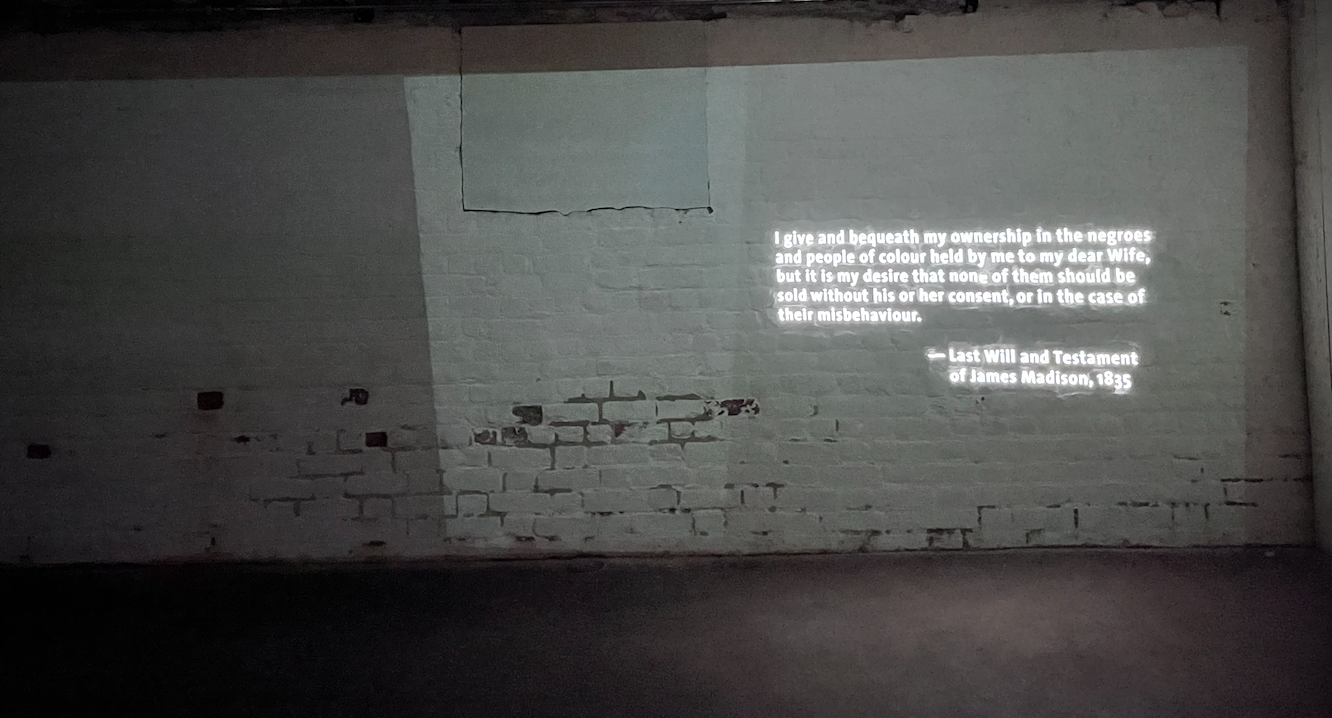

Of the first 18 Presidents of the United States, 12, at some point in their lives, enslaved individuals, and 8 enslaved individuals during their presidency. James Madison, the 4th President of the United States and the Father of the Constitution, was one of the latter, enslaving over 100 individuals before, during, and after his time in office. In his will, in 1835, Madison wrote, “I give and bequeath my ownership in the negroes and people of colour held by me to my dear Wife, but it is my desire that none of them should be sold without his or her consent, or in the case of misbehavior.” Madison did not free any of the individuals he enslaved, and upon his death, his wife Dolley did not adhere to his wishes, selling individuals and separating families without their consent.

While James Madison did not write the Constitution of the United States on his own, he is considered the Father of the Constitution, and he would sit in his library at Montpelier, looking out at his plantation and the Blue Ridge Mountain and think about the formation of the new nation. His desk faced the front of his house and the mountains which gave him inspiration and solace. However, if he lowered his gaze some, just beyond the hedges and looked at those who toiled in the tobacco fields, those he enslaved, he would have see that all of the grandiose verbage he and the nation did not live up to the enlightenment ideals laid out in the nation’s founding document.

In the Declaration of Independence in 1776, Thomas Jefferson, who also enslaved individuals, proclaimed, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Eleven years later, in 1787, the Constitutional Convention met and drafted what would become the Constitution of the United States. The preamble reads, “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

In each of these documents, we must ask, “Who are ‘all men’?” and “Who are ‘the people’?” These do not include, “all.” It did not include “all men” or “all people.” We need only think about Abigail Adams’ plead to her husband John Adams in March 1776, “I desire you would Remember the Ladies, and be more generous and favourable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands. Remember all Men would be tyrants if they could. If perticuliar care and attention is not paid to the Laidies we are determined to foment a Rebelion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.” John scoffed at Abigail’s request, telling her that the me “know better than to repeal our Masculine systems” and that women have joined the voices of other groups (Black, Indigenous, and more) in expressing their desire for equal privileges under the law.

During the Constitutional Convention, delegates reached an impasse at one point over representation in congress which ultimately boiled down to the protection of slavery by southern states. The constitution doesn’t mention “slavery” at any point in the text; however, slavery hovers the document with the Three-Fifths Compromise. Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, in Tyranny of the Minority, point out that the Southern states would do everything they could to protect slavery. They write, “But the Southern slaverholders were a minority, both in the convention and in America. Overall, the population of the eight northern states roughly matched that of the five southern states. However, since 40 percent of the southern population were enslaved peo[le who had no voting rights and because southern states had more restrictive voting laws, the North had a much larger voting population and would likely prevail in any national election.” Madison saw that the fledgling union could dissolve over the issue of slavery.

As a result of all of this, the constitution contains the Three-Fifths Compromise, which appears in Article 1, Section 2 of the document, the section that details the election of representatives to Congress. The text reads, “Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.” This meant that enslaved individuals would count for three-fifths of a person, thus increasing the southern states’ representation in Congress.

Levistky and Ziblatt provide an example from 1790. That year, “Massachusetts’ voting population was greater than Virginia’s, but since Virginia had 300,000 slaves, it was given five more representatives to Congress than Massachusetts.” New Hampshire and South Carolina had the same number of free citizens as well; but since South Carolina enslaved 100,000 people, they had two more representatives in Congree than New Hampshire. “Overall,” Levitsky and Ziblatt continue, “the three-fifths clause increased the South’s representation in the House of Representatives by 25 percent,” giving them around half of the control of the chamber. This led to stymied legislation and compromises through the Civil War and beyond.

Following the convention, the states needed to rarify the constitution, and to promote ratification, Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay wrote the Federalist Papers to argue for its adoption. In Federalist 54, Madison addresses the Three-Fifths Compromise. Madison makes the argument for the clause, but he also, through the paper, points out the morally illogical argument of the compromise itself. He begins by pointing out that those who object to the clause note that “[s]laves are considered as property, not as persons” and should be considered in taxation by not representation. However, he then ties himself into a not to support the clause when he writes, “But we must deny the fact, that slaves are considered merely as property, and in no respect whatever as persons. The true state of the case is, that they partake of both these qualities: being considered by our laws, in some respects, as persons, and in other respects as property.”

Madison argues that enslaved individuals are both “persons” and “property,” thus granting them humanity while also continuing to dehumanize them and enslave them. Madison contends that enslaved individuals do not work for themselves “but for a master,” and that the enslaver holds ownership over them; thus, “the slave may appear to be degraded from the human rank, and classed with those irrational animals which fall under the legal denomination of property.” Yet, Madison continues that the laws, in protecting enslaved individuals “against the violence of all others, the slave is no less evidently regarded by the law as a member of the society, not as part of the irrational creation; as a moral person, not as a mere object of property.”

The compromise, in Madison’s argument, treats enslaved individuals about both people and property, but Madison also argues that the law enslaves individuals, making them “property,” and “that if the laws were to restore the rights which have been taken away, the negroes could no longer be refused an equal share of representation with the other inhabitants.” Madison, like Jefferson and other founders, had contradictory thoughts on liberty and representation when faced with enslavement. His argument, of the law stripping enslaved individuals of two-fifths of their humanity, since they were property, debases them while also using the other three-fifths to uphold the institution of slavery to support himself and others.

As I stood in Madison’s library, looking at the bookshelves containing texts he read and at the desk where he sat, gazing out on the land, I thought about all of this. I thought about the fact that Madison and Dolley never had any children, but, as I learned visiting the property and the exhibit about the enslaved at Montpellier, he probably fathered a child when he raped his enslaved cook Coreen. I think about Paul Jennings, born in 1799 and enslaved by Madison, who, at the age of 10, accompanied the Madison’s to the White House, and who, at the age of 15, during the war of 1812, saved a portrait of George Washington from the White House. Daniel Webster bought Jennings freedom in 1846, and he worked as an abolitionist. I thought about Coreen and Jennings. I thought about the enslaved children whose fingerprints can be seen in the bricks at Montpelier. I thought about all of these individuals, and more, in the shadow of Madison who championed “the people,” freedom, equality, and liberty.

Now, nearly 250 years after the Declaration of Independence, we face the same questions I asked earlier: “Who are ‘all men’?” and “Who are ‘the people’?” How we answer those questions will determine our next 250 years and if this democratic experiment will continue or cease to exist. What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.bsky.social.