hand when she receives letters from others and encounters individuals who survived the uprising. In this moment, Berg feels guilt at her and her family’s seeming safety away from the threat of death in the Ghetto or deportation to Treblinka or elsewhere. She asks herself, “Had we the right to save ourselves?” She thinks about the beauty she enjoys in Vittell, the park she walks around and the landscape she sees everyday. She asks, “Why is it so beautiful in this part of the world? Here, everything smells of sun and flowers, and there — there is only blood, the blood of my own people.” Berg knows that even amongst the beauty death stalks and remains. She continues, “Here I am, breathing fresh air, and there my people are suffocating in gas and perishing in flames, burned alive. Why?”

Berg feels survivor’s guilt, but she does not wallow in it,. Instead, she uses her guilt to tell the world what has happened and what continues to happen. Her diary ends in March 1943 upon her arrival to the United States. At the end, she writes, “I will tell, I will tell everything, about our sufferings and our struggles and the slaughter of our dearest, and I will demand punishment for the German murderers and their Gretchens in Berlin, Munich, and Nuremberg who enjoyed the fruits of murder.” Her and her family did just that. A month after their arrival, they marched from the Warsaw Synagogue in New York to city hall, carrying signs that read, “We appeal to the conscience of America to help save the Jews of Poland who can yet be saved,” and “Three Million Polish Jews have been murdered by the Nazis! Help us resuce the survivors.”

Susan Pentlin points out that Berg’s’ diary appeared before the end of the war, serving as one of the first hand accounts of the Nazi regieme’s Final Solution. It appeared, as Pentlin notes, “before people in the United States and abroad, and even the diarist herself, knew the enormity of the German crimes and the detials of the Final Solution.” Berg’s diary was the first publication in English to describe the establishment of the ghetto and of the deportations. Berg details the violence, the murder, the gory details of Nazi rule, but even amongst all of this, she describes the beauty of the world as a form of resistance. Traveling across the Atlantic, Berg writes, “I went out on deck and breathed in the endless blueness. The blood-drenched earth of Europe was behind me. The feeling of freedom almost took my breath away.”

The Diary of Mary Berg is an important reminder of history and the ways that community and beauty serve as resistance to violence and oppression. I could write more on this, but I will leave it here for now. What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.bsky.social.