Whenever I have a course that focuses on comics or graphic narratives, I usually have students create their own graphic text. For this assignment, students have the choice of either doing a script or an actual, completed graphic text. They can work solo or together, use photos, and essentially approach the assignment in any way they want to approach it. This semester, I assigned this project to students in my World Literature and Graphic Novel course. The assignment varies depending on what course I use it in, and for this course, since it is focused on world literature and we are looking at historical events, students must create either a graphic text or script based on an historical event that they want to know more about. Along with this part, they must also write a reflective essay where they discuss their research and choices in the creation of the script or graphic text.

The first time I gave this assignment, I created a graphic text on Lillian Smith. This semester, I wanted to create another graphic text, but I wanted to create something different. In another course, I had students create zines, and I created a few minizines to share as examples. As well, I started working on a larger twenty-four page zine, but the more I got into that project, I felt like it was turning more into a graphic text akin to the Lillian Smith text. So, I changed direction and created a sixteen-page graphic text on the 1868 Bossier Massacre and its reverberations that still resonate today.

From the outset, I knew I wanted to do either a zine or a graphic text on the Bossier Massacre, an event where over 160 Black men, women, and children were killed in a white supremacist act of voter suppression and an event that took place in my hometown. Due to the time constraints, I recognized that I could not present all of the information that I wanted to present, but I knew that I could create something that conveyed information about the massacre. Initially, I thought about doing something akin to Nora Krug’s Belonging, looking at my family history in the area and thinking about the impact of these events on them. Ultimately, I decided to leave this thread behind; however, I did choose on working in a similar style to Krug, namely through collage and the use of primary texts within the project.

The finished project doesn’t have a narrative element. It doesn’t follow a singular character or a group of characters. While I do intersperse myself into the text at one point, I rely, mostly, on primary texts and scholarly sources. I did this because instead of providing commentary through my own words I wanted readers to engage with the primary texts from the contemporaneous moment in 1868 and the words of historians looking back at 1868. Along with these words, I chose specific images to accompany them, both historical and from the present moment, providing the juxtaposition between text and image.

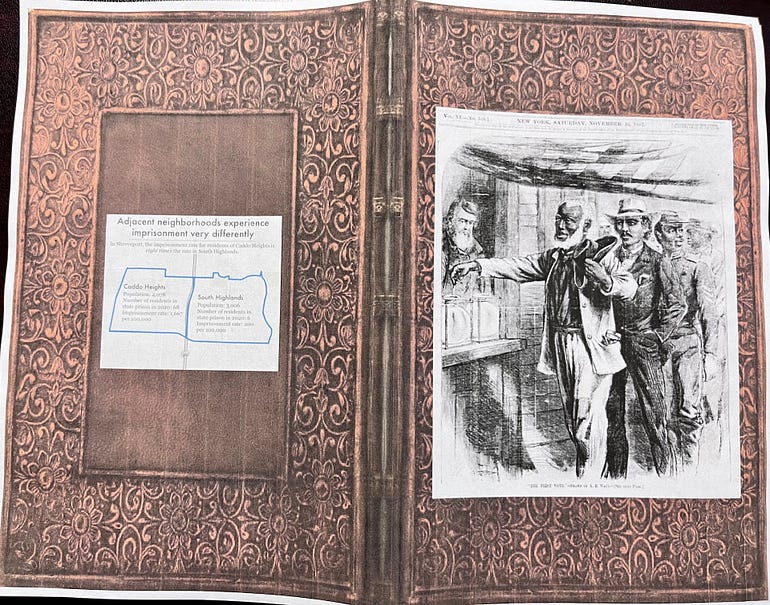

I wanted to make it feel like a book, so I found clipart images for a book cover, faded composition pages, and other similar backgrounds. I wanted to created a textured feel, even if the printout or computer screen could not convey that texture when someone touched it. Along with this feel, I also learned how to edit images and text in PowerPoint, removing backgrounds, using transparency features, merging images, and other tools that created a unique aesthetic for the completed product.

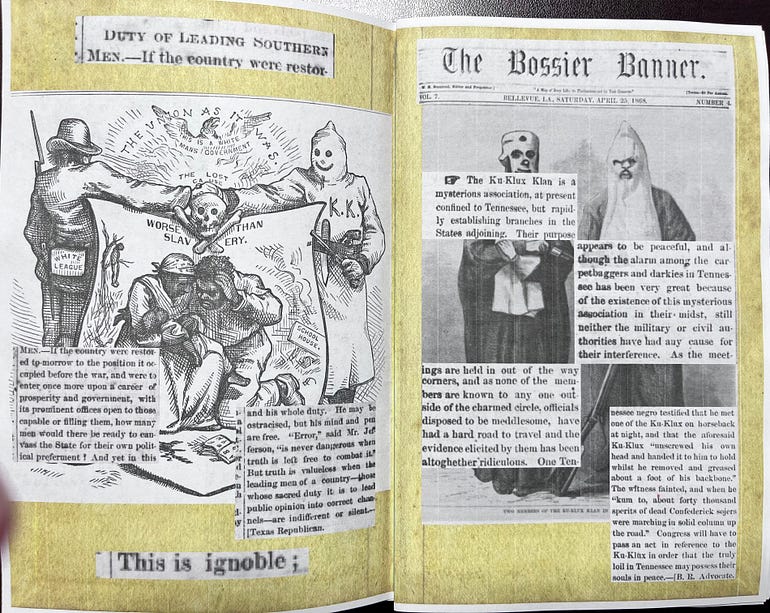

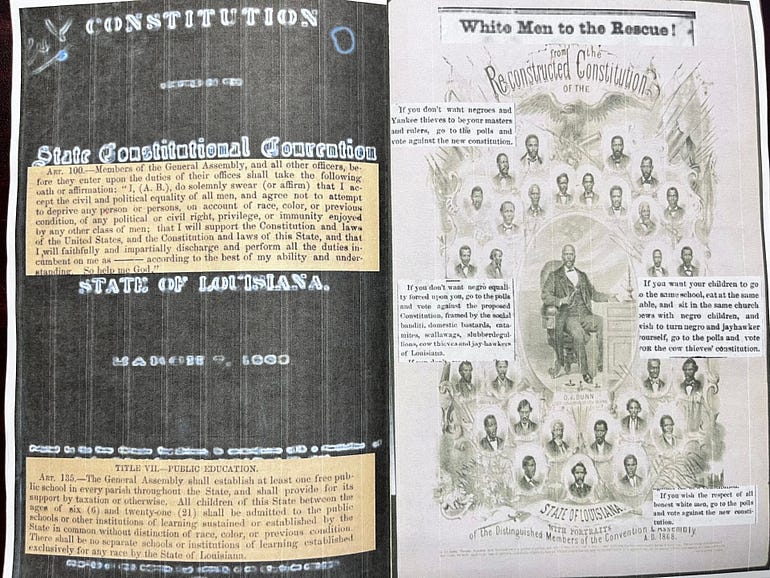

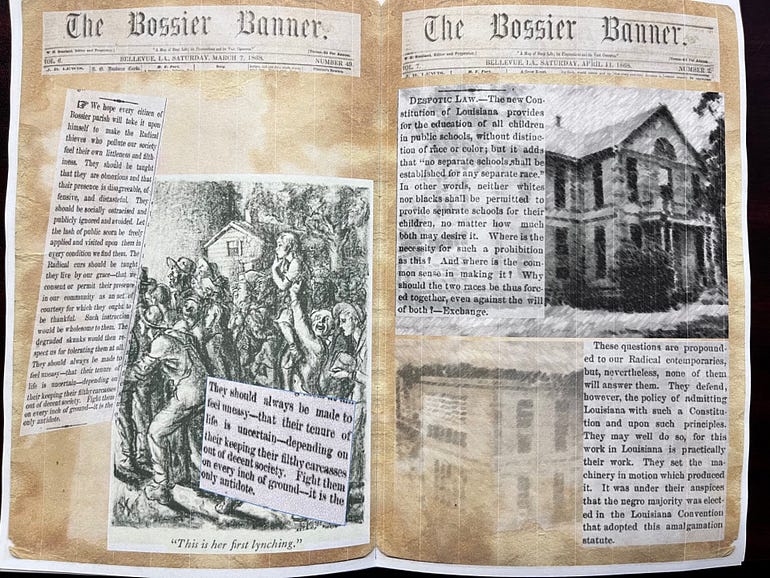

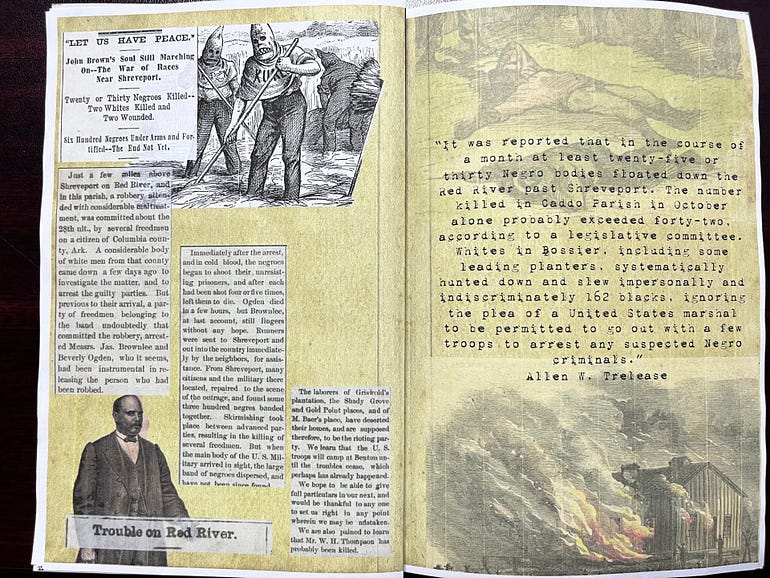

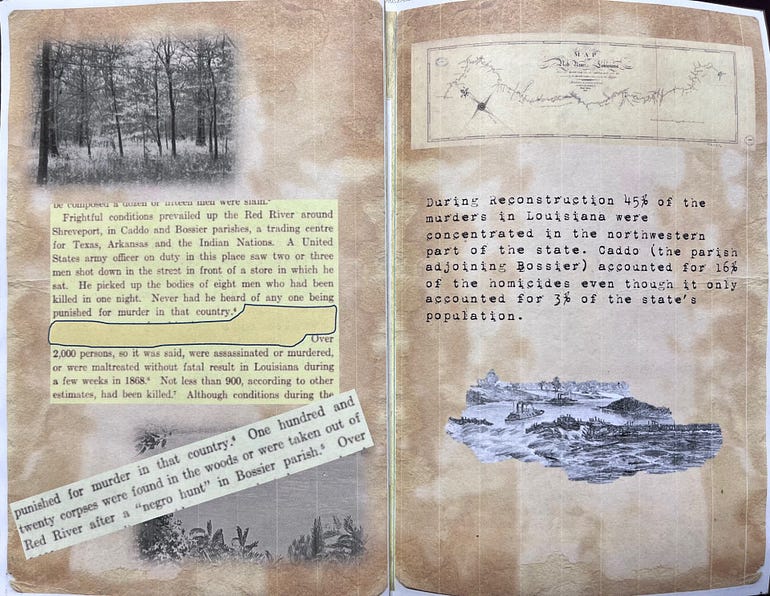

For the content, I pulled multiple articles from the Bossier Banner, specifically ones related to the white supremacist resistance to the 1868 Louisiana Constitution in the spring, the Ku Klux Klan, and a later article from an unknown newspaper at this point, relating the events of the Bossier Massacre in the fall of 1868. Along with these articles, I included quotes from the 1868 Louisiana Constitution, notably in regard to education because the public education part of the constitution is what the Bossier Banner articles rile against since the constitution called for education for all, regardless or race, and for integration. For this section, I did a two-page spread, with the left page being excerpts from the constitution and the right page, with an image of the constitutional convention as the background, an article entitled “White Men to the Rescue!” which argued against voting for the constitution because it promoted equality and integration.

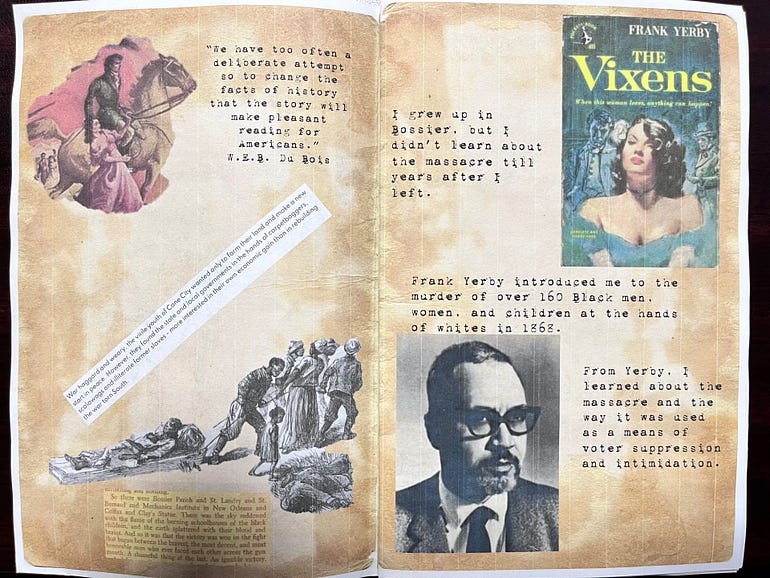

The articles make up the bulk of the text, but I begin the text with a quote from W.E.B. Du Bois’ essay “The Propaganda of History” where he writes, “We have too often a deliberate attempt so to change the facts of history that the story will make pleasant reading for Americans.” This quote appears to the right of a cropped image of the cover of Frank Yerby’s The Vixens, the novel where I learned about the Bossier Massacre. Directly below, in the middle of the page, I present an excerpt from Louise Stinson’s speech in 1976 where she promotes the Lost Cause narrative of the South, thus positining Stinson in direct relation to Du Bois’ quote. The bottom of the page contains a cropped image from Harper’s Weekly of the Colfax Massacre along with a paragraph from The Vixens that lists the massacres in Louisiana during Reconstruction, again providing a counter to Stinson’s Lost Cause narrative. Accompanying this page, I have one with another cover of The Vixens and an image of Yerby along with a description of how I learned about the massacre from Yerby’s novel.

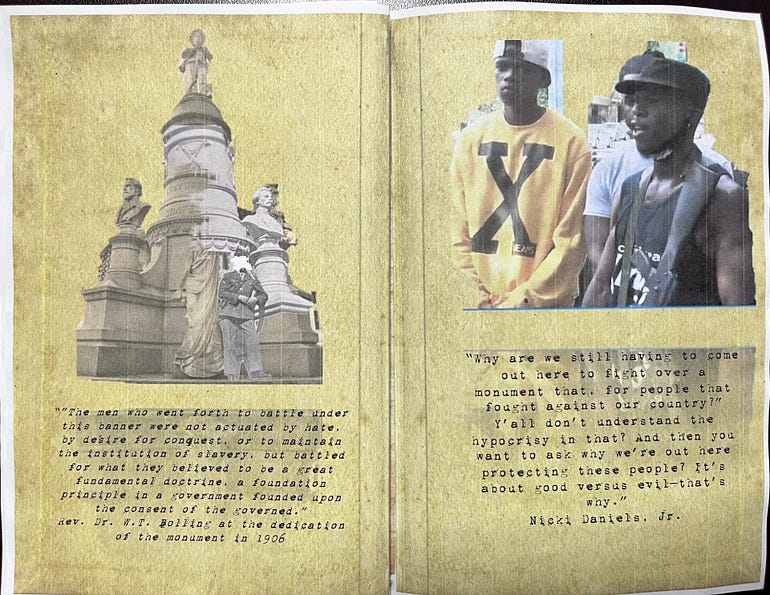

At the end of the product, I zoom outwards to the current moment, specifically the discussion surrounding the Confederate monument that the United Daughters of the Confederacy erected in Caddo Parish, the parish next to Bossier, in 1906. I have a quote from Rev. Dr. W. T. Bolling from the dedication, a quote that reads just like Stinson in 1976 and that exudes Lost Cause rhetoric. Adjoining this page, I have an image of Nicki Daniels, Jr. and another Black man who, in 2020, went to the monument to help protect protestors. They openly carried weapons, which is legal in Louisiana, and Daniels pointed out that having to fight over a monument to an institution that subjected individuals like him to enslavement is part and parcel of the nation’s and the region’s history. Adding to this, I conclude the product with a map from Prison Policy that points out the disparities in incarceration rates in two adjoining neighborhoods in Shreveport, a part of Caddo Parish. I ended with this image to highlight the continued legacy of white supremacy in the region and the ways it still appears.

Most of the information I used in the text comes from a piece about the Bossier Massacre I wrote a couple of years ago. Visit Nobody’s Home to read more. Below, you can see the finished product. What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.