Over the past few weeks, I’ve been thinking about constructing a fascism in literature syllabus. Right now, I keep going back and forth on whether or not to focus specifically on American literature or to expand it and make it a world literature course. For this post, I am doing the latter because I feel that reading novels about fascism in a broader context will be helpful for understanding fascism in the United States. With that in mind, I will have a length list of primary texts in this syllabus, and I would not be able to cover all of these texts in one course. However, I want to provide this list for readers so that they can choose what texts that might want to add for a course or just what texts they may want to read. Finally, I will present this list in chronological rather than alphabetical order.

Course Overview

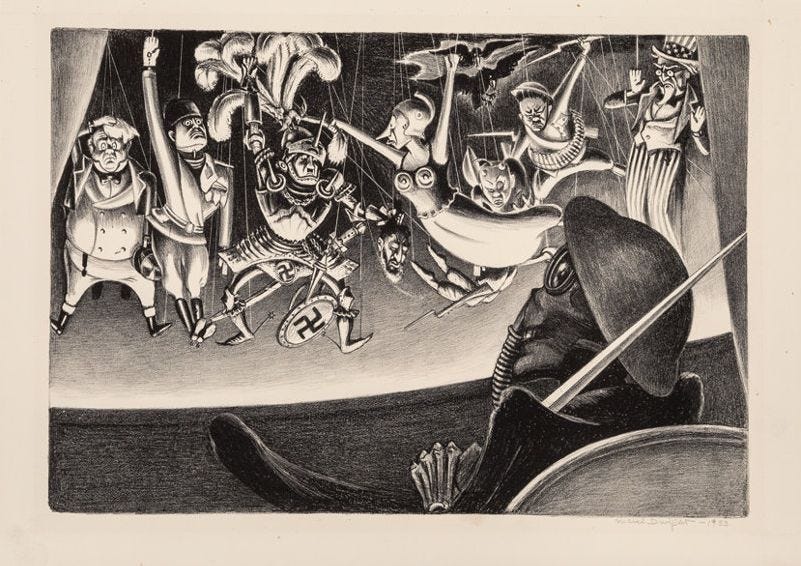

When we think about fascism, our mind immediately goes to Italy’s Benito Mussolini or Germany’s Adolf Hitler and the Nazis following World War I. However, we rarely think about fascism’s progenitors in the United States, the seeds that provided the groundwork. Robert Paxton, in The Anatomy of Fascism, claims that “the earliest phenomenon that can be functionally related to fascism is American: the Ku Klux Klan.” Paxton points out the tha first Klan’s appearance in the aftermath of the Civil War “constituted an alternate civic authority, parallel to the legal state, which in the eyes of the Klan’s founders, no longer defended their community’s legitimate concerns.” With this in mind, this course will explore fascism in literature, focusing on the United States but also expanding outwards across the globe to Europe and to Asia. There are not many novels about fascism in Japan; however, there are resources we will examine about fascism in Asia.

Countless intellectuals have defined fascism, and we will begin the course by reading the definitions of fascism that Umberto Eco, Toni Morrison, and Jason Stanley provide, thus creating a foundation from which to examine the novels that we will read over the course of the semester. Each of these writers define fascism in similar yet also slightly different ways, but each comes back to a key tenant of fascism, the construction of a mythic past that never truly existed in the first place. In How Fascism Works, Stanley begins by stating, “Fascist politics invokes a pure mythic past tragically destroyed.” This mythic past includes a patriarchal society, a glorious nation state, a virile populace, a warrior class, and more, all wrapped in the cloak of a false nationalistic narrative.

For this course, we could begin with texts that glorify the mythic past of the Confederacy, texts that create the Lost Cause narrative. We could read Thomas Dixon, Joel Chandler Harris, Margaret Mitchell, and others who look back to that mythic, non-existent past and glorify the Klan. However, instead of doing that, we will begin with Jack London’s 1908 dystopian novel The Iron Heel, a novel that George Orwell called “a very remarkable prophecy of the rise of fascism” and a novel that inspired his dystopian novel 1984. Beginning with London, we will trace fascism in literature, focusing primarily on the United States at first then moving globally.

Along with London, we will read Sinclair Lewis It Can’t Happen Here (1935), a novel written two years after the Nazis came to power in 1933 and a novel that details the rise of fascism in the United States. We will also read Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), a novel about the suppression of knowledge through the burning of books; Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1962), an alternative history novel that imagines what would have happened if the Axis won the war; Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993), a novel about what happens when we ignore the rise of fascism and the impacts it has on future generations; Philp Roth’s The Plot Against America (2004), an alternate history novel that addresses what could have happened if fascists took over the United States government; and Silas House’s Lark Ascending (2022), a dystopian novel about the collapse of society and government after a fascist takeover.

Moving beyond the United States, we will look at the rise of fascism in Europe specifically, starting with dystopian novels such as Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (1924) and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) before moving into post-1933 works such as Katharine Burdekin’s Swastika Night (1937), Arthur Koestler Darkness at Noon (1940), Anna Seghers’ The Seventh Cross (1942) and other works. We’ll conclude with novels such as George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale (1985). We cannot cover every text, but these texts will provide us with a foundation of works that confront fascism head on and whose “task,” as Ta-Nehisi Coates tells his students in The Message, “is nothing less than doing their part to save the world.”

Primary Foundational Texts:

*Arendt, Hannah. Selections

*Eco, Umberto. “Ur-Fascism”

*Morrison, Toni. “Racism and Fascism”

* Paxton, Robert. Selection from The Anatomy of Fascism

* Snyder, Timothy and Nora Krug. On Tyranny

*Stanley, Jason. How Fascism Works

Primary Texts American (chronological order):

*London, Jack. The Iron Heel (1908)

*Lewis, Sinclair. It Can’t Happen Here (1935)

*Steinbeck, John. The Moon is Down (1942)

*Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451 (1953)

*Vonnegut, Kurt. Mother Night (1961)

*Dick, Philip K. The Man in the High Castle (1962)

*Spiegelman, Art. The Complete Maus (1986)

*Butler, Octavia. Parable of the Sower (1983)

*Williams, John. Clifford’s Blues (1999)

*Roth, Philip. The Plot Against America (2004)

*Lutes, Jason. Berlin (2018)

*Orringer, Julie. The Flight Portfolio (2019)

* Clark, P. Djèlí. Ring Shout (2021)

*Campbell, Bill and Bizhan Khodabandeh The Day the Klan Came to Town (2021)

*House, Silas. Lark Ascending (2022)

Primary Texts Global (chronological order):

*Zamyatin, Yevgeny. We (1924)

* Huxley, Aldous. Brave New World (1932)

*Burdekin, Katharine. Swastika Night (1937)

*Koestler, Arthur. Darkness at Noon (1940)

*Seghers, Anna. The Seventh Cross (1942)

*Levi, Carlo. Christ Stopped at Eboli (1945)

*Serge, Victor. Last Times (1946)

*Reck-Malleczewen, Friedrich. Diary of a Man in Despair (1947)

*Orwell, George. 1984 (1949)

*Debreczeni, József. Cold Crematorium: Reporting from the Land of Auschwitz (1950)

*Ginzburg, Natalia. Family Lexicon (1963)

*Szabó, Magda. Katalin Street (1969)

*Atwood, Margaret. The Handmaid’s Tale (1985)

*James, P.D. The Children of Men (1992)

*Harris, Robert. Fatherland (1992)

What literature would you add? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham