I first read Pornsak Pichetshote and Aaron Campbell’s Infidel about five years ago, and after reading it, I decided to teach it in my “Monsters, Race, and Comics” course. Since I first read Infidel, I have picked up anything that Pichetshote has written, from Man’s Best and The Sandman Universe: Dead Boy Detectives to his writing and editorial work on The Horizon Project. I have always enjoyed his work, and when I first picked up issue #1 of The Good Asian at my local comic shop in 2021, I knew, from the moment I read the issue, that I would teach the series one day. The semester, I added Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefengki’s series to my “Lost Voices in American Literature” course, and as I reread the series for the third time, I am still blow away by Tefengki’s artwork and the conversations that The Good Asian opens up in the classroom, especially after finishing S. A. Cosby’s All the Sinners Bleed.

The Good Asian, plain and simple, is a noir story in the vein of Dashiell Hammet, Raymond Chandler, and Walter Mosely. Set in 1936 San Francisco, it follows Edison Hark, as Chinese-American detective, as he tracks down a killer who terrorizes Chinatown and San Francisco. The series, steeped in historical research, deals with anti-immigration and xenophobia, especially the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, both of which prohibited Chinese immigrants and restricted others from entering the United States. As well, the series deals with questions of race and identity, especially as Hark straddles two worlds as a Chinese-American who grows up in a wealthy, white family. All of this plays out in The Good Asian, but I don’t want to focus on that today. Instead, I want to take a look at some of the important moments in the series from an historic and illustrative perspective because, as I mentioned, Tefengki’s artwork and layouts add so much to this series.

The first three pages of The Good Asian serve as a primer in the power of sequential art to tell and story and to engage readers. The opening page contains a long horizontal panel at the top that proclaims “1936” in the middle with an image of the Golden Gate Bridge and Alcatraz depicted in the panel. The lone narration reads, “Gold.” From the outset, we know the year and the place the narrative takes place, and the use of “Gold” centers us in that place, bringing to mind the history of the Gold Rush in California and also the bridge itself. The rest of the page contains nine panels, laid out in a three by three sequence, with the narration moving through the panels. We see cars lined up on a street, a couple walking to a club as crowds wait outside, performers and dances inside the Jade Castle, a streetcar, and a man reading paper as he gets his shoes shined. The final panel zooms in on the man’s paper, and the headline reads, “GERMANY DECLARES MANDATORY DRAFT TO HITLER YOUTH.”

These images convey a vibrant, joyous scene, with people reveling in the nightlife, drinking, and dancing. Yet, the newspaper’s headline undercuts this boisterousness with a reminder of the international historical context. The series doesn’t touch, in any way, on Germany and the European context of the path towards World War II, but the use of this headline links what is happening in Germany, and what will happen, with the anti-immigration laws and xenophobia that The Good Asian addresses through Edison Hark and the Chinatown community. It points out that while America fought to save democracy from fascism it also enacted similar restrictions on individuals coming into and residing in the United States.

The narration over the course of the page drives this fact home too. Over the images of the nightlife, the narration reads, “Gold. Mention it, and boom — folks’ll forgive anything. Take San Francisco. The Golden Gate City. People get so distracted by the ‘golden,’ they ignore it’s a gate. They ignore why it’s a gate. ‘Cuz gates are built for piece of mind.” The narration points out the ways that entities try to, under the guise of safety and “peace of mind,” wall people off from one another. Lillian Smith pointed this out when she said, about her time as a missionary in China in the early 1920s and seeing the ways the British treated the Chinese. She writes,

I was young then. Young and inexperienced, and from a South where I had practiced segregation since I was born. But I saw what was happening. Seeing it happen in China made me know how ugly the same thing is in Dixie. I can never forget my deep sense of shock when I saw Christian missionaries from the South (and North, and England) impose their ideas of ‘white prestige’ on this people who were living on their own soil. Here we were, intruders, staying there only on sufferance, yet forever preening and priding ourselves on our white superiority and calling ourselves followers of Christ. It was this kind of thing that makes a young person sick. And I was young, and honest, and I was sickened by what I saw.

Smith understood that by using gates to protect one’s “peace of mind,” the gate walled off individuals, causing those it seeks to protect to succumb to psychological trauma stemming from their actions against those they seek to keep on the other side of the gate. The final panel, referencing Germany and the Nazis, hints at this too because it points out that while the United States recognizes the threat in Germany, it enacts its own violence against individuals who seek refuge and a life in its own nation.

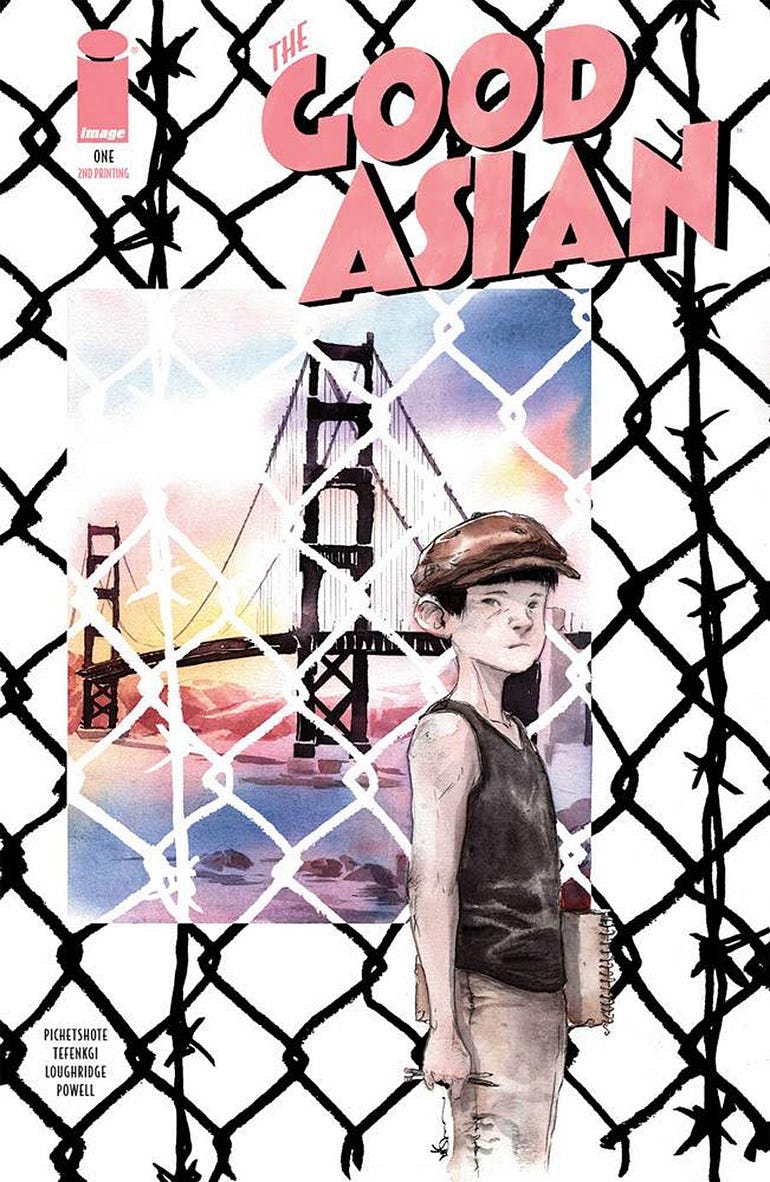

The next two-page spread drives all of this home as we see an immigration official asking a Chinese immigrant some of the 105 questions that the government required during such interviews. Tefengki surrounds the spread with barbed wire, choking off the page from the start and depicting a walled in scene. The spread contains six horizontal panels. Each panel is split in two, with the barbed wire moving back and forth on the page, separating the panels into two separate images. The top two panels have a landscape view and a view of Angel Island behind a fence on the right and then information about the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act and the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act on the right. The next panel takes us into the interrogation, because that’s what it is, with the immigration official and immigrant on the right, and the barbed wired separating it from a comment about the year of these events, in 1936.

The fourth panel separates the official and the immigrant. The immigrant sits, in a smaller panel on the left, as the official, in a larger panel on the right, asks questions. The barbed wire separating the two moves to the far left, making the immigrant’s panel smaller. This positioning highlights both the gate that the narration mentions of the first page and the power dynamics at play, that the official, based on the immigrant’s answers, has the power to deny the immigrant entry. It also, with the overall use of the fence, highlights how both the official and the immigrant exist within a system that traps both of them, whether the official knows it or not.

These pages open The Good Asian, and they set the tone for what follows. In the next post, I will look at a few more pages and examine them in further detail. Until then, what are your thoughts? As always, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.