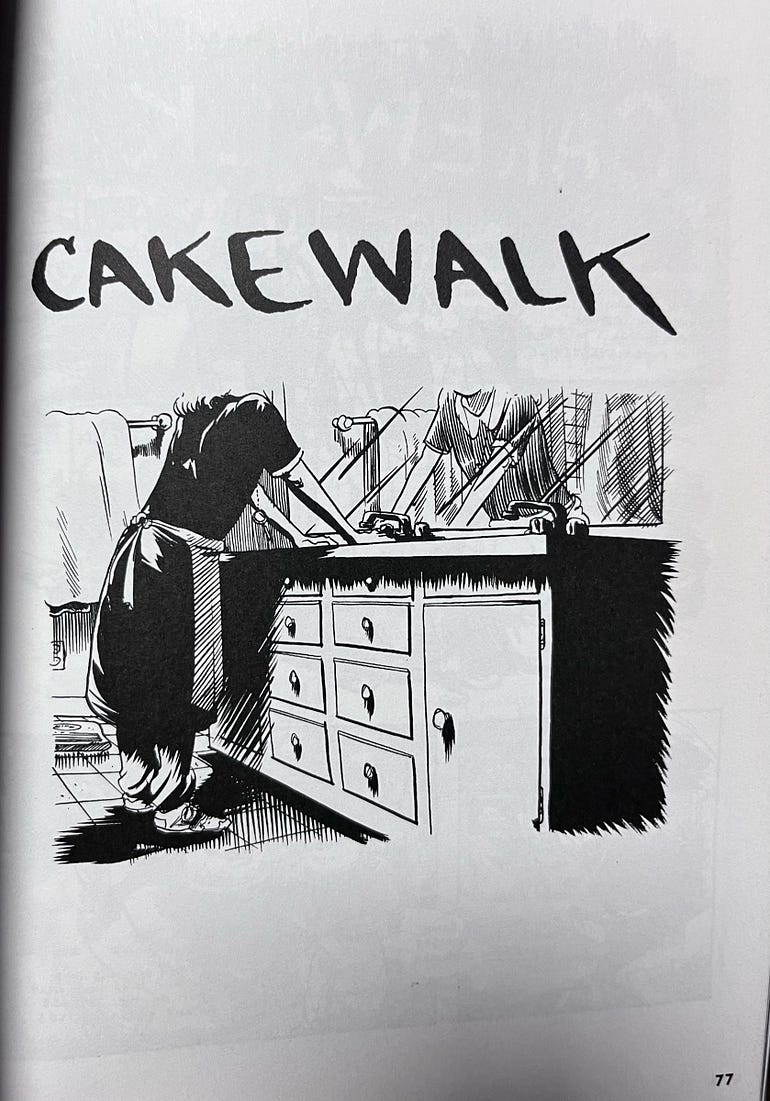

When I teach first year composition, I usually frame the course around personal narratives, allowing students to write about themselves. I find that this helps them get comfortable with writing and allows them to express themselves through their essays. As such, I try to choose at least one text that contains personal stories. This semester, I decided to add Nate Powell’s You Don’t Say, a collection of Powell’s short stories between 2004–2013. I chose Powell’s collection because it is a mixture of stories that explore his own identity as well as broader existential questions about the world we inhabit. On choosing You Don’t Say, I knew that we would have important conversations, specifically when we read “Cakewalk.”

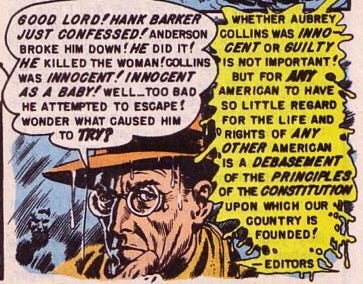

In the lead up to reading Powell’s You Don’t Say, we read EC Comics’ Shock SuspenStories volume 1. Each issue in that volume contains what the editors at EC called “preachies,” stories which conveyed a direct moral message and called out racism, antisemitism, xenophobia, and more. After reading, some students said that stories such as Al Feldstein and Wally Wood’s “The Guilty!”, which deals with a Black man being falsely accused of a crime against a white woman and being lynched, was “racist.” This assertion stuck with me, partly because the story explicitly calls out, as do the other “preachies,” white supremacy and racism. At the end of “The Guilty!”, the narrator proclaims the message clearly, saying that it didn’t matter if Aubrey Collins was, in fact, guilty of not. What mattered was that he did not receive due process under the law. Now, we could argue whether or not the message is forceful enough since the perpetrators get away with killing Collins, but can we call it “racist?”

The students’ argument about “The Guilty!” being “racist” stuck with me, and when we got to “Cakewalk,” I wondered what they would think. To help them hone their critical reading skills, I asked them to write about the following question, “Is Nate Powell’s ‘Cakewalk’ racist?” This question specifically asked about the story itself, so the overall message that Powell seeks to convey with “Cakewalk.” It does not ask about the characters or their actions, and this aspect, thinking about characters, actions, and dialogue, is where I think some of the students thought that “The Guilty!” and other stories are “racist.” I wanted them to examine, first the word “racism” and what it means and then apply that definition to Powell’s intentions with the story.

Within the question, I provided students with a link to the Oxford English Dictionary’s (OED) definition of “racism.” The OED defines “racism” as a “[p]rejudice, antagonism, or discrimination” enacted upon individuals based on their nationality, ethnicity, or race. These attacks can come from individuals themselves, institutions, or society as a whole. Along with this, it includes the belief that, based on certain characteristics, one group of individuals is “superior to others.” With this definition in mind, students thought about whether or not Powell’s “Cakewalk” fits the definition of “racism.”

Powell prefaces “Cakewalk” by writing that “[i]t’s a true account of [his wife] Rachel’s life growing up in the homogenous culture-bubble of Northwestern Indiana, of adults failing young people at every opportunity to provide direction.” He also admits that it was his “second-favorite story” that he had worked on. One must keep Powell’s statement, specifically his comment about the community and adults failing Rachel, when reading “Cakewalk.” The story focuses on Sara, a young girl who decides to go to school dressed up as Aunt Jemima for Halloween. To complete the costume, she even blackens her face with charcoal. This act of participating in the historically racist practice of blackface could lead one to view the story, from the outset, as “racist” because it depicts Sara engaging in a racist act.

However, the story immediately jams a wrench in that line of thought when Sara encounters her classmates at the bus stop. A boy looks at her, asks her who she’s supposed to be, and when Sara tells him, the boy asks the other kids around him, “Can you believe that Sara is going as a n***** for Halloween?” Sara doesn’t understand why the boy said that because she sees her costume as appreciative of Aunt Jemima, as a form of reverence. She doesn’t understand why someone would proclaim that she “is going as a n***** for Halloween.”

When the bus arrives, Sara gets on, and the bus driver, Mr. Creepmurr, who never said anything to her, tells her, “Hey, they didn’t tell me I was stopping in Gary today!” Again, Sara doesn’t understand the comment, so she uncomfortably laughs at Mr. Creepmurr’s comment and thinks back to her parents and a trip they all to the Brookfield Zoo, a trip where they drove throuh Gary, Indiana. Sara recalls, “i remember it was the only time mom and dad ever made me lock my door while we inside the car. i saw a lot of people standing in front of crummy old buildings with bright lines of paint zig-zagged all over them. they told me it used to be nicer back when they were in school.”

Sara doesn’t realize that Mr. Creepmurr’s comment is, in fact, “racist” because he sees Sara in blackface and makes a prejudiced comment about Black citizens in Gary. This causes Sara to think about her own experiences in Gary, but she doesn’t draw the connection between Mr. Creepmurr’s “racist” comment and her parents’ “racist” comments when they tell her to lock the doors and how much better Gary was when they went to school there. Sara’s parents convey “racism” by essentially saying that Gary, now, is dangerous because of the Black population and it was better before the demographic shift.

Before she even goes to school, Sara’s dad laughs at her when she tells him who she is dressing as for Halloween. We don’t see her father, but reflecting back on the scene, Sara tells us that “he laughed” and told her that she “couldn’t do that,” not because of the appropriation and racist stereotype of Aunt Jemima but because Sara is white and Aunt Jemima is Black. This comment causes Sara to use charcoal to blacken her face, and no one says anything about her decision. It’s not till she gets to school that someone tells her to wash off the charcoal.

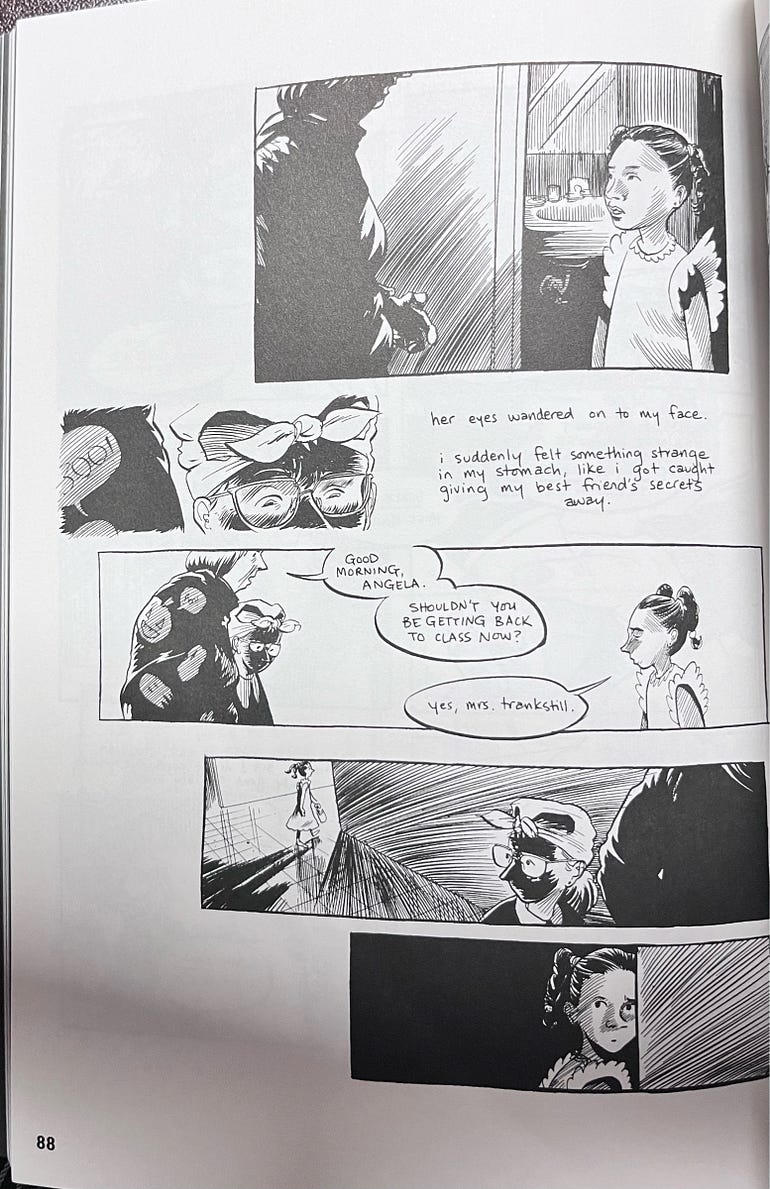

At school, Sara’s teacher Mrs. Trankstill sees her and tells Sara to come with her to the bathroom. Like the other adults, Mrs. Trankstill deson’t tell Sara why her costume is “racist.” She only tells Sara to come with her, and she drags Sara to the restroom as Sara pleads that its only her costume. Mrs. Trankstill asks, “Aunt Jemima — my goodness, what in the world were you thinking? Why would you want to do that to your face?” Sara innocently asks back, “What’s the big deal anyway? Why can’t I be her?” Again, Mrs. Trankstill doesn’t answer; instead, she continues to pull Sara towards the restroom.

When they reach the bathroom, Angela, a Black student, comes out of the door and looks at Sara. This is the only really moment where Sara feels any sense of why her choice of costume is wrong. Angela looks at Sara, and Sara says, “”her eyes wandered on to my face. i suddenly felt something strange in my stomach, like i got caught giving my best friend’s secrets away.” Sara feels, in this moment, a tinge or remorse and guilt. She can’t explain it, but it’s there, in Angela’s gaze. The sequence concludes with Sara and Angela looking at each other as they walk away. Yet, Mrs. Trankstill continues to pull Sara into the restroom to wash off her face, not even commenting on the problem.

“Cakewalk” contains racist characters and actions. We see that with the boy at the bus stop, with Mr. Creepmurr, and with Sara’s choice of costume. However, the story is not “racist.” Its main critique involves the lack of conversations surrounding race, specifically within white communities. No adult tells Sara the history of blackface or even the steroetypes behind Aunt Jemima. Sara sees Aunt Jemima staring at her every morning from the syurp bottle and envisions her stirring a pot and making the floorboards creek as she walks and cooks for her family. She doesn’t see Aunt Jemima with the context of the “mammy” steroetype. She doesn’t know that history, and if the adults around her know it, they don’t say anything.

By asking students whether or not “Cakewalk” is a “racist” story, I wanted them to think critically about the text, to move beyond our initial reactions that may cause us to view something in one way when in fact it is counter to that way. I wanted them to understand the ways that we need to engage with media, parsing it out and looking for the meaning, not what may or may not offend us. I also asked them to think about audience. “Cakewalk” has a specific audience, white individuals, either adults or kids, who refuse to engage with discussion of race and racism. That aspect, as well, must be kept in mind because it informs the choices in the story and how Powell presents it.

There is more I can write, but I will leave it there for now. What are your thoughts? As usual, let me know in the comments below. Make sure to follow me on Bluesky @silaslapham.bsky.social.