A few weeks ago, someone told me about the work of neurologist and psychologist Viktor Frankl and his time in a concentration camp duroing World War II. After the person told me about Frankl, I sought out his memoir Man’s Search for Meaning where he lays out his ideas surrounding logotherapy. Frankl explains that logotherapy, which derives from logos, the Greek word for “meaning,” “focuses on the meaning of human existence as well as on man’s search for such a meaning.” He details, when relating his time in the Nazi concentration camps, the ways that one’s meaning of their existence kept them from descending into apathy and succumbing to death behind the barbed wire fences and guard towers. Part of this meaning, too, arose from the creation of art and the sight of beauty.

Frankl notes that many may find it difficult to believe that art permeated the concentration camps, just as we may say the same when we read Mary Berg’s diary about living in the Warsaw Ghetto. Yet, art and beauty sustained individuals. When individuals started thinking about their lives, they “also experienced the beauty of art and nature as never before.” These thoughts caused the individual to “sometimes even forget his own frightful circumstances.” To drive this point home, Frankl points out that if one were to look into the box cars of individuals as they moved “from Auschwitz to a Bavarian camp” as they looked out of the box car and “beheld the mountains of Salzburg with their summits glowing in the sunset,” then one would see the hope and determination in their visages, not a sight of those “who had given up all hope of life and liberty.”

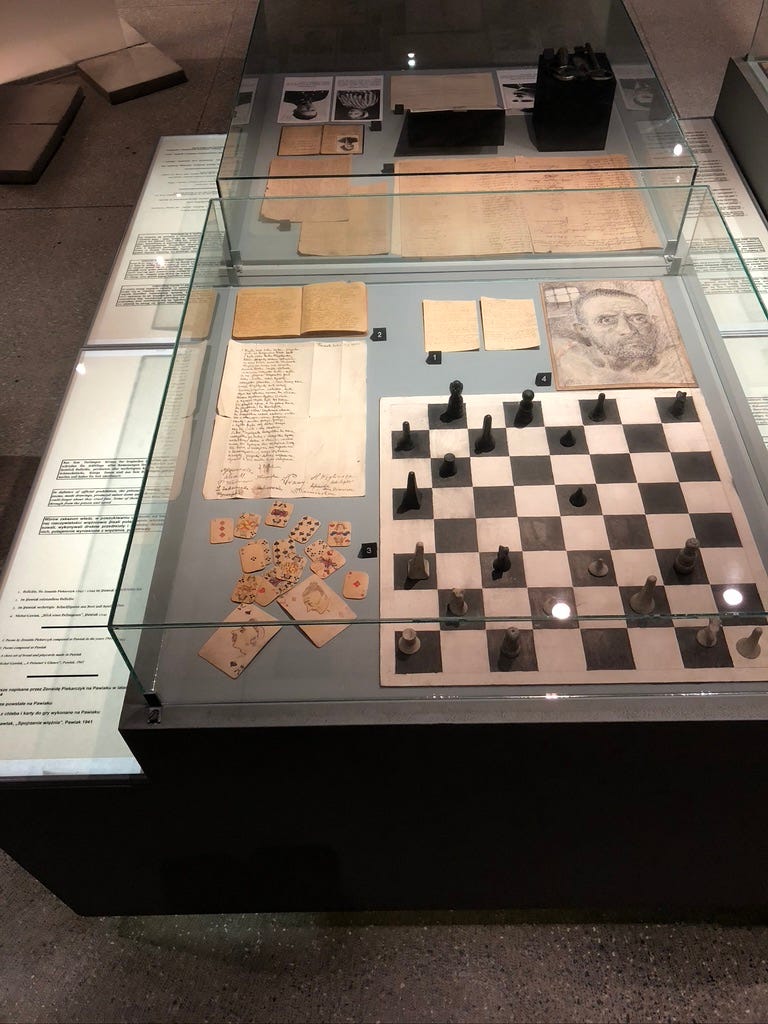

Frankl details the ways that those within the camps created cabarets and plays; wrote poetry and prose; painted and sculpted. I’ve seen this myself, especially when I went to Camps des Milles in France. Art serves as a means of escape from a violent and oppressive situation, and it also, more importantly, serves as an act of resistance. On visiting Camps des Milles, I wrote,

[A]s I toured Camps des Milles, an interment camp near Aix en Provence, I was reminded of the role and power of art as resistance. The Germans interned countless artists and intellectuals such as Lion Feuchtwanger, Max Ernst, Otto Fritz Meyerhof, and more at Camps des Milles, and the tour highlighted the role of art within the camp as a mode of resistance. Art covers the walls next to the kilns where the internees slept. Polish artist Julius Mohr painted flowers on the walls, and other internees drew various things on the walls such as a heart inscribed with “La liberte, La vie, La paix.”

Art, however one defines it, sustains. It reflects the world back to us. It tells us, as James Baldwin so powerfully reminds us, that we may think we are alone the world and that our pain is unique, but then we encounter books and art. At that moment, Baldwin writes, we realize “that the things that tormented [us] most were the very things that connected [us] with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.” We link together, realizing the universal nature of our struggles, across class, ethnic, gendered, regional, barriers. Art stems from a place of pain and suffering, it exists, at a tension within ourselves and within our society.

I view art, in many ways, as prophetic. That is not to say that all artists are prophets, but I am a believer in the fact that artists see things happening before most people and they create as a way to both warn and explain. They create as a way to change. The Old Testament prophets worked in a similar manner, telling the people what they had done against God and warning them about what would happen if they continued down the same path. Prophets don’t get accolades from the majority of the public. They don’t get parades. They don’t get rewarded. Yet, they warn us, they bring us along. As George Butendorp put it, “An artist is like a prophet. He must lead people and help them get acquainted with what he sees.” Artists present and lead, and we must choose to follow.

Fascism seeks to destroy art. Think about the artistic explosion in Berlin and Germany during the Weimar era and then statements such as those by Alfred Rosenberg, from the Kampfbund für deutsche Kultur, who called “for resistance to all tendencies in the theater which are damaging to the people, for the theater in nearly all big cities has become the scene of perverted instincts. We fight against a constantly spreading corruption of our concepts of justice, a corruption which gives the big swindlers practically a free hand in exploiting the people.” When I read things like this, or even things such as Adolf Hitler in Mein Kampf arguing that all advancements in culture, science, and technology are “the creative product of only a small number of nations” and people, I think to the United Daughters of the Confederacy working hard to eliminate anything that deemed “unjust to the South” from the public space. Any art that resists or that goes against their position must be removed and exhumed from the public lest individuals consume it and see the dangers right in front of them.

I cannot help, when I read these words and think about art, but also turn my attention to Stephen Miller’s speech at Charlie Kirk’s funeral . There, he attacked “our enemies” and claimed a Western lineage to Athens and Rome and Philadelphia and Monticello. He continued by addressing the perceived “enemy” and telling us, “You are nothing. You have nothing. You are wickedness, you are jealousy, you are envy, you are hatred. You are nothing! You can build nothing, you can produce nothing. You can create nothing.” When thinking about art and culture, this latter part stood out, and Miller basically proclaimed that those who oppose the ideologies and positions of the administration and himself cannot create anything. I think about this comment and am reminded of Frankl of Berg of Solomon Northup of Harriet Jacobs of Toni Morrison of Anna Seghers of . . .

Resistance and defiance brought us Pablo Picasso’s Guernica. Resistance and defiance brought us Anna Seghers’ The Seventh Cross. Resistance and defiance brought us Ernest Gaines’ Of Love and Dust. Resistance and defiance brought us Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly. Resistance and defiance brought us Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Resistance and defiance brought us Woody Guthrie’s oeuvre. Resistance and defiance brought us the pieces of art, the sculptures, and the other items that victims of the Nazi regime created. No matter the work of influential art, resistance and defiance probably helped to create it.

Art, as Frankl explained, sustains, but it also resists. It arises in a grotesque manner, as Frankl puts it when talking about art in the camps, coming “from the ghostlike contrast between the performance and the background of desolate camp life.” It says, “This is the reality. This is my resistance to that reality and the inhumane treatment.” It tells us about ourselves while at the same time pushing us, leading us, to thinking about a better world for all. What are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.