A few semesters back, I did a literature and composition course entitled “Who Watches Superheroes?” That course went really well, with students actively engaged in the texts and conversations surrounding them. This semester, I’m changing that course up a little, focusing specifically on Black Panther. This is something I have wanted to do for a while, but I have just never done it because I wasn’t sure exactly how to structure it since I can’t cover everything I would want to cover. While I really want to do a whole course on Christopher Priest’s run, I can’t do that in a literature and composition course. Since I can’t do that, I decided to focus on T’Challa’s debut in 1966, Don McGregor’s run in the 1970s, and the first part of Ta-Nehisi Coates’s 2016 run. Along with these runs, I am also toying with having students watch Ryan Coogler’s 2018 film. Since it is a literature and composition course, students will read scholarly works on each of these runs and the film, engaging with the scholars through response papers and research papers. I’m excited about this course, and I am really looking forward to see how it plays out. Below you will see the course description and the texts I plan to use.

Course Description:

In its opening week, Ryan Coogler’s 2018 film Black Panther surpassed its $200 million budget, ending its run by grossing over $700 million domestically and close to $650 million internationally, bringing its worldwide total to $1.3 billion. Coogler’s Black Panther served as a cultural touchpoint, and Chadwick Boseman’s portrayal of T’Challa inspired multitudes. What made the superhero film such a cultural touchpoint? It was important for a myriad of reasons, including the ways that it highlighted the importance of representation in media.

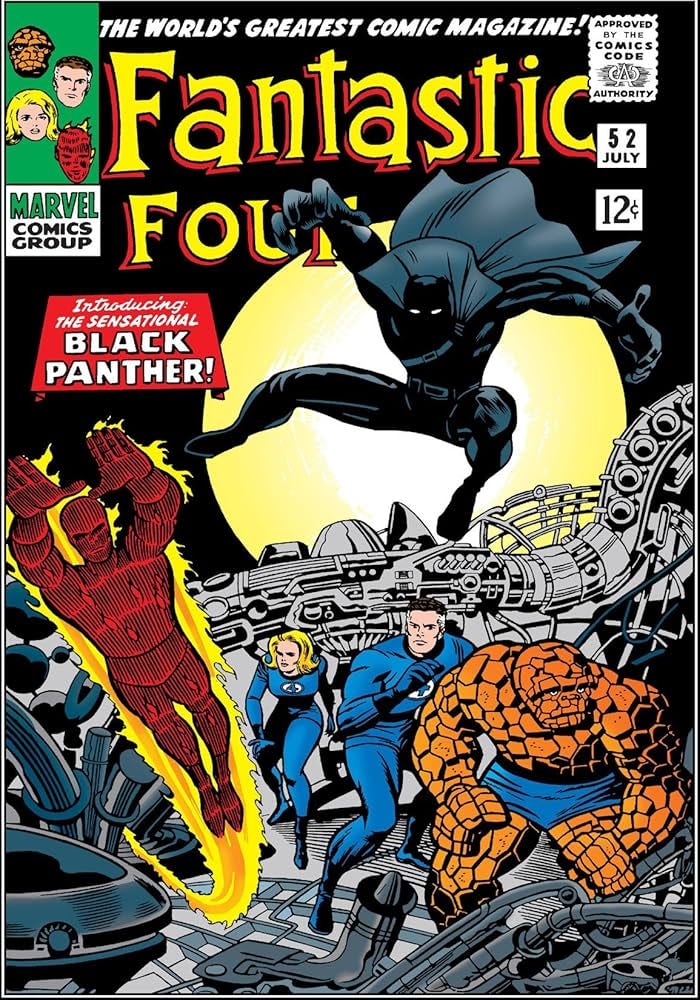

It took 52 years for T’Challa and Wakanda to reach the worldwide cultural level with the 2018 film. He debuted back in 1966 in Fantastic Four #52, to varied reactions. Some, such as Ken Grenne, praised his appearance. After praising Jack Kirby’s artwork, Greene wrote to the editors, “But the main thing that made my heart sing is the latest in your concerted effort to bring comic literature to a more adult level by portraying members of races other than white.” Others, though, such as Alan Finn, despised T’Challa. Finn wrote, “In your flood of letters praising F.F. #52, I thought some had better speak up for the minority of your readers. The Black Panther stinks!” Finn’s positions stemmed, partly, from the fact that T’Challa defeats the Fantastic Four, knocking them around like rag dolls.

T’Challa origin, as Qiana Whitted notes, speaks to the history of representation in comics and other media, but its is “also rooted in the social and political transformations that occurred in the United States and around the world in the mid-1960s.” Superheroes, by their very nature, appear larger than life, being able to do things that we, as “normal” humans could only imagine. Yet, they represent us, just as any literary character does, highlighting our strengths, our weaknesses, our insecurities, our fears, our joys. We identify with them because as the world explodes around us, they provide an escape and a way to protect us from the chaos, while commenting on it from the confines of a fictional universe grounded in reality.

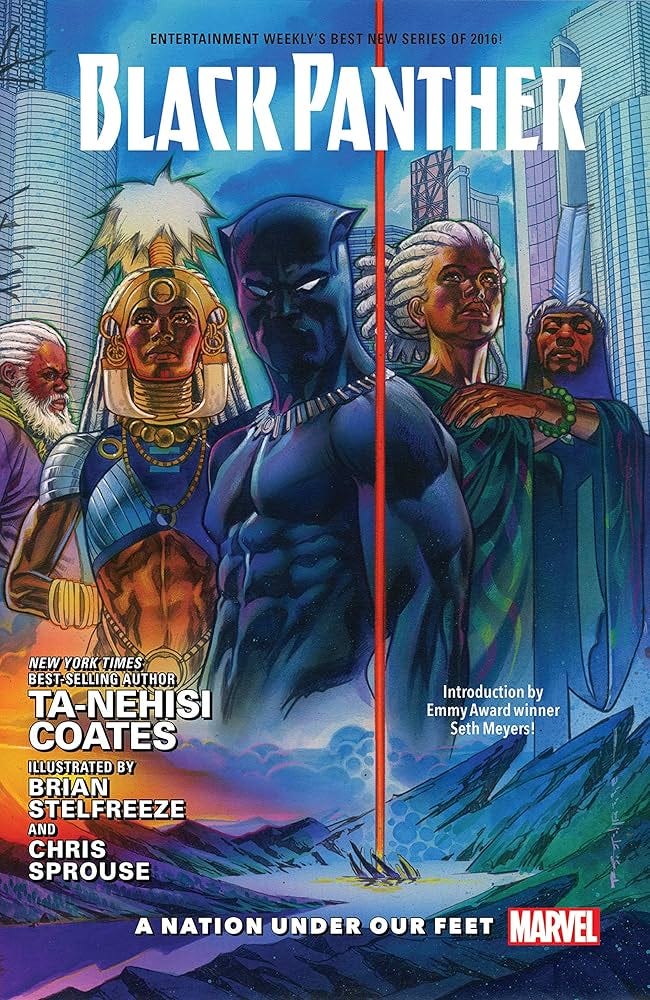

Writing about Ta-Nehisi Coates Black Panther: A Nation Under Our Feet, Killer Mike states, “The beauty of the comic book is that it lowers our defenses and provides an avenue for engagement in a way where the audience is likely to hear and then act. It is truth presented in digestible portions.” Comics democratize, bringing themes and topics to the masses, without the barriers separating individuals from accessing other mediums. They speak to the moment in which they appeared and engage with their audience in a manner that allows individuals to imbibe the message, ponder it, and then react to it. T’Challa, through his myriad appearances, does just that, from the 1960s to the present.

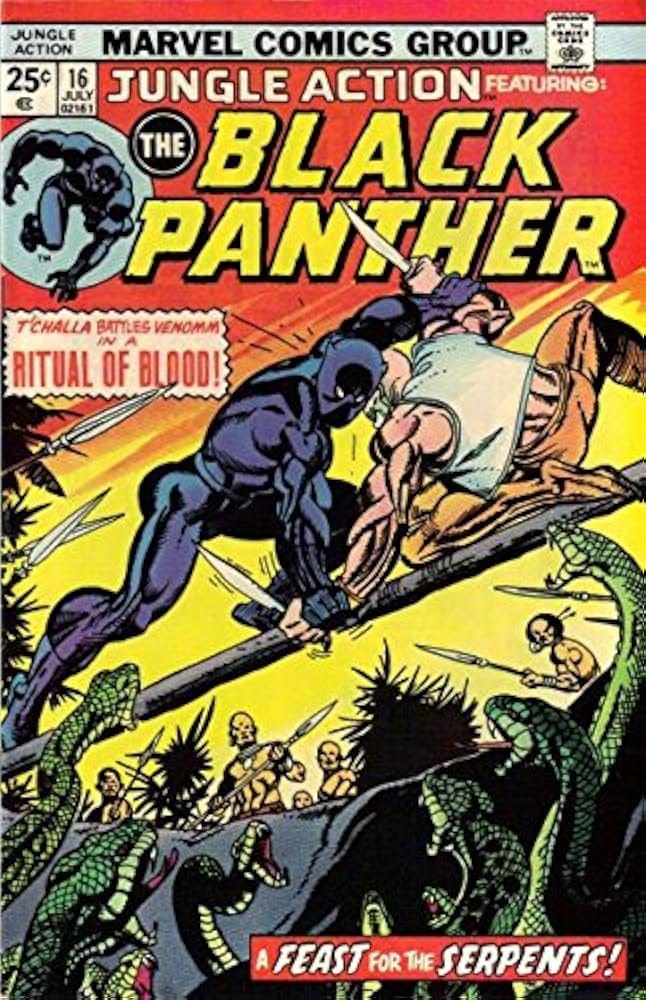

T’Challa, like any superhero, has changed over the years, depending on the writer, artist, and historical moment. Over the course of this semester, we will examine the ways that creators have, through T’Challa, commented on the past, their current historical moment, and much more. We will read Jack Kirby and Stan lee’s introduction of T’Challa in 1966 in relation to the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, and the history of representation within comics and culture itself. We will read Don McGregor and Billy Graham’s run in Jungle Action in relation to the economic issues of the 1970s and the post-Civil Rights era that also saw the celebration of the United States’ bicentennial in 1976. We will read Ta-Nehisi Coates and Brian Stelfreeze’s 2016–2017 A Nation Under Our Feet in relation to representation and specifically, as Coates puts it, the ways that representation reflects the world around us.

The importance of representation lies at the heart of T’Challa’s debut and legacy. While representation may not always be done well in his publication history, his mere appearance, in a cadre of white superheroes traipsing around urban environments like New York had an impact. Even while some like Alan Finn disparaged T’Challa’s introduction, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee saw T’Challa’s debut as an important moment. Replying readers like Finn, they wrote, As Stan Lee and Jack Kirby point out in their response to a reader after T’Challa’s debut in 1966, “Perhaps a comic mag isn’t the proper place for this type of discussion — and yet, there’s a chance that these pages, which are widely perused by thinking readers throughout the world, are possibly one of the best places of all! ‘Nuff said!”

This course focuses on literature and composition, specifically on critically analyzing literature, reflecting on it, and conducting research to help you engage in scholarly discussions about the literature you read. With this in mind, we read T’Challa’s debut, “Panther’s Rage,” “The Panther versus the Klan,” and “A Nation Under our Feet”; we will also view Ryan Coogler’s 2018 Black Panther. Along with these story arcs and the film, we will engage with scholarly research on Black Panther, reading and responding to various academic articles that explore various themes contained within the texts that we encounter. You will respond to this scholarship and use it to craft your own arguments about the story arcs we read or the film.

Primary Texts:

Coates, Ta-Nehisi, Brian Stelfreeze, and Chris Sprouse. Black Panther: A Nation Under Our Feet. Penguin Books, 2025.

Coogler, Ryan, director. Black Panther. Marvel Studios, 2018.

McGregor, Don, Rich Buckler, Billy Graham, Stan Lee, and Jack Kirby. Black Panther. Penguin Books, 2022.

Secondary Texts:

Chambliss, Julian. “‘A Different Nation’: Continuing a Legacy of Decolonization in Black Panther.” The Ages of the Black Panther: Essays on the King of Wakanda in Comic Books, edited by Joseph J. Darowski, McFarland, 2020, pp. 204–219.

Leogrande, Cathy. “Breaking (Some) Ground While Dodging Politics: How Stan Lee and Jack Kirby Started a Legend.” The Ages of the Black Panther: Essays on the King of Wakanda in Comic Books, edited by Joseph J. Darowski, McFarland, 2020, pp. 20–35.

Lund, Martin. “‘Introducing the Sensational Black Panther!’ Fantastic Four #54–53, the Cold War, and Marvel’s Imagined Africa.” The Comics Grid, vol. 6, no. 1, 2016.

Peppard, Anna. “‘A cross burning darkly, blackening the night’: Reading Racialized Spectacles of Conflict and Bondage in Marvel’s Early Black Panther Comics.” Studies in Comics, vol. 9, no. 1, 2018, pp. 59–85.

Teutsch, Matthew. “Black Panther, Surveillance, and Racial Profiling.” Black Perspectives, African American Intellectual Historical Society, 10 March 2018.

Wanzo, Rebecca. “Resisting the Revolutionary Call.” New Political Science, vol. 44, no. 3 (2022), pp. 450–456.