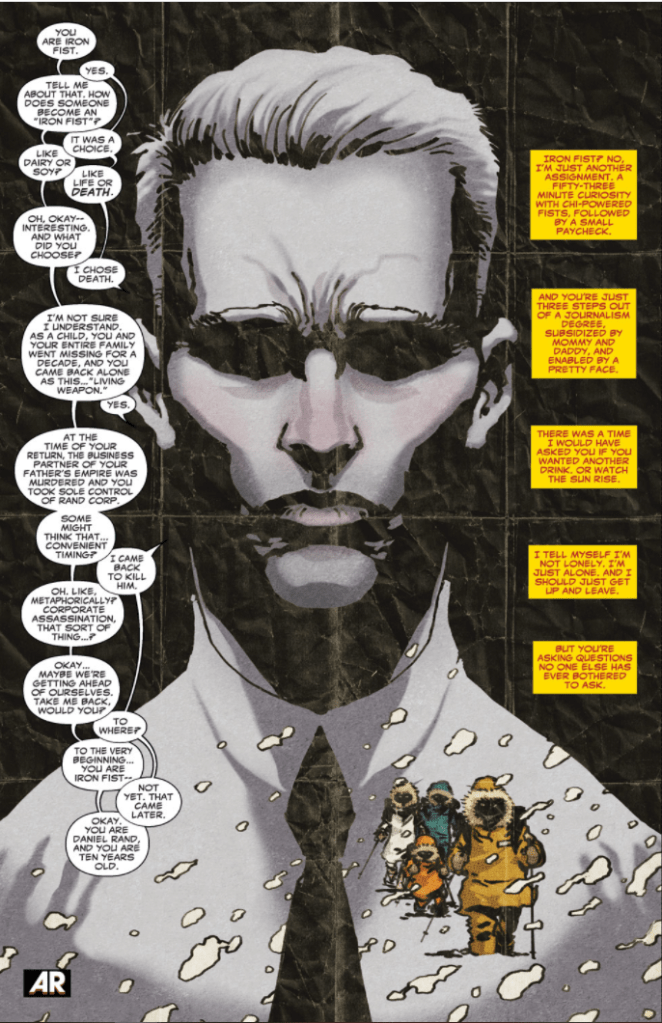

Ever since I first picked up trade versions of Kaare Andrews’ 2014 Iron Fist: The Living Weapon run, I’ve been enthralled. Initially, the artwork and Andrews’ commentary, throughout, on whiteness and capitalism really stood out. The latter is a theme that runs through his equally amazing Renato Jones: The One% (2016). Recently, I started rereading Iron Fist, and what really grabbed me this time was the opening page, a simple opening page that just shows Danny Rand in a shirt and tie, eyes and facial features shadowed in, and snow at the bottom flashing back to him, his mother, his father, and Harold Meachum walking through the mountains in search of K’un-Lun. The background looks like faded paper that has been folded multiple times. This a technique that Andrews’ uses in the series to indicate flashbacks. Today, I want to look at this page, dissecting it and thinking about what it does rhetorically.

When we read, we engage with the text, no matter the genre. We take part, as Lillian Smith puts it, in the “collaboration of the dream,” creating the experience alongside the author. Discussing the ways that she and her childhood friend Marjorie tell and listen to stories, Smith writes about the interactions between the author and the reader. She writes, “I think I rather remembered her as collaborating, and I would say, more actively than just listening because it was her story.” As Smith wove the stories, Marjorie actively engaged with them, creating within herself parts of the story, collaborating.

This collaboration occurs in any art form, but for me, comics, with their “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence,” serves as a medium where readers thoroughly engage with the “collaboration of the dream.” This occurs in many forms, as Scott McCloud points out, from filling in the action that occurs in the gutters to closure. I do not want to focus on those things; instead, I want to look at how comics, through the layouts that bring text and image together in a “deliberate sequence,” cause us to actively become part of the action. I’ve written about this some with reader positioning within panels, a feature that adds to this discussion.

I find the turning of the readers into an active participant in the “collaboration of the dream” on the first few pages of Iron Fist. The series begins, on the opening page, with Danny Rand relating part of his history. The series does shift back and forth between different characters narrating events, similar, to me, like the narration in an Ernest Gaines’ novel, specifically something like Of Love and Dust. On the first page, we have two separate speakers and two distinct voices in word bubbles and a voice in multiple shaded boxes . One of the speakers is Danny Rand. In the bubbles we see his speech, and in the boxes we see his narration. What we do not know, as we read this page, is who the other voice belongs to. We know, based on the questions, Danny’s answers, and his narration, that it’s a reporter; however, we do not see the reporter.

With this framing, the reader becomes the second voice. We look directly at Danny Rand and we ask him the questions. In this manner, we actively engage with the text. Danny, with the shadows layering his face, looks mysterious, not clear to us, and through the questions we get some information here and there. If we were merely the reporter, then we would not be able to see Danny’s thoughts, but on the page, we do. We see how he feels about us. Even though he answers our questions in a curt manner, he things about how we’re just here to grab the interview and make money. How we just graduated journalism school thanks to our parents and looks, and how in the past he would have asked us out. Now though, he merely feels lonely.

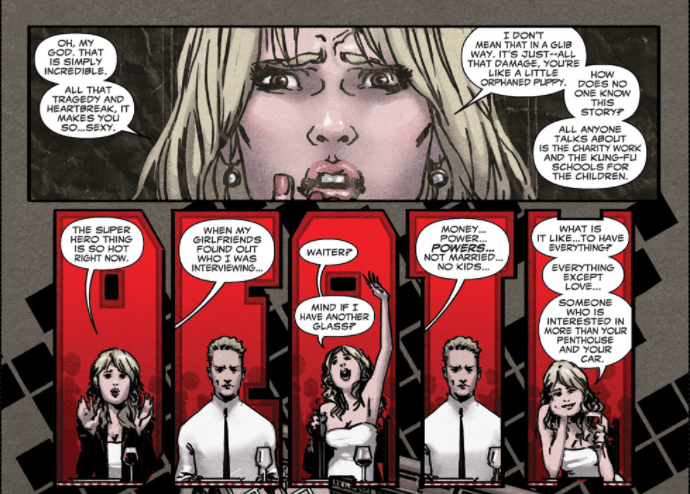

This positioning carries on for the first five pages of the series. After the opening page, we flashback to the expedition to find K’un-Lun and the avalanche that led to the death of Danny’s father and eventually his mother. Throughout these four pages, Danny relates the information to us, as if we’re a reporter, and we see the action and dialogue. After this sequence, we discover that the reporter is not us, the readers, it’s actually Brenda Swanson. Even with this revelation, though, we have become engaged within the narrative, initially positioning ourselves as the reporter, as collaborating in the creation of the dream which is the story. This positioning grabs us, hooking us, making us feel that like the Invisible Man in Ellison’s novel that Danny Rand is speaking directly to us and allowing us to actively engage and interact with him and his narrative.

Unlike the Invisible Man or other first person narrators in novels or short stories who directly address us as readers only through the words on the page, comics explicitly position us, both textually and visually, as the person that the the character addresses. We see this in film as well, but what differentiates comics from film is the fact that we do not passively sit by and imbibe what flashes across the screen. We actively fill in the textual and visual gaps. Any comic book series could be done in a manner that places us as an active participant in a text, and one way to do this is through placing us as interviewers. Gaines uses this frame work in The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman, and the frame gives way to Jane’s voice, much like Iron Fist gives way to multiple voices.

Ultimately, though, what this framing does is get us invested in the series, which is what the opening of any book aims to do. While we may not consciously think of ourselves as part of the story when we read the opening, we are part of it. We are collaborating with it, bringing ourselves to the narrative. The positioning as ourselves as active listeners and engagers with the characters only adds to this collaboration, leading us to think about ourselves in relation to the text.

Next post, I’ll look at some more aspects of Andrews’ Iron First series that really stand out . Until then, what are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below, and make sure to follow me on Twitter at @silaslapham.