This semester, in my “Monsters, Race, and Comics” course, I’m teaching the first two volumes of Rodney Barnes and Jason Shawn Alexander’s Killadelphia. Recently, I just reread both volumes, which contain the first 12 issues of the series. There is a lot within these issues that, combined with everything else we read this semester, I want to explore with students. Specifically, I want to have them think about the role of vampires and vampirism within the series. I want them to think about the existential questions of our very existence. I want them to think about the thread of hope that runs throughout the series. I want them to think about the generational interactions between the characters, notably James Sangster, Jr. and his father and Estelle and Tevin. Along with all of this, I want them to explore the role that history plays within the series, and it is this last point that I want to briefly touch on in today’s post.

The story at the center of Killadelphia involves John and Abigail Adams becoming vampires and existing to the present day. They see what the United States has become, and they each feel, with different viewpoints, that a better path could be paved for the nation. They see the ways that the systems have failed a large portion of the citizenry, and they want to raise up a vampire army to rectify the past. James Sangster, Sr. becomes a vampire, and his son, James Sangster, Jr. brings his father back to fight the Adamses. That doesn’t explain everything, I know, but in a nutshell that’s what’s happening in Killadelphia.

I don’t want to focus on the overall narrative arc of the first two volumes, mainly because it contains a lot. Instead, I want to focus on one character, Jupiter, specifically on the varying ways we get Jupiter’s backstory. The two versions of Jupiter’s history come from Abigail, Thomas Jefferson, and Jupiter himself. Abigail introduces us to Jupiter in issue 7 as she sits around the table with her crew talking about the ways that capital controls America. She tells those around her a story, a story about Jupiter.

In 1814, after their return from the Caribbean, John wants to reconcile with his adversaries, and he has a dinner with Thomas Jefferson. Abigail doesn’t want to take part in “bullshit” discussions and platitudes, so she walks outside and sees Jupiter working on a wagon wheel. He wears a halo collar and an iron bit. Abigail says that he seemed “robotic,” going about his task with no emotion. When done, she says, “He voluntarily returned to his subjugation.” Jupiter’s demeanor intrigues Abigail, and when she goes back inside she asks Jefferson about Jupiter. Jefferson tells her that they used to play, as children, all day long. “One could almost say,” Jefferson tells Abigail, “Jupiter was my best friend.” The “almost” here carries a lot of weight, as Jefferson explains, because it “speaks to the boundaries of such a relationship. Took him some time to accept his station in life and that favor and friendship are two entirely different things.”

Along with the dialogue from Jefferson, the juxtaposing panels depicting Jefferson and Jupiter are important. As he describes their childhood “friendship,” we see a young Jupiter smiling as he pushes Jefferson on a swing. The next panel, where Jupiter learns his “station,” depicts a silhouette of Jefferson in the background swinging while in the foreground we see a white man, possibly an overseer, whipping the young Jupiter as his head hangs down. We move from “joyful” childhood “friendship” to separation, each moving into their “station” in life. Jefferson immediately follows this up by saying that Jupiter “hasn’t been the same since his family was sold off.” We don’t see this moment. Instead, we just see Jefferson telling this to Abigail. This shows Jefferson’s disregard for his “almost” friend and for those he and his family enslaved.

Abigail buys Jupiter from Jefferson, and she depicts him as a stoic man, succumbing to his subjugation. Jupiter keeps the halo on and wears the iron bit constantly. For Abigail, these acts “served as a reminder of his separation from the world.” However, Jupiter depicts this in a different way. Abigail turns him into a vampire to “free” him, but she does not “free” him because he serves as her enforcer of fear until he rises up against her during the attack on Philadelphia.

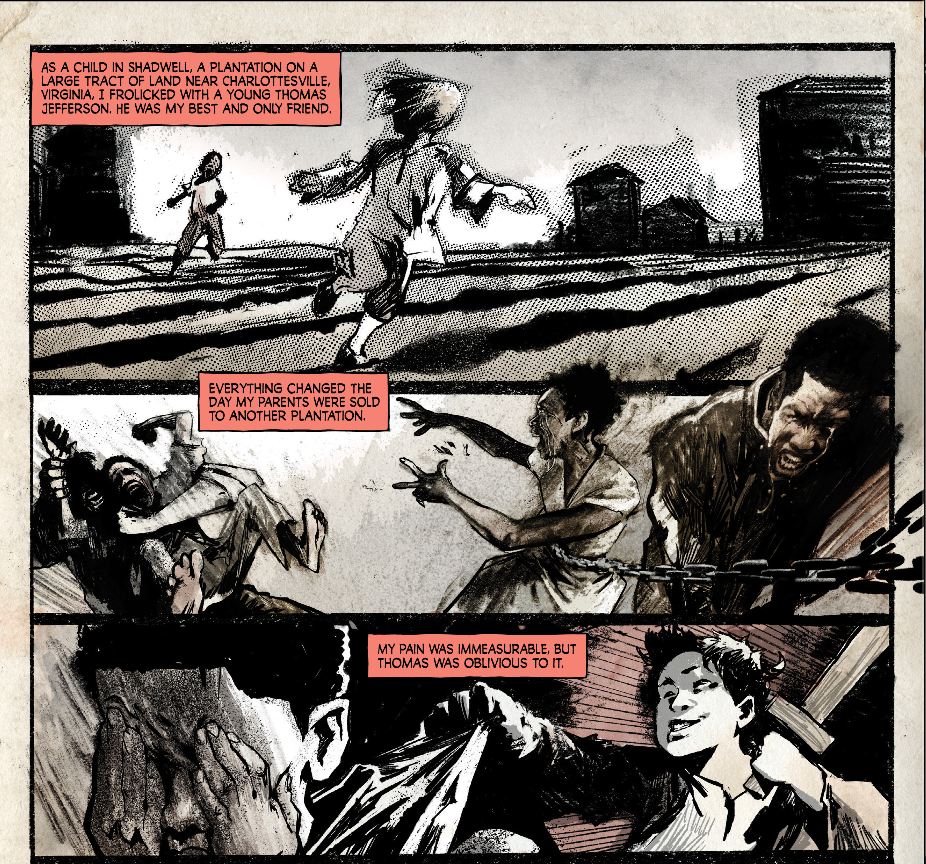

This image of Jupiter pushing Jefferson on the swing recurs later, as well, in Jupiter’s telling of his history. Whereas Jefferson, and by extension Abigail, depict Jupiter as joyful and happy playing with the young Jefferson, Jupiter depicts the events in a starkly different manner. This four-page sequence where Jupiter tells his own story begins similar to Jefferson’s telling. We see, in the first panel, Jupiter chasing Jefferson around Shadwell Plantation, and Jupiter says that Jefferson as his “best and only friend,” not his “almost” friend as Jefferson describes it.

Whereas Jefferson depicts the childhood “friendship” then Jupiter being whipped then offhandedly saying Jupiter changed after his family was sold away, Jupiter moves from the “friendship” to a panel depicting Jupiter’s family being sold. Someone, it’s unclear who, holds a screaming Jupiter back as his mother, being pulled by chains, reaches back towards her son. Here, Jupiter foregrounds the trauma of enslavement and the breaking apart of families. The third panel shows Jupiter crying, hands over his eyes, as Jefferson grabs his collar, wanting to play with his “friend.” Jupiter narrates, “My pain was immeasurable, but Thomas was oblivious to it.”

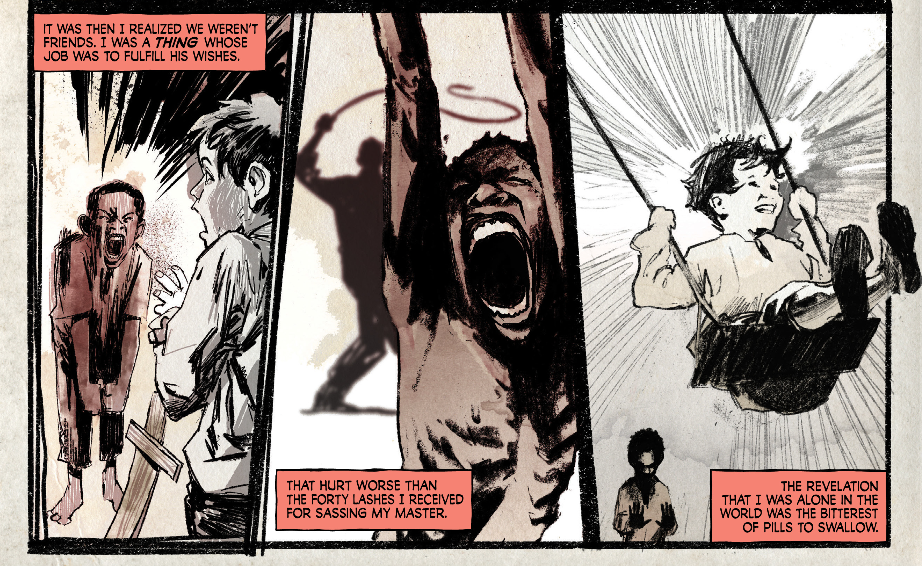

At this moment, Jupiter turns and screams at Jefferson, and Jefferson stands aghast. Jupiter tells us, “It was then I realized we weren’t friends. I was a thing whose job was to fulfill his wishes.” Whereas Jefferson, earlier, speculates on Jupiter’s learning his “station” and his change, Jupiter lays it all out, telling us it was the system of chattel slavery, and the ways that he, his family, and countless others existed not as humans but as “things,” as mere property for the pleasure and joy of their enslavers. This realization hurt Jupiter more than the whip.

The final panel of the sequence shows Jupiter, face down, in despair, hands out as if pushing Jefferson on the swing while Jefferson swings high in the air laughing. Here, we see a reversal of the initial narrative. While Jefferson’s recounting shows an exuberant Jupiter pushing his enslaver on the swing and both laugh almost uncontrollably, Jupiter shows his despair and anguish. He is not a silhouette, as Jefferson is in the second panel from his retelling, but Jupiter fades into the background of the panel at the bottom left, becoming smaller than his enslaver. Jefferson soars towards the forefront and right of the panel, and his foot, dangling from the swing, breaks the panel. Alexander’s depiction here, in many ways, highlights Jefferson’s ability to succeed, due to his wealth and race, while Jupiter remains in the background and restricted to the confines of the panel that cages him inside of it.

In the next post, I’ll finish this discussion looking at the rest of Jupiter’s narrative and its importance in highlighting the continued impact of enslavement to this day. Until then, what are your thoughts? Let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on twitter @silaslapham.