Over the past few days, I’ve had to pull together a literature and composition course for the fall semester. As I thought about the course, I moved from Appalachian literature with writers such as Crystal Wilkinson, David Joy, and S.A. Cosby to mystery novels with Cosby and others to my already planned “The Reverberations of World War II” syllabus for a more introductory course. However, the more I thought about it, I decided to do a course on superheroes, hopefully making the reader a little more enjoyable for students and providing them with ways to critically engage with literature and popular culture.

When I first started thinking about this framing, I thought about doing Don McGregor’s then parts of Christopher Priest’s Black Panther runs, some Luke Cage, some Captain America, and other series from the big two. The more I thought about this, the course became more unwieldy because with so much to pull from I didn’t know where to focus. This led me to look at my shelf and see John Ridley and George Jeanty’s The American Dream, a series that critiques superheroes themselves as well as critiquing society and politics. With that, I decided to focus the course on similar series, stretching back to Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen and into the present with Chip Zdarsky and Daniel Acuna’s Avengers: Twilight.

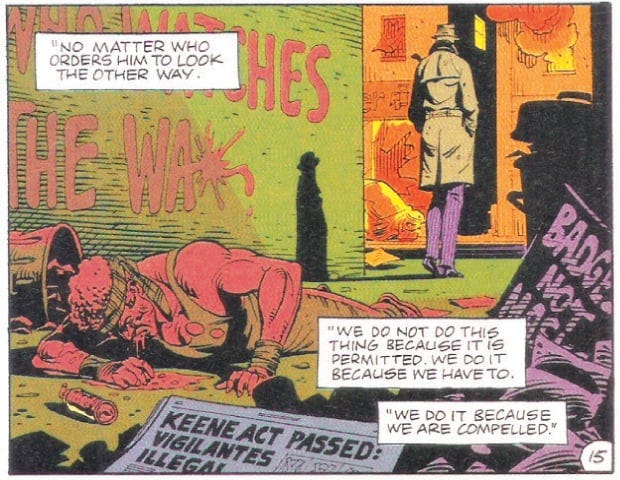

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?

Overview:

Superheroes are as American as apple pie and baseball. Superman, Batman, Captain America, and others all arose out of mid-twentieth century America as creators such as Jerry Siegel and Joel Schuster (Superman), Bob Kane and Bill Finger (Batman), and Jack Kirby and Joe Simon (Captain America) dealt with issues of modernity, xenophobia, classism, fascism, and more. Over the years, superheroes have spread across our zeitgeist, both nationally and globally, spanning billion dollar enterprises in films and streaming series. Everyday we encounter images of superheroes on clothing, in advertisements, on our screens, on bumper stickers, and elsewhere.

The role of the superhero is to, as Peter Coogan puts it, to be “pro-social and selfless, which means that his fight against evil must fit with the existing, professed mores of society and must not be intended to benefit or further his own agenda.” Key within Coogan’s definition of the superhero’s mission is that the superhero fights to uphold the “professed mores of society,” but what happens when those “professed mores” oppress and subjugate individuals? Comics have always questioned structural power, from Monica Lynne (T’Challa’s girlfriend in the early 1970s The Avengers) calling the Avengers tools of the state or even T’Challa himself saying he joined The Avengers to spy on them or Superman championing the oppressed against corporate greed in some of his early stories.

However, the 1980s saw a shift in comics from the lauding of superheroes to the questioning of their roles and motives within the fictional universes they inhabiting, a questioning that extended into the world that we inhabit since literature is merely an extension of the communities we inhabit. Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen asked us to think about who watches the superheroes and keeps them in check, making sure their actions serve society and not just the government or special interests. Likewise, Frank Miller and Klaus Janson’s The Dark Knight Returns uses Batman to critique. as Aldo Regaldo puts it, “a capitalistic society that places a premium on profit, competition, and entertainment over the values of compassion, humanity, and community.” Each, as well, serve as critiques of Regan era foreign and domestic policy, pushing back against the myth of American prosperity at home and the role of the United States abroad.

Comics, like any other art form, have always served as a source of social and political commentary, and in this course, we will explore how these series comment on the social and political moments in which they arose from the mid-1980s to the present. As well, we will examine the origins of superheroes, looking at texts that both seek to define superheroes and their historical position in American society, and how series such as Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and others critique the prevailing ideas of superheroes and their roles in society. Finally, we will see where, as Geoff Klock points out, comics moved from “fantasy” to “literature” as they began to become self-reflective, examining the superhero genre itself.

Primary Texts:

Millar, Mark and Dave Johnson. Superman: Red Son.

Miller, Frank and Klaus Janson. The Dark Knight Returns.

Moore, Alan and Dave Gibbons. Watchmen.

Ridley, John and Georges Jeanty. The American Way.

Ridley, John and Georges Jeanty. The American Way: Those Above and Those Below.

Zdarsky, Chip and Daniel Acuna. Avengers: Twilight.

Secondary Readings (I will provide these):

Bukatman, Scott. “A Song of the Urban Superhero.”

Coogan, Peter. “The Definition of a Superhero.”

Klock, Geoff. “The Revisionary Superhero Narrative.”

Regaldo, Aldo. “From Steel and Shadows to the Flag.”

Regaldo, Aldo. “From Renaissance to the Dark Age.”

Course Requirements:

Assignments — Throughout the semester, we will have both in-class and online assignments. These will include posting topics online, answering questions, or other such activities. There will be small group discussions during classes and other activities that will be part of this grade

Conferences — We will have conferences for each paper. These will be mandatory because they allow us to discuss your essays in a smaller setting, giving us more time to work through your questions.

Essays — The essays will each be between 750–1000 words. They will highlight your engagement with the course material through your use of argument, sources, and critical thinking. For each, you must have a succinct argument and support the argument with examples from both primary and secondary texts.

Unessay and Unessay Paper — The Unessay is meant to get you to think about literature in more than just a textual manner. It is meant to help free you from the constraints of the traditional essay and to allow you to be creative with your research. The Unessay will consist of two parts: a finished product and a 1,500–2,000 word essay describing how your research influenced your finished product. You will present your finished product to the rest of the class at the end of the semester. You will turn in your unessay paper before finals. The paper will discuss the material and research you used to create your final product.