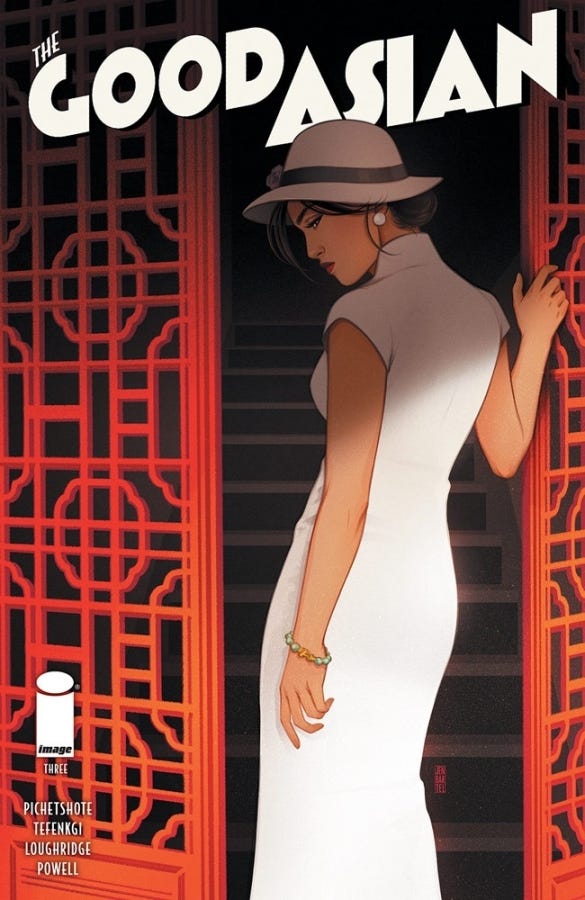

Last post, I looked at the first few pages of Pornsak Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefengki’s The Good Asian, specifically the ways that the pages foreground a lot of the themes throughout the series. Today, I want to continue that examination by looking at the first page of issue #3. These pages, likes the first two in the series, highlight the historical aspects of The Good Asian, notably the ways that the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act came into being and the ways that it impacted individuals decades afterwards, including during the setting of the series itself in 1936. This historical verisimilitude and research makes The Good Asian a powerful and important series that speaks both to the history of immigration in the United States and to the current moment.

The opening page of issue #3 contains two panels, with no border between them. The top panel shows Uncle Sam, in a vibrant red, white, and blue outfit, battling, along with other individuals behind him, a horde of grasshoppers that have the stereotypical faces of Chinese men with queue hairstyles. Uncle Sam shoves one of the racist caricature grasshoppers away with his left hand as he grabs the neck of another one that jumps in front of him. In the background, we see two other white men attacking the invading grasshoppers. The one on the left rears his fist back to punch a locust in the face and the one on the right uses a placard to bash the head of another locust. All of the colors in the panel are muted, except for Uncle Sam’s clothes.

Over this image, the narration reads, “By the 1870s, so many Chinese people were working on farms and factories for PENNIES, Americans blamed THEM for driving down worker rages.” Here, the narration points out that Americans, specifically white Americans, didn’t like Chinese immigrants working for cheaper wages because it drove down their own wages, causing the wealthy capitalists to exploit all of the labor that worked to make them wealthier. The narration continues, “As a result, anti-Chinese RIOTS erupted across America.” What sparked all of this? While anti-Chinese sentiment existed, the depression of the 1870s led to large unemployment and a stagnant economy, thus causing large swaths of individuals to find themselves without wages. Thus, instead of confronting the system the owners of the factories and business for exploiting them, they turned to Chines immigrants whom they argued were stealing their jobs and wages.

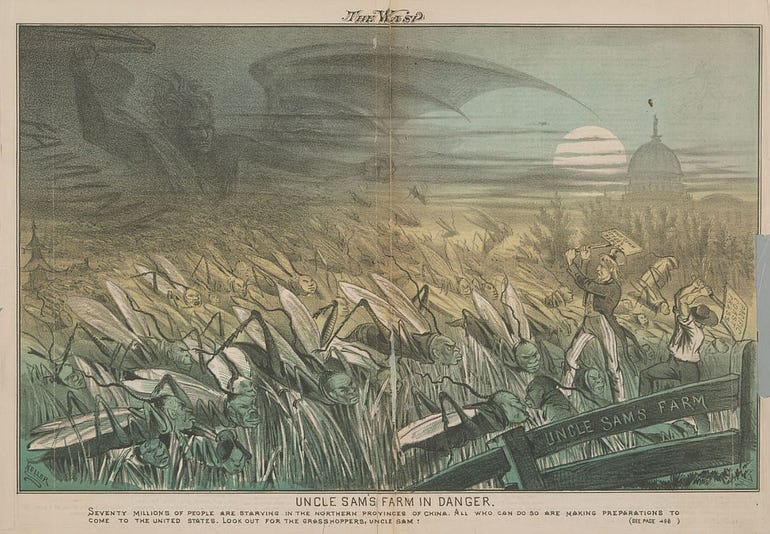

The strinking imagery of this panel stands out, but when we see that it has a real historical antecedent, the panel becomes even more powerful. Pitchetshote points out that the “panel is actually based on George F. Keller’s illustration ‘Uncle Sam’s Farm’s in Danger.’” This illustration originally appeared in the March 9, 1878 issue of The San Francisco Wasp, a satirical magazine that published ant-Asian and specifically ant-Chinese items. Keller’s illustration highlights this because it depicts Chinese immigrants and laborers as grasshoppers, coming to wreak havoc on the fields of American farmers. Pitchetshote also notes that the illustration appeared as a commentary and reaction “to the a famine in China that the paper feared would lead to millions of Chinese immigrants invading America.”

What stands out, for me, when looking at Keller’s image is how much it makes me think about John Gast’s 1872 painting American Progress which depicts Columbia leading settlers to the West, bringing civilization into the dark and uncivilized lands. In this painting, the entire left side of the painting sits under dark clouds, as if the Indigenous population, who flee in the face of the settlers, have no civilization or light. The right side, depicting American progress, appears under the sun, as if they are bringing light to a darkened world. Keller’s illustration contains a similar set up, but instead of fleering, the Chinese immigrants bring darkness and foreboding to the “civilized” society in the United States. We see this with the dark clouds from the left even reaching to the United States Capital, as clouds begin to cover the sun that shines down on the building.

From the left side of the image, famine, whip in hand, pushes the hordes of grasshoppers forward as they overrun Uncle Sam’s Farm. In the farm, Uncle Same stands poised to defend his farm, as the “Pacific Coast Press” stands behind him, ready to assist in any way possible. This image plays on stereotypes and xenophobia, depicting immigrants, who are actively seeking a better life and escaping famine, as hordes of insects looking to devour anything in their path. It’s an age old trope, demonizing and dehumanizing others instead of pointing the finger and blame at those who actually cause the problems that lead to low wages, unemployment, and economic stagnation. The San Francisco Wasp, when describing Keller’s illustration, make all of this abundantly clear through their use of dehumanizing and demonizing language. They write,

Our artist has represented the possible immigration as a swarm of grasshoppers driven along by the inexorable hand of Famine…Uncle Sam, armed with the House Committee Resolutions, assisted by his hired man, the California Press, is striving to stay the torrent of yellow grasshoppers. It seems almost impossible for them to succeed; and it is certain that they will be overcome by the invader unless assistance of a more substantial kind be rendered.

These two sentences contain multiple words that present the immigrants as a threat, from comparing them to “a swarm of grasshoppers” and more specially a “torrent of yellow grasshoppers” to stating that Uncles Sam and his “hired man” will certainly “be overcome by the invader” unless the government does something. To pass the blame, the wealthy, as we know, seek to drive a wedge between individuals, labeling them as invaders or threats or a horde. In this manner, they dehumanize individuals, making it easy for others to attack them.

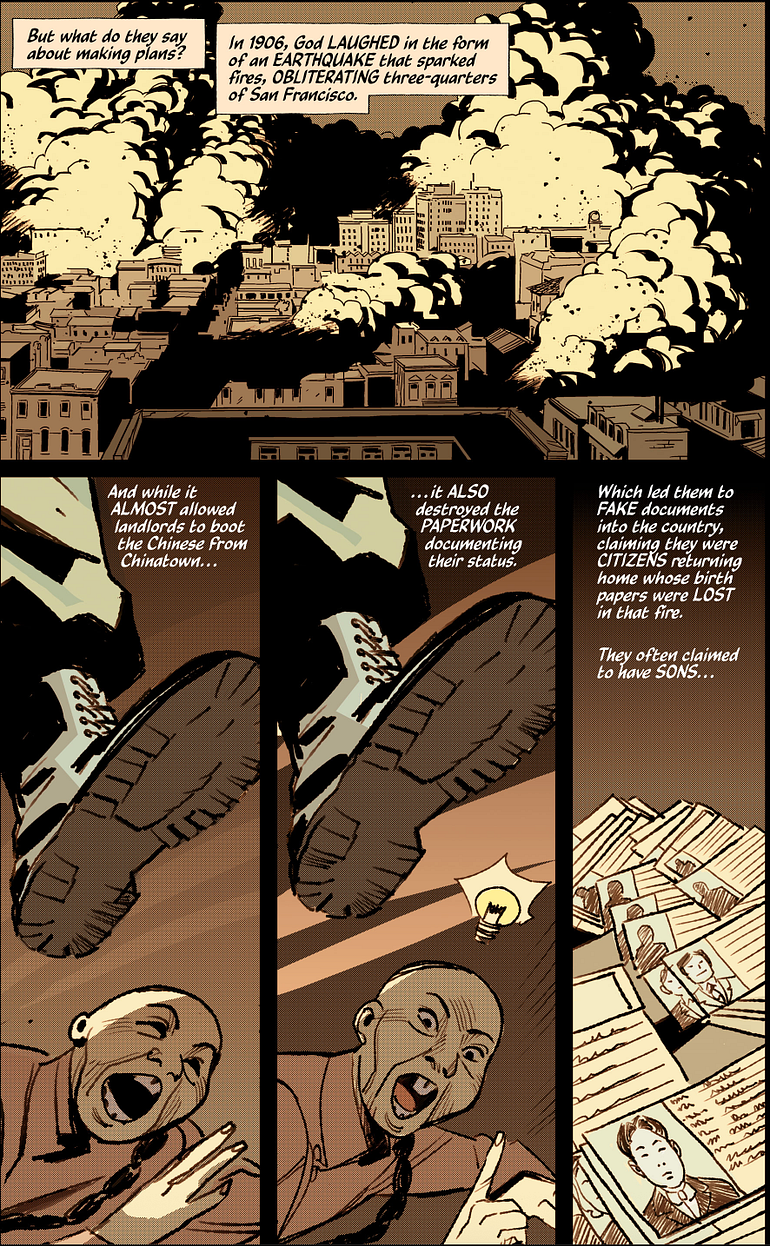

This type of rhetoric led to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, as the narration under the opening panel in issue #3 highlights. That act, the narration continues, “forbade ALL Chinese people from entering American, except, EVENTUALLY — Diplomats. Merchants. Students. U.S. Citizens. (Women ONLY entering if they were FAMILY to men of those categories.)” Almost 25 years later, with the exclusion act ingrained into the fabric of the nation, the 1906 San Francisco earthquake happened, destroying around two-thirds of the city. This act of nature led to even more discrimination, as the city officials sought to use the earthquake as a chance to eliminate Chinatown and move the Chinese population to the outskirts of city, where they could still pay taxes but would be removed from the city itself.

The second page of issue #3 depicts this, and the three panels at the bottom drive home what happened. In the first two, we see a disembodied boot descending onto the head of Chinese man as the narrator points out that landlords sought “to boot the Chinese from Chinatown.” In the second panel, still underneath the boot, the man has an idea, and a lightbulb appears above his head. He thinks that since the earthquake “destroyed the PAPERWORK documenting their status” they could create fake documents in order to stay and work. It becomes a moment of resistance underneath the boot of the state and xenophobia. It becomes a moment that subverts Uncle Sam and the rhetoric surrounding infestation.

While The Good Asian centers on Edison Hark’s search for Ivy Chen to unravel crimes across Chinatown, it is much more than that. The series engages with history and the present in ways that make us think about the past and the present and how they inform one another. I could spend multiple posts on The Good Asian, but I will leave it here for now. What are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.