In order to understand the present and prepare for the future, we must understand the past and the ways that the past impact the present. As Frederick Douglas put it in his 1852 speech What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?, “We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future.” When we deny students the opportunity to learn about the nation’s past, warts and all, we deny them the ability to fully understand and navigate the present. As James Loewen puts it, “The upbeat happy endings in our textbooks send a message about history itself.” That message is that the past happened and it has not impact on the present.

Loewen and Nate Powell drive this home in the graphic adaptation of Lies My Teacher Told Me, specifically at the end of chapter 11, “History and the Future,” where Powell depicts two scenes from history. The first shows police violently attacking marchers during the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965, and the second shows insurrectionists attacking the United States Capital on January 6th. The captions under each image read “Violent subversion of democracy,” with 1965 and 2021 under each panel respectively. Over these images, Loewen writes, “By avoiding serious discussions of events and trends in our past, and by implying that no real thinking about our history needs to be done, textbook authors suggest that our past has no effect on our future.” Through these images, Loewen and Powell highlight the various ways that individuals have tried to subvert democracy and also the linkages of white supremacy that did not automatically disappear at the end of the Civil Rights Movement.

We rely on “historical closure,” as Angela Davis calls it, to make ourselves feel better about the past and the present. By framing ideas and events from the past as closed, we present them as having no impact on the present. We present them as dead and buried, things to be discussed as if they no longer walk the earth with us. In doing this, we refuse to engage with them, viewing ourselves as cured and superior, as if the ideas did not carry forward through the generations, mutating and spreading because we refuse to adequately confront them. Martin Luther King, Jr. understood this. In his posthmous “A Testament of Hope” (1969), King wrote, “Many whites hasten to congratulate themselves on what little progress we Negroes have made. I’m sure that most whites felt with the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, all race problems were automatically solved. Because most white people are so far removed from the life of the average Negro, there has been little to challenge this assumption. Yet Negroes continue to live with racism every day.”

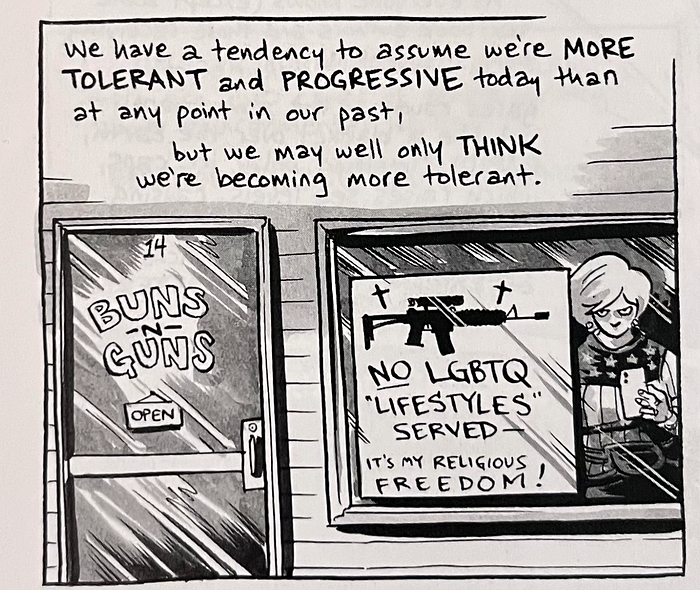

Ideas don’t disappear. They remain. Even though an event happened in the past, the ideas that sparked that event stay. White supremacists didn’t disappear with the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. Anti-LGBTQ individuals didn’t disappear after Obergefell in 2015. Antisemitism didn’t start with the Nazis and it didn’t disappear after Nuremberg. Adherents to slavery didn’t skulk into the sunset after the Civil War. In our refusal to tell students about these events and ideas, we hinder their ability to confront them in the present.

I’ve known, for a while, the connections between the ways that Jim Crow and the United States impacted the rise of Nazism in Germany and how the rise of the Nazis mirrors our current moment. Yet, as I watched Hitler and the Nazis: Evil on Trial, I kept thinking about the similarities, from Franz von Papen and Paul von Hindenberg thinking they could control Hitler just as the Republican Party sought to control or minimize Donald Trump. I thought about how the Nazis telegraphed, overtly, what they planned to do, but no one really pushed to stop them and how Trump does the same while news networks showcase right wing politicians without question. I thought about the cult of personality. I thought abut how Josef Goebbels coached Hitler for his speeches, making audiences wait thirty minutes or more for Hitler to appear and how Trump does the same, even the rhetorical flourishes and motions. There are more correlations with everything from Hitler’s conviction after the failed Munich Beer Hall Putsch to the revenge of the Knight of Long Knives.

While I see these things, many don’t. especially students because they get limited information about the past and get taught that America is perpetually moving forward, progressing towards an ideal society. Loewen, over an panel where Powell depicts a white mother and daughter eating next to a Black father and daughter in a restaurant, writes, “[Textbooks] celebration of eternal progress misleads students into a narrative in which racial inequality has consistently improved in our history, with no steps backward.” This false narrative allows complacency; it allows for the belief that we, as a society, are “more tolerant and progressive today than at any point in our past” while individuals vociferously rail against immigrants, LGBTQ individuals, Blacks, women, and more.

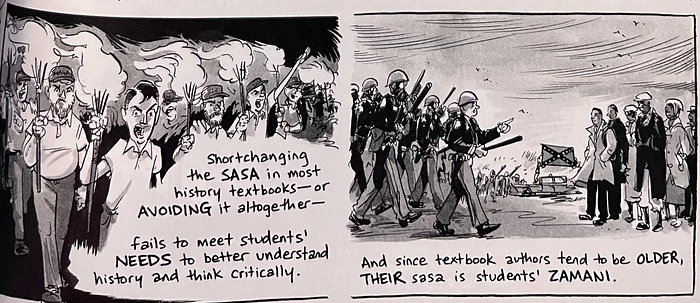

Loewen points out that “[m]any African societies divide humans into three categories: those still alive on the earth, the Sasa, and the Zamani. The Sasa may be deceased, but they live on in the memories of those still living . . . when the last person to know an ancestor dies, that ancestor leaves the Sasa for the Zamani, the dead, not forgotten but revered outside of living memory.” History textbooks shortchange the historical Sasa, and in doing so, they fail “to meet students’ needs to better understand history and think critically.” They fail to connect the Zamani, the events further removed from students, to the Sasa and the present. Through this, they disadvantage students and stifle critical thinking, suppressing individuals in the process.

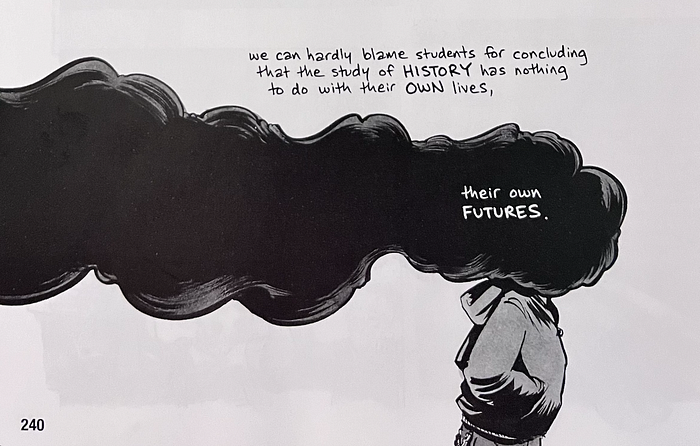

By failing to provide links between the past, the present, and the future, and by hampering students’ ability to think critically, we deny students and society the ability to escape the past and to move forward. “As long as these connections are buried,” Loewen writes, “we can hardly blame students for concluding that the study of history has nothing to do with their own lives, their own futures.” History has everything to do with our lives and our futures because what we learn or don’t learn from history inpacts us today and tomorrow. By denying connections between the past and present, we lead students and society into a foggy future, as Powell depicts the student at the end of chapter 12, walking to the right side of the page as a dark cloud of smoke envelops their head. The student walks blindly into the future, not thinking about the ways that the past influences them in this moment.

Until individuals critically engage with the world around them, drawing connections, we will be like the student, blinded by fog, unable to see a foot in front of our faces. We will stumble along, telling ourselves we have progressed but really finding news ways of repeating all of the atrocities of the past. We must reckon with history. We must reckon with the myths we tell ourselves. Until we do that, we will continue to remain blind to the issues that hinder progress towards a more equitable and equal society.

What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Twitter @silaslapham.