The generational trauma of oppression impacts everyone involved: the oppressed and the oppressor alike. While the trauma does not impact each in the same manner, it creates psychological trauma that each must endure. Lillian Smith points this out in Killers of the Dream when she writes “that the warped, distorted frame we have put around every negro child from birth is around every white child also.” Throughout her memoir, Smith details the psychological impact that living in a white supremacist system had on herself as well as other whites in the South.

While Smith directly confronts white supremacy, she also humanizes individuals from the teenager who tells Smith that she knows what is right but she is afraid to do it because of what people will think to Smith’s parents who teach her to love Jesus but also tell her that she is better than a Black person. In fact, Smith dedicates Killers of the Dream to her parents, writing, “In memory of my Mother and Father who valiantly tried to keep their nine children in touch with wholeness even though reared in a segregated culture.”

Her parents, while engaged within a segregated society, also push Smith forward, urging her to change the future. Her father tells her that some of her ancestors were enslavers, but he also tells her “that was your grandfather’s fault, not yours. The past has been lived. It is gone. The future is yours.” He concludes by asking her, “What are you going to do with it?” This is the same thing that Smith tells the teenager when she says, “You have to remember . . . that the trouble we ware in started long ago. Your parents didn’t make it, nor I. We were born into it.” Even though we were “born into it,” Smith asks the girl what she will do to break the cycle.

Like Smith, Nora Krug examines generational guilt and trauma in her graphic memoir Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home by tracing her grandfathers’ and uncles’ involvement with the Nazis in World War II. Over the course of her journey, Krug humanizes her ancestors. Instead of presenting them as malignantly evil or faceless abstractions, the latter of which I think about in relation to the opening scene of Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, Krug humanizes them through letters, photos, and other tangible items.

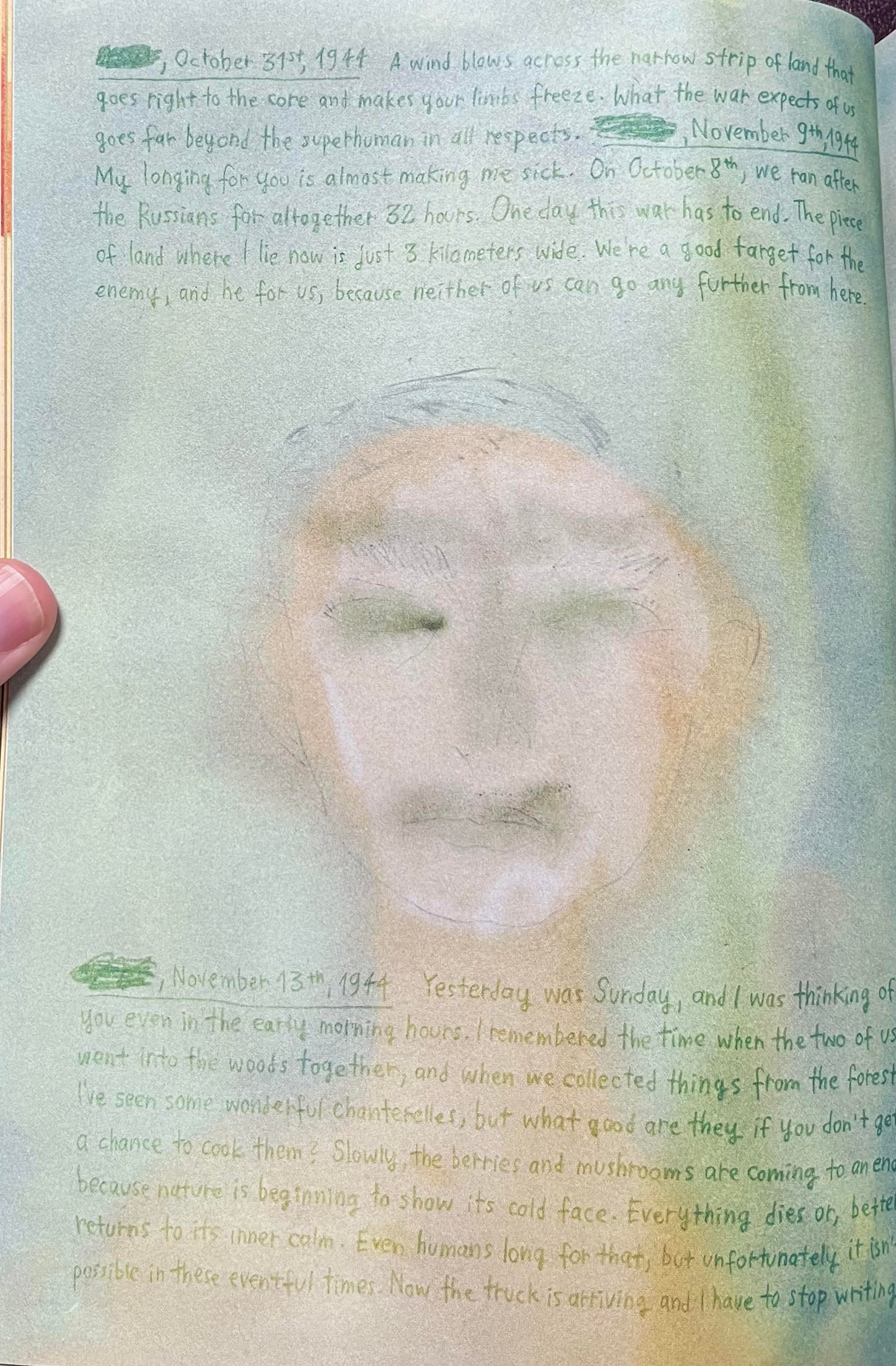

At one point, Krug receives a package which contains letters from Edwin, her grandfather Willi’s brother, to his wife Elsa. Edwin writes to Elsa about his loneliness and missing her and his family. They are, as Krug writes, “adorned with drawings and pressed leaves and flowers, with place names censored by the military, sent from what he describes as the land of ‘fathomless forests, swamps, and steppes,’ [and they] chronicle nothing but his gradual emotional disintegration.”

Krug provides excerpts from 10 of Edwin’s letters between May 23, 1944 to November 13, 1944. She couples these excerpts, over three pages, with a fading sketch of Edwin which resides in the center of each page. On each subsequent page, as with each subsequent letter, Edwin’s face fades into the page, become an abstract image as the words slowly fade into the background beneath it. The final page contains a letter, dated December 28, 1944, to Edwin’s family saying that he has been missing since November 18. Over these three pages, Krug highlights Edwin’s humanity through his descriptions of the most beautiful sunrise he said he has ever seen to the smells and sounds he experiences. Krug presents him as Elsa’s loving husband, as a man connected with nature, who served on the frontlines on the Eastern front. She does not, again, glamorize him, but she humanizes him. He is not an abstraction, a punchable and interchangeable face for Indiana Jones to waylay or for me to shoot as I virtually storm the beaches of Normandy.

Interspersed throughout Belonging, Krug shows the reader items she picked up at flea markets. After a section where she shows her uncle Franz-Karl’s school compositions, highlighting how he became indoctrinated into Nazi ideology, she presents a myriad of items she calls “Child’s Play” that she picked up at the markets. These items include stereotypical caricatures of Jews, children’s books, Hitler Youth trading cards, and other items. In others, she shows postcards from prisoners of war, postcards from family members under allied bombings, and other items. Along with all of these items, Krug presents readers with soldiers in times of play, playing with dogs, lounging in the grass, or in other moments of joy. By showing these items, Krug, again, humanizes them, showing them as individuals like all of us, enjoying their leisure and life.

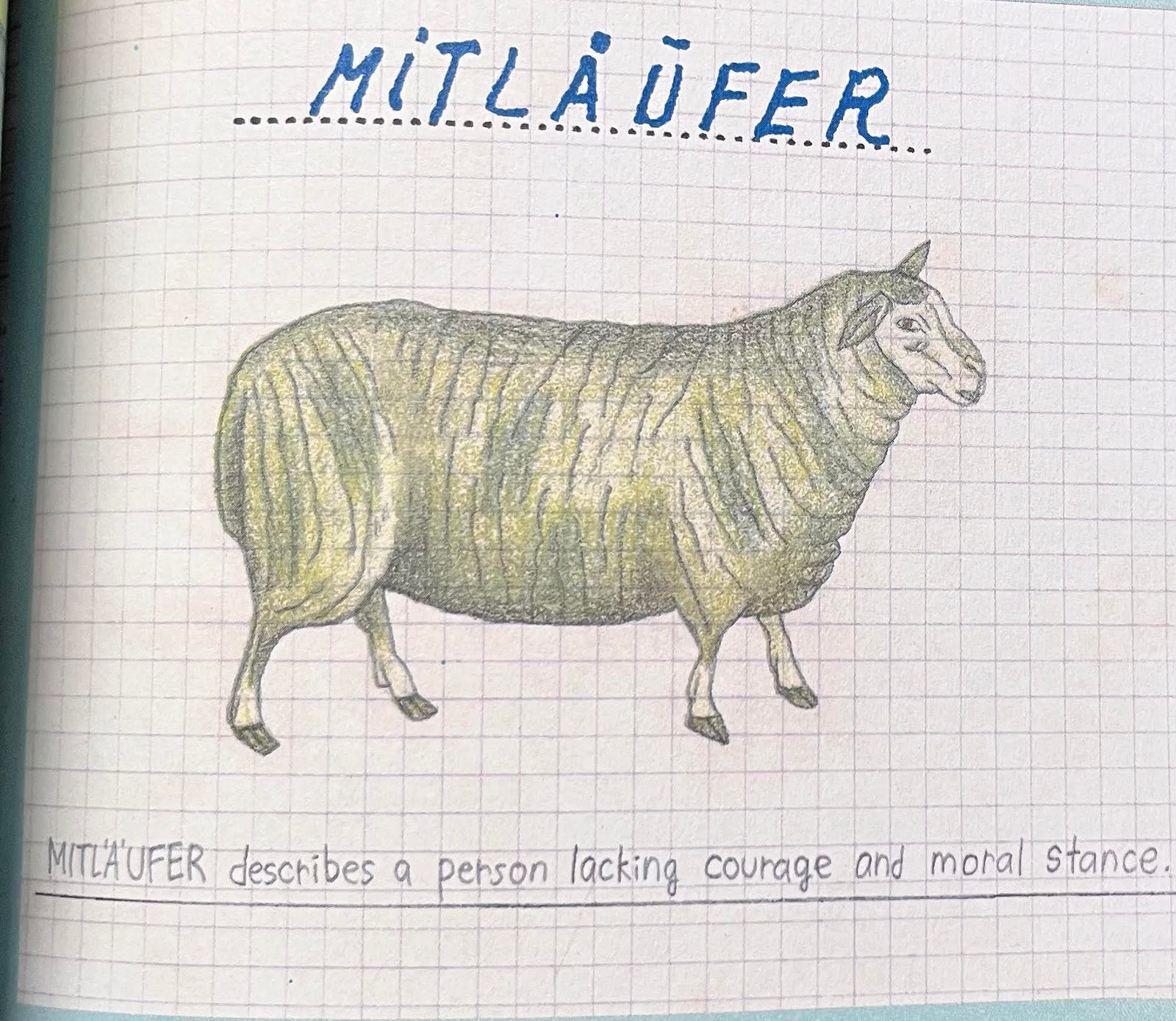

The way that Krug humanizes individuals in Belonging calls us to question our own selves and the ease with which someone can succumb to such virulent ideologies. Some, like Krug’s grandfather, merely became mitläufer while others full throatily endorsed the virulent, Nazi ideologies. How does one differ one form the other? Walking down the street, can one do such a thing? Yet, both are human. Both are individuals with family and loved ones. With joys. With sorrows. With dreams. With desires. Both are us but not us.

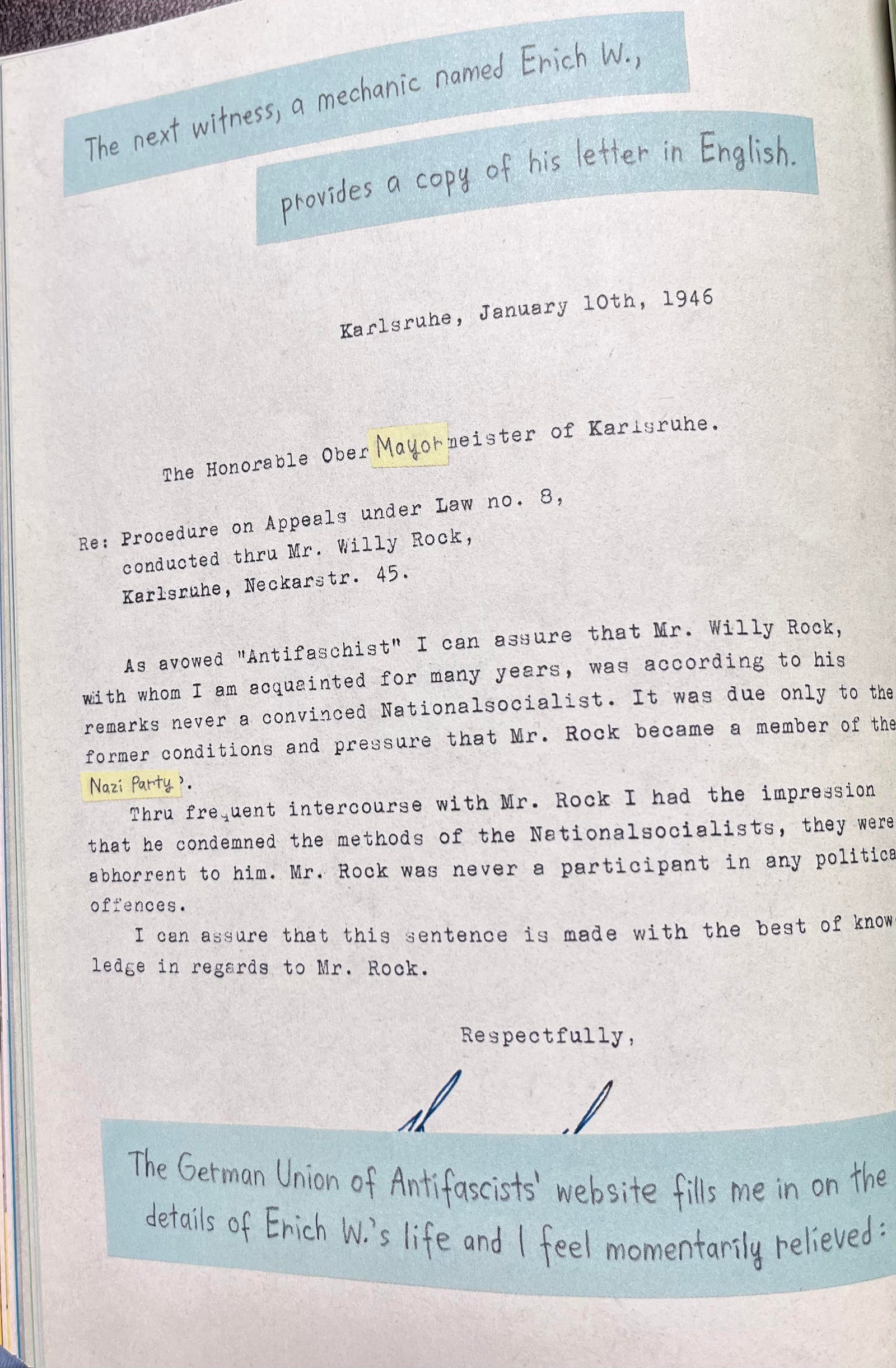

Krug’s journey to discover her grandfather Willi’s role in all of this highlights this ambiguity because he did not, it seems, adhere to Nazi ideology, yet he participated in the Wehrmacht to ensure the safety of his family and himself. After the war, the Allied troops deem Willi an “offender,” one step below the most notorious “major offender.” Krug, reading through the archives, sees the struggle Willi goes through to show that he was a mitläufer not an “offender.” There are countless letters, from the mayor of Karlsruhe to a letter from an “avowed ‘Antifaschist’” Erich W. to a letter from Albert W. whose wife was Jewish. Willi’s plight from “offender” to mitläufer drives home the humanness of his experience and the humanness of others’ experiences.

Writing about her arrival in West Germany in the early 1960s, Angela Davis points out that she did not know whether or not someone adhered to Nazi ideology or not. She writes, “half the people I saw on the streets, and practically all the adults, had gone through the experience of Hitler. And in West Germany, unlike the German Democratic Republic, there had been no determined campaign to attack the fascist and racist attitudes that had become so deeply embedded.” Even if the people did not participate, she notes that the ideas remain. The fertile soil for rebirth, regrowth remains underneath the feet of these individuals who are human just like you, just like me, just like Lillian Smith’s parents.

Krug, Smith, Davis, Hannah Arendt, Anna Seghers, and others all explore the ways that individuals get wrapped up in virulent ideologies and descend into violence and oppression, either by directly engaging or passively ignoring it. What all of these thinkers show is that no one is immune. Each of us can succumb, diving into the depths of violence and becoming the oppressor. When we make an enemy out of others, as Smith points out, that descent becomes easier. We must remain ever vigilant of ourselves and not succumb, because when we demonize others, we make them into enemies.

There is so much more that I am working through right now, but I will leave it here. What are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.