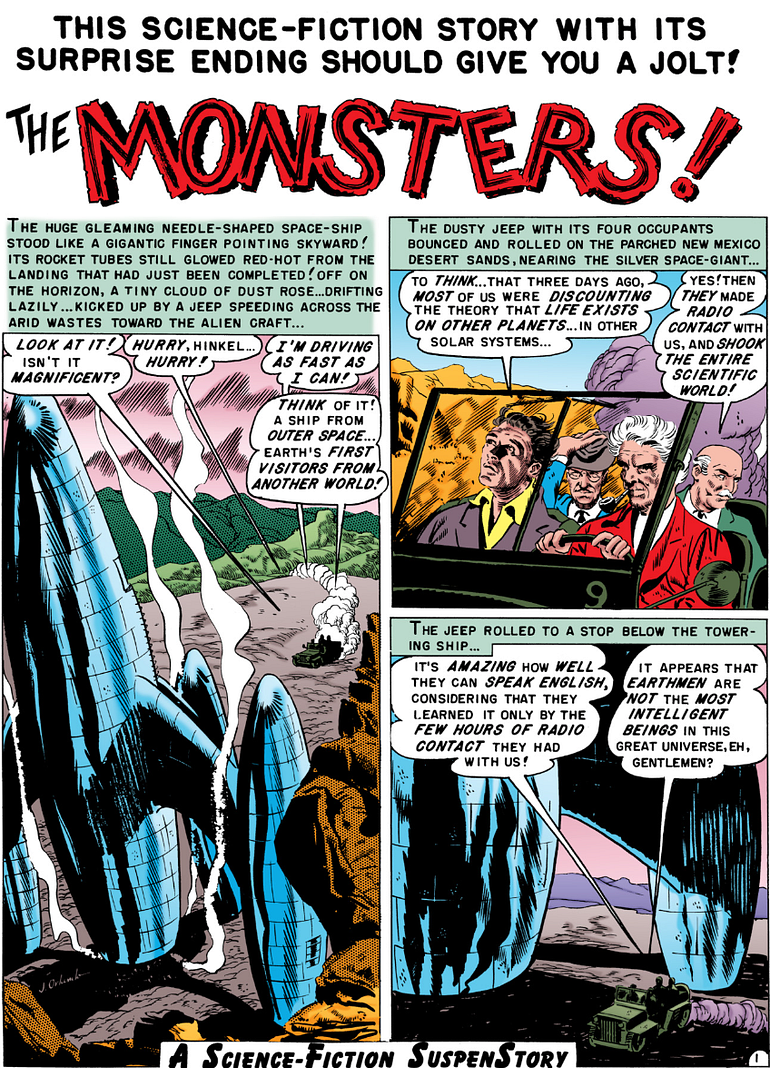

Over the past few weeks, I’ve written about a few of the stories from EC Comic’s Weird Fantasy series in relation to race. I noted how “The Green Thing” addresses the racist trope of contagion and of tainted blood, and I discussed how “Counter-Clockwise” uses positioing to place the white reader in the position of those that they discriminate against. Today, I want to continue this thread by looking at another science fiction story in Shock SuspenStories #1, a series that EC started to showcase the various types of comics they produced. Each issue contained a horror story, a war story, a crime story, and a science fiction story. “The Monsters!” appeared in the first issue from February and March 1952, almost exactly one year before the monumental story “Judgement Day!” in Weird Fantasy #18.

Like the other stories I have examined, Joe Orlando, Bill Gaines, and Al Feldstein’s “The Monsters!” uses science fiction to examine racism and white supremacy, as only EC Comics does. The story turns a lens on the white reader, much like “Counter-Clockwise,” calling upon them to look at them selves in the mirror and face their own reflections. “The Monsters!” accomplishes this through, as usual, the use of extraterrestrials that point out the racist thoughts and hypocrisies that the white readers hold so dear. This assertion may seem absurd at first glance, but when you really dig into what happens over the six-page story, the undercurrent comes to the surface.

The story focuses on a group of four men who serve as representatives of the United States on their way to meet a spaceship that has landed in the desert. When they approach the ship, they comment on how the extraterrestrials are “much more advanced scientifically” how much they can learn from the visitors. However, the extraterrestrials tells the men that they have changed their minds and will not meet with them, but before they leave, they tell the men that they explain, through a story, their “reasons for leaving” without engaging further. One of the men comments that they want to hear the story and that the reasons “can’t be too strong” for why the visitors choose to leave. The men feel full of themselves, as if they don’t have anything wrong with them.

The visitors commence to ask the men to imagine an accident at an atomic laboratory where the workers become infected with radiation. When the workers get their partners pregnant and have children, each of the children, as one father screams, are “hideous.” We never see the babies; instead, we merely see two from from inside the nursery at the hospital, and one with a nurse holding a bundle, in which the baby is wrapped. Following the births, the visitors tell the men that the government took the “three mutants” to study them, and we see a doctor talking with his assistant about the children and asking her to transcribe what he says.

Over the course of three panels, the doctor describes the “mutants,” and the assistant envisions them in her own head. In the first panel, the doctor says they have “an oversized bulbous head” and that “[b]etween the visual organs” they have what appears to be “a large pointed olfactory organ.” He continues by stating thy gave “two large vents fringed with fine cilia” and “a tremendous cavity lined with a mucous membrane.” As she listens, the assistant pictures a monstrous face with large ears, a large pointed nose, hair everywhere, and a protruding tongue. Next, the doctor states that they have “bony appendages of varied shapes” that they have a “coarse and thick hide” that occasionally “becomes drenched with foul-smelling acids which ooze from porous openings,” and “other liquids” that emanate from other cavities. Here, the assistant pictures a monstrously contorted baby trying to hold a bottle and a book.

Finally, the doctor says that the mutants are “short and cylindrical” and that they have “four triple-sectioned appendage[s]” with several more appendages off of each of these, concluding in “a horny scale resembling a talon.” Again, the assistant envisions a deformed being, and we see her, as she listens, with sweat pouring down her forehead. The images she crafts in her mind, based on the doctor’s descriptions, scare her, and he she tells him that doesn’t feel so good. She experiences revulsion and fear at what she hears, and that makes her sick.

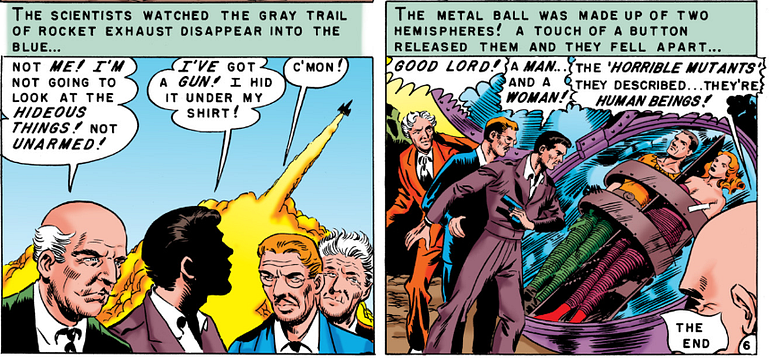

The news media picks up where the doctor left off, telling the populace that the “[m]utants are carnivorous . . . feeding on other forms of animal life for sustenance!” In this panel, we see the newscaster make the statement while three men eat a meal at a cafeteria. People say the mutants lack intelligence, are “selfish. . . ruthless . . . sadistic . . . and egotistical” and that all they want to do is reproduce, with all other desires becoming “subservient to this.” Finally, we see two doctors in a lab, preparing to conduct an experiment on a rabbit. One doctor, as he fills a syringe, says, “Mutants appear to despise and maltreat life-forms inferior to their own! It is possible that they would, if they could, kill us!” His partner replies, “They should be destroyed! Before there are too many of them!”

At this, the visitors conclude their story. The men don’t understand it, but the visitors refuse to explain. They do tell the men, as their space ship prepares to rocket into the air, that the “mutants” they described “actually were born. To see them, the visitors tell the men to look in the capsule that they leave behind because it contains “two of them.” When the men walk over the capsule, they open it and stand aghast because inside they se a man and a woman. The story ends as the men gaze upon the “mutants” and one of them proclaims, “The ‘horrible mutants’ they described . . . they’re human beings!” Notably, he says “they’re human beings,” not “they’re us.” By saying the former, he removes himself, at this point, from the individuals in the capsule, not inclduing them in his own definition of himself. This refusal plays into reading “The Monsters!” through the lens of race.

If we look back at the story, we discover that the doctor’s description of the “mutants” simply describes humans. He describes our faces, our eyes, our noses, our bodies, our arms, our legs, our hands, our feet, our nails. He describes how we sweat from our skin. The following panels describe how we eat meat, our negative emotions, how we treat one another, and more. We can read these aspects in two ways. On one hand, we can read them in racial terms, as if the “mutants” are non-whites and the reveal at the end highlights our shared huamnity, even though the man and woman in the capsule are white. I say this because like “The Green Thing,” this story appears before “Judgment Day!” If we read it in light of “Judgment Day!,” it carries a similar plot, only without the reveal of the visitors being Black.

Another way to read the ending is in relation to the ways we encounter and view ourselves. We are afraid to view ourselves as “mutants” as “bad” as “causing harm.” We view ourselves as “good” and “noble.” If we think about this, again, through the lens of race, we can view it in relation to the way the oppressor views themselves. It’s the mirror. When we look at our reflections and confront our hideous views, we have two choices. One, we can take that information and work on changing our views, learning from our mistakes. Two, we can double down on our hideous perspectives and ignore what we see, blaming others, instead of ourselves.

As I read “The Monsters!,” I couldn’t help but think about this. I had just read Kwame Ture’s (Stokely Carmichael) “Black Power” speech from October 1966 where he makes the point that we, as individuals, cannot condemn ourselves. If we condemn ourselves, then we must acknowledge our hideous views that harm others, and in that condemnation, we must destroy parts of ourselves or our whole selves. This leads people to fear because they do not want to harm themselves because in so doing they will shatter their very identity and very being. Rather, they will plant their feet in the ground and stand firm in their views because in that manner they will “protect” themselves. Yet, this “protection” harms others because it continues the oppression.

I think about Lillian Smith and the camp she ran. At the camp, they talked about white supremacy, gender, religion, sex, and life. People knew that Smith opposed segregation, and she said that segregationist politicians sent their daughters to the camp because they didn’t want their kids to be like them. This highlights the point. The politicians, in this acknowledgement, knew what they stood for in public was wrong and harmful, yet they continued to support it to maintain their position and identity. They knew it was wrong, and they wanted their kids to be different. If they confronted themselves, they would have changed the society instead of fortifying the hate.

We can read “The Monsters!” in a a few different ways, and, like other EC Comics stories, it provides us with insight into ourselves and our society. It subversively calls out white supremacy without overtly presenting it in the story. To what extent this tactic proved effective, I don’t know. I do know, though, that “The Monsters!” and the other stories I have discussed recently point out the harm that racism, segregation, and white supremacy cause, not just on those under its boot but on those who wield the boot.

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.bsky.social.